As Access2Arts's access and inclusion coordinator, Meg Riley trains people in the skill of audio-describing visual art – a practice she says is necessary to make art accessible to all.

The art of painting pictures with a thousand words

Meg Riley has a history of finding new ways for Adelaide audiences to experience arts and culture.

She was the South Australian Museum’s community programs coordinator from 2016 to 2022, and in 2019, under the guidance of Lara Torr, she helped the institution develop a series of sensory-friendly experiences.

These were ticketed events, during which the museum staff turned down the lights and volume within the building, rolled out beanbags, and handed out sensory maps to visitors.

If you are blind or vision impaired and want to participate in a Nexus Arts Gallery audio-describing tour, contact the gallery via their website for more information.

If you want to find out more about all the accessible and inclusive art experiences in Adelaide, visit the Access2Arts website for more information.

The aim was to make the museum accessible for everyone, especially people with autism. The feedback after the event from the neurodivergent participants — spanning kids to young adults — was astounding.

“We got things, like, ‘We would never have been able to visit without this’, ‘We’ve had terrible experiences before and this gave us an amazing memory’,” Meg tells CityMag.

“We’re always looking to get more people into museums or galleries.”

Since 2019, Meg has done myriad other things, such as setting up SA Museum’s first podcast and completing an Icelandic visual arts residency. Most recently, she landed the important job of coordinating Access2Arts’ audio description program as the organisation’s access and inclusion coordinator.

Audio description is commentary for people who are blind or have a vision impairment. Trained describers offer live verbal commentary of a work in an art gallery or theatre.

“Usually… in the theatre, and I’d be up in a little box at the back with a microphone, and a blind or visually impaired audience member would be sitting in the audience with a headset, and I would be adding some visual info in between the dialogue to say, ‘A woman in a red dress walks in’ or ‘He holds out a knife’,” Meg says.

The last theatre piece Meg provided commentary for was End of the Rainbow by the South Australian State Theatre Company in 2019. For theatre, she characterises the job as a test of speed.

“You have to get [the description] in between dialogue,” she says. “You have to get the short little clip in the most efficient way possible but when you get it right, it’s like slicing hot butter, scissors through wrapping paper.”

Meg Riley says Nexus Arts has inclusivity built into its core

Meg completed six weeks of audio-description training in 2016, learning from visually-impaired trainer Jody Holdback. We’re speaking with her today inside a gallery at Nexus Arts, where she’s developing audio-described tours for visual art exhibitions.

Adelaide nightlife generally is littered with accessibility problems, and the city’s cultural institutions are not exempt.

“At the outset, galleries and museums are not very accessible for disabled people and we’re often left out,” says Meg, who has lived experience of disability.

“But there are lots of people doing a lot of work above and beyond their jobs to make sure that things are a little bit more accessible.”

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 18 per cent of Australians live with disability, which means cultural institutions that are not accessible risk turning away almost one in five people within their community.

It’s Meg Riley’s job to make art accessible for all

“We are everywhere,” Meg says.

“And the feedback that we get from participants [with disability] who get involved with museums and galleries is overall extremely positive.”

Nexus Arts ran its first audio-described tour last year, with Meg providing “important visual information” about the exhibition’s artwork. For the Nexus tours, audio describers comment on the artwork in a “linear, systematic way” and express the “intent and emotion” of certain pieces.

When speaking about the emotion of an artwork, Meg says it’s important to justify the experiential description.

“If I say someone’s looking sad, I would never just be, like, ‘She has a sad expression on her face’,” Meg says.

“I would say ‘Her eyes are turned down, with [sadness]’.

“You’re meant to provide the visual information that sighted people would get.”

Despite the positive reception from participants, Meg says not everyone in the arts community sees services like audio description as necessary.

“I have previously had a lot of challenges with sometimes getting other people on board with the idea that access is worth contributing to,” Meg explains.

“But millions of people in Australia are disabled. It’s a whole demographic of people that we’re not providing for.”

