Blasting rocks out of the ground still has monetary value in 2020. Step inside the South Australian economy and visit a suburban mine to learn a thing or two about how hydrogen has the power to transform our state's future - if we smarten up our mining industry.

The elemental economy: Rocks and hydrogen

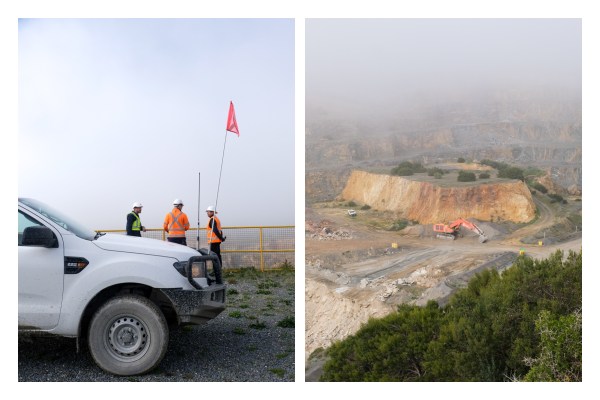

There’s a blanket of fog lying over Adelaide, as CityMag sets out to make the second instalment of this series on the South Australian economy.

What Even is the Economy? is a three part series of articles produced by CityMag and The University of Adelaide, published in words and pictures across citymag.com.au and Instagram.

Read on below and watch interviews recorded live on our Instagram Story here.

This is part two in the series. Go back and read part one, or go on to read part three.

The heavy, low-lying cloud, through which it’s hard to see further than 20m, provides a neat metaphor.

Like the fog, conversations about the economy are frustratingly opaque.

Talk of mysterious market forces and -isms – from capitalism to neoliberalism – characterise economic rhetoric. But as our local economic guides, CityMag co-founder Josh Fanning and Dean of Business at the University of Adelaide Professor Noel Lindsay, arrive at Boral’s Linwood Quarry in Seacliff Park, things seem deceptively simple.

“This site here opened in 1885, so it’s been around for a while,” says Scott Retallick, the quarry’s manager. “And the aim of the game is you get a rock out and you make it into a smaller rock.”

These stones – like the trees we saw at Kuitpo Forest in episode one – have long provided a foundation for the South Australian economy.

“Quarrying is not new to humanity – you only have to go back and look at the Egyptians to see how far back it goes,” says Noel.

“We’re so advanced these days, but we still use fundamental things. We dig up rock, crush it up, and then use it for a whole variety of things – including asphalt roads and building materials. They’re things that still have real value.”

To go on site at the Boral quarry click here to view our Story on Instagram.

Scott was being modest in his assessment of the quarry’s operations. While the product remains similar to 135 years ago, the process of mining the stone has changed dramatically. The key motivator for the most recent changes has been the needs of those living near the quarry.

Top: The weigh bridge; Above: Where rocks are turned into money – the quarry’s major crushing plant.

“Our business is built on honesty and trust with the residents,” says Scott. “We’re always trying to set a new bar and trialling new things in the industry for managing the effects of things like blasting and dust.

“We’ve done lots of things that are very progressive – we have real-time dust monitors and I’ve introduced a couple of new initiatives, including fog canons. We spend a lot of time communicating with our neighbours too, because transparency is key.”

Scott Retallick

Josh quickly sees a lesson here about how the economy and society are linked, rather than separate, systems.

“It’s that tension in the economy that I’m interested in – that we have to take some responsibility as a society for what we’re doing,” he says.

Noel agrees – pointing out that social pressures and people power are becoming as influential as more abstract market forces.

“These days there is more of a focus on sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability,” he says. “If you want to have a business that is going to last… you have to give something back to the community.

“So – even with quarries… they say they’re interested in extracting minerals out of the ground, but they also want to restore when they’re finished and leave it in a better state. If they weren’t doing that, I think you would have a lot of people saying they don’t want the quarry here.”

We drive along the coast toward a pub lunch and our next appointment – a Zoom meeting with Dr Chris Matthews from the University of Adelaide’s Institute for Mineral and Energy Resources (IMER).

IMER operates at the forefront of the international mineral, energy and resource sectors. The institute has more than 250 staff and postgraduate students, some of whom work with government or in business partnerships relating to fundamental and applied research.

As we head toward Brighton, we’re more aware of the roadworks, apartment developments, and coastal reinforcements we’re passing – many of which likely use stone and concrete produced in the Linwood Quarry.

In the driver’s seat, Josh has moved on from the classical problem of how the economy and society interrelate and is instead puzzling over a more modern issue.

“During the early weeks of the COVID-19 shutdown, I saw a tweet from BHP saying they were creating an extra 1,500 jobs,” he says.

“And of course, there were thousands of angry replies saying that we shouldn’t be expanding mining in Australia, that we need to shut it down.

“But, mining is not just coal. To build renewable energy technology like solar panels and batteries we need to mine rare earth materials.”

To watch the interview with Dr Chris Matthews, click here to view our Story on Instagram

Noel agrees – mining is a part of our future, he says, but we’re going to need innovation to ensure that mining adapts to a world that requires different products and that puts environmental concerns first.

As we discussed with Noel in part one of this series, this is where the “can-do mindset” of entrepreneurial thinking takes a critical role, bringing forth new and innovative ideas.

On Zoom, Chris Matthews enthusiastically describes how this is playing out in SA.

Chris’ job at IMER involves bringing together industry and academics to create a brighter resources future. He sees huge potential – from participation in global movements like swapping out diesel fuels for electrification on mining sites, to SA-specific opportunities like combining our abundant iron ore with new technologies that harness the power of hydrogen.

“Hydrogen can do everything that coal can do. The issue with hydrogen is there’s almost no naturally occurring hydrogen in the world,” says Chris.

Dr Chris Matthews

“But if you can split water, you can have the hydrogen and you don’t have the carbon dioxide emission. Right now, the method is to zap it with electricity – and that’s why South Australia and Tasmania have got this advantage, because we have way more renewable electricity than we can use.

“We’re talking about exporting our hydrogen… there’s a few issues, hydrogen is not a very happy molecule, it doesn’t compress very easily. So, what the Grattan Institute has said recently is that rather than export hydrogen, we should use it to make low-emissions steel and then export that steel.”

On the drive back toward the city, Noel – forever dedicated to fostering a can-do mindset here in SA – is buoyed by the stories he’s heard of innovative, environmentally sustainable potential in South Australia’s resources sector.

“The other very important thing, though, is to make sure that some of the money generated stays in South Australia – that all this innovation benefits the people here,” he says.

He and Josh begin to discuss examples where this already happens – talking about how enterprise – from a small pub servicing a mining town to an internationally owned steelