In part one of CityMag's guide to the economy, we seek to establish where money comes from and quickly discover it starts with dirt. Join our founder, Josh Fanning, and the University of Adelaide's Dean of Business, Noel Lindsay, as they traipse across SA to track how the economy works.

What even is the economy? A three-part series on how SA makes money and stuff

South Australians have perhaps never been quite so aware of the economy as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Panic buying swept our supermarkets, Australia officially entered its first recession in 28 years, and many of us are receiving JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments designed to keep just enough money in the system to stop the whole show falling apart.

What Even is the Economy? is a three part series of articles produced by CityMag and The University of Adelaide, and published in words and pictures across citymag.com.au and Instagram.

Read on below and watch interviews recorded live on our Instagram Story here.

This is part one in the series. Read part two and part three.

Even before the coronavirus-induced toilet paper hoarding took effect, the concept of ‘the economy’ has had a power over us since Bill Clinton’s strategist James Carville made that famous quip in 1992: “It’s the economy stupid.”

But what even is the economy?

What is this mysterious creature that both moves us to behave in peculiar ways (cue toilet paper hoarding), but is itself affected to a large degree by our emotional state of mind (ie: consumer and business ‘confidence’).

Unable to come up with a satisfying answer on our own, CityMag turned to the University of Adelaide’s Business School, which has for more than 140 years been at the forefront of business education, delivering innovative and transformative degrees and creating a network of alumni with real-world influence in the business community.

The University of Adelaide’s Dean of Business, Professor Noel Lindsay, an academic with real-world experience founding successful businesses, agreed to lead us on a three-part road trip across the South Australian economy.

BUT FIRST, BAKED GOODS

The country town bakery is a standard indicator of the health of the local economy. Pictured: Meadows Bakery

In this first instalment, we pile into Josh’s VX Holden Commodore (a car which was once manufactured down the road in Elizabeth) and head for the South Eastern Freeway, en route to the nearby agricultural regions of the Adelaide Hills.

Observing Noel and Josh from the back seat as they exchange life stories, the two, at first, seem worlds apart.

Noel is middle-aged, a Chartered Accountant turned academic. He’s part of the University’s senior leadership as Pro Vice Chancellor Entrepreneurship, and Dean of the Adelaide Business School. Prior to academia Noel spent his life establishing ventures in Australia, South Africa and Malaysia. He was part of one of Australia’s oldest venture capital firms, and is dedicated to demonstrating how education and an entrepreneurial mindset can create value for communities.

Josh is in his thirties, the founder of a culture-orientated street magazine (the one you’re reading now) and now Group Creative Director at KWP!, and is best defined as an all-round creative type.

As we eat pasties and drink coffee at Meadow’s Bakery, conversation turns to the economy and the pair quickly find common ground.

“I’m a capitalist, but I also believe in the importance of education and of the need to help the disadvantaged,” says Noel.

Josh nods in agreement, “What’s the point of capitalism if it’s not to make the world a better place?”

MONEY DOES GROW ON (OR FROM) TREES

Surrounded by wealth in Kuitpo Forest, Josh Fanning reckons our parents lied to us when they said, ‘money doesn’t grow on trees’

We’re in Meadows because Josh wants to take Noel to Kuitpo Forest. Kuitpo is the first plantation forest planted by the South Australian Government and has been sustainably growing and harvesting timber since 1898.

“Money doesn’t grow on trees,” says Josh, as we walk across pine needles amid the majestic forest of pinus radiata.

“That’s a thing parents say to their kids when the kids are asking for a new Nintendo. But actually, here – in the middle of this pine plantation that grows and harvests trees to turn into lumber that is then sold and turned into money – aren’t these trees actually where money comes from?”

“Well you’re right,” says Noel.

“When settlers first came here they had to focus on agriculture to feed themselves, and of course timber was important for building houses.”

“You’ve got to grow food, first of all to feed yourself, but then if you want to develop, you’ve got to grow enough food to sell it.”

“In essence, economies are about trading things of value, whether that’s goods, something we make; or services, something we provide.

“But there’s got to be some form of exchange, and in modern economies we refer to that as finance.”

THREE ESSENTIALS TO EVERY ECONOMY

Noel explains that for an economy to grow, money is important, and there’s three other essential components to that.