‘Find That Pace’ by Shirley Jianzhen Wu

Find That Pace

Open now, until 17 March

Nexus Arts

Lion Arts Centre, North Terrace, Adelaide 5000

More info

To illustrate the process of an audio-described tour, Meg leads us through Nexus’ current exhibition, Find That Pace by Shirley Jianzhen Wu. The artist’s statement describes this as a collection of work centring on the contradictions of belonging to place(s) for migrants.

Meg starts her tours reading a short pre-prepared script or the exhibition description from the gallery wall. Next, she describes the room itself, commenting from the outside in.

“I’d say this exhibition is in the Nexus Arts Gallery, which is a rectangular workspace around six metres by eight metres, with a permanent white column in the middle,” she says.

From here, she begins describing the art within the room.

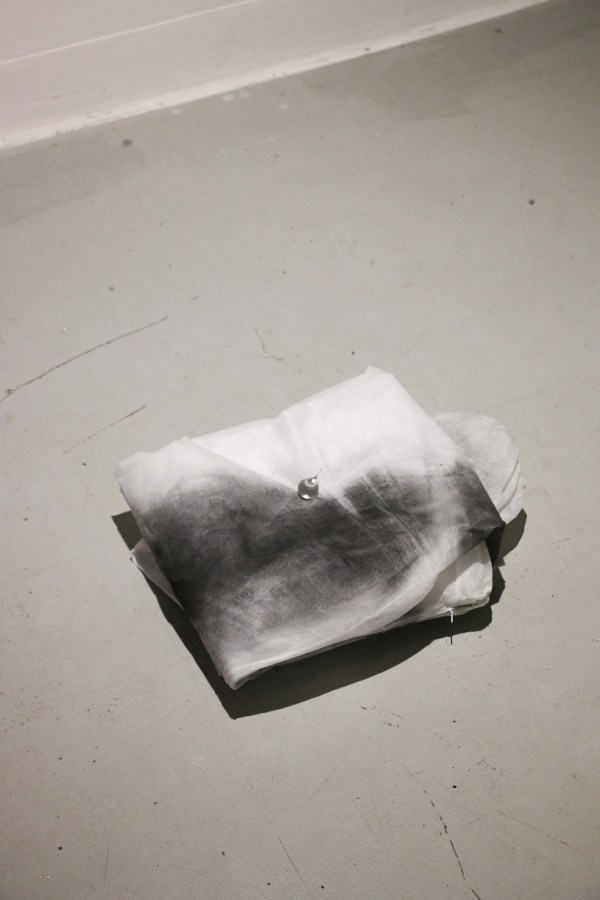

“Shirley’s exhibition is incredibly sparse, so all of the walls are white, and if we’re walking, the grey floor is empty, except for four deliberately placed piles of white clothing smattered with charcoal, and along the right-hand side, one long strip of paper that extends down the whole length of the wall,” Meg says.

Because this exhibition consists of only a few works, Meg says she can spend more time on each piece and describe them in thorough detail.

She systematically combs through each of the six artworks in this gallery, starting off with the 30-centimetre by 40-centimetre rectangle piles of white hazmat suits sitting to our left. She repeats this process throughout the room until she’s described everything in the gallery.

‘Chewing gum melting under the sun’ (2023) by Shirley Jianzhen Wu at Nexus Arts Gallery

Much like the feedback from participants attending the South Australian Museum’s sensory-friendly experiences, Meg says the audio-described tours often end with a heart-warming interaction between her and the gallery visitor.

As we leave Nexus, waving goodbye to Meg, we notice anew the ramp that connects the gallery to the University of South Australia forecourt.

We recall something Meg said earlier, about ramps allowing every kind of person to enter institutions.

Notions of inclusion and accessibility often bring to mind these forms of physical infrastructure that help people access a building. We walk away with a new sense of accessibility also being about bringing new audiences into the art itself.