“First of all there’s trust,” he says, “trust in the currency, in the medium of exchange, that if I go somewhere else and use whatever the currency is, someone will agree that it’s worth something.

“Credit is also really important, and part of extending that credit is that you expect to grow what you are doing. So if you want to borrow money to set up a business, I may be interested in loaning you money or investing in you because I can see a future for you. So we have to believe in tomorrow.

“And entrepreneurship is core to any economy, because it’s about creating markets – someone selling something, someone buying something. Entrepreneurship is future orientated – these are people who can visualise the future.

“What you’ve described is a sort of tension there between reality and the economy,” says Josh.

“The economy is about trust, it’s about believing in the future, believing the vision of entrepreneurs, that they can see the value of our future – I’ve never really thought about that, that the economy is so… mythical.”

An entrepreneur’s actions, though, are always applicable to the real world.

“An entrepreneurial mindset is a ‘can-do’ mindset. It’s about being positive, being purposeful. Being visionary, and innovative. Resourceful, resilient and adaptive,” he says.

“Entrepreneurs are stimulated by change, by challenge. They are creative problem solvers. Entrepreneurs step towards big problems, and creatively identify the solutions. That mindset is valuable to small start-up businesses, to non-profits, and to large scale, multinational companies.”

HOW TO ADD VALUE TO A PRODUCT

We jump back in the Holden and head up the road to some Kuitpo vineyards, where we meet a family of entrepreneurs combining traditional agricultural practices with modern research and methods.

The question Josh has for Noel, and for the winemakers we’re going to meet, is simple, “How do they make money out of dirt?”

It’s a deliberately provocative take on the French concept of terroir, but is in keeping with the newfound knowledge that money does indeed have something to do with trees.

Neil Jericho wasn’t so sure that he was making money out of dirt.

Andrew Jericho is head winemaker and is currently indulging his curiosity around the cultivation of mushrooms and microbiology

Stunning country just west of Kuitpo Forest

Neil and Kaye Jericho and their children Sally, Andrew and Kim are the team behind Jericho Family Wines.

Dad Neil has more than three decade’s experience making wine for some of Australia’s best-known wine brands. Through Jericho he combines that winemaking pedigree with son Andrew’s flair for new approaches to the practice.

“I did the oenology course at the University of Adelaide and it was great. I’m even thinking about going back,” says Andrew.

“I’ve got a big interest in microbiology. I’m looking into using isolated wild strains (of yeast) from forests around the world and culturing them up to see if there’s a more complex array of microbes that we can utilise.”

It’s only a small step from pine trees to grape vines, in that they are both bark-covered organisms with leaves that grow in the dirt.

However, it’s a giant leap in economic complexity between grapes and timber. Wine is one of the few industries where we add value to a natural resource and develop it into a finished product here in South Australia and export it around the world.

It’s important to understand how we take this natural product and build a business out of it.

After paying growers, and pickers, and purchasing bottles, and labels, investing in design, and paying for your wine to be shipped around the state and country, there’s not a whole lot of money left for Jericho Wines, explains Sally, the company’s accountant.

Neil, her father, smiles. “There’s a saying in our business: the only way to make a small fortune in wine is to start with a big one.”

But the Jerichos see their place in the economy as long-term, sustainable and extending into the next generation. One of the values Neil sees in his business is its “history” – which we love as an economic measure.

Our final stop is the University of Adelaide’s Waite campus, home to the largest concentration of agriculture and wine research and teaching expertise in the Southern Hemisphere.

It is the campus where Andrew Jericho – and most other winemakers in South Australia (and across the country) – learnt the science behind crushing grapes.

L-R: Andrew (winemaker) Neil (winemaker), Kim (graphic design and marketing), Sally (accountant) of Jericho Family Wines

A LAB FOR EVERYONE

Head Winemaker Paul Grbin and Scholarly Teaching Fellow and Assistant Winemaker Jill Bauer

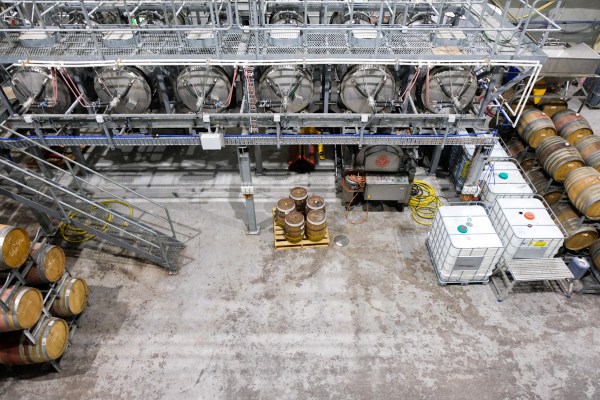

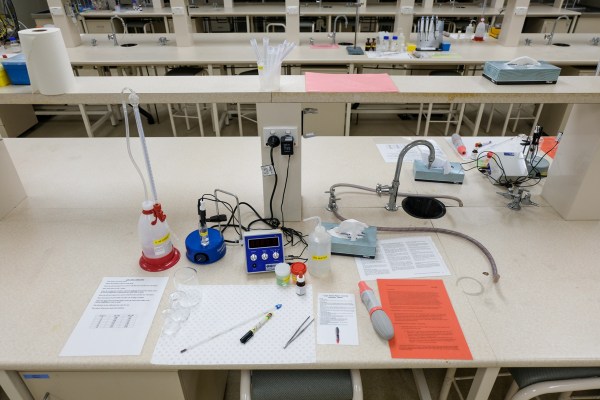

Not your average classroom. Waite creates up to 70 per cent of Australia’s winemaking graduates

We meet Associate Professor and Head Winemaker Paul Grbin and Scholarly Teaching Fellow and Assistant Winemaker Jill Bauer on a platform overlooking the University of Adelaide’s Hickinbotham Roseworthy Wine Science Laboratory.

This is the largest teaching winery in Australia and Paul estimates that as many as 70 per cent of winemakers working in Australia were trained in this facility.

We kick things off by asking Paul, one of the state’s foremost technical wine experts, what makes good wine.

He offers a refreshingly untechnical response: “What’s good wine is what people are prepared to drink.”

“If they are happy with it and it serves a purpose, and that might be to have a glass of wine when they get home from work because they’ve had a hard day, or it might be to celebrate a special event… It comes down to whatever they like.”

Jill agrees, and says that it’s the diversity within wine that makes the industry beautiful.

“If there wasn’t a rainbow of flavours out there to appeal to a wide range of tastes, then we wouldn’t have an industry, or certainly not one that’s as interesting as this one is,” Jill says.

“I think the Australian industry is positioned to take off, again, on a premium level, on a quality level, on a uniqueness level [because] so many of our brands are really hand-made, but we don’t have to pay Napa Valley prices for fruit.”

This exemplifies the economy as we are now coming to understand it: items only have value if regular people are prepared to become customers by parting with their money to purchase a product.

The ability to create this metamorphosis is happening at great scale in the primary industries and agribusiness sector, which contributes more than $15 billion to South Australia’s gross state product.

Many winemaking students at the University of Adelaide’s Waite campus aspire to go on to run their own wine businesses, and cut out for themselves a slice of that $15 billion pie.

What you eat and drink (consume) has a whole lot of science behind it and before it gets near your mouth

The Waite campus doesn’t just turn out graduates; it also keeps in touch with the wine industry. So much so, Jill and Paul deployed winemaker students to those Adelaide Hills wineries affected by the 2019-20 summer bushfires to help clean up and rebuild.

“In some cases those wineries were graduates of the program, in other cases they were friends of ours,” says Jill.

“David Bowley of Vinteloper,” says Paul. “He lost a great deal in those fires, but we made his first ever wine here at Waite.”

Josh is taken aback by this real-world integration between a primary industry and the university, but Noel makes sense of it quickly.

“You can’t talk about the economy without talking about innovation and entrepreneurialism,” he says.

“There’s a very strong link between an ‘entrepreneurial mindset’ and better performing economies and better performing businesses.”

We’re reminded of what Noel said earlier: “Entrepreneurs are problem solvers. They are stimulated by change, by challenge.”

An entrepreneurial thinker steps towards problems like those created by the fires.

Driven to innovate, to identify and create the solutions to support businesses through disruption, they will look for ways to create new opportunities for growth, ultimately supporting a healthy and resilient economy.

In part two of our journey into the South Australian economy, Josh and Noel take a trip out to a suburban mine to talk about the value to the economy of blasting rocks out of the ground and how hydrogen could transform South Australia’s future if we smarten up our mining industry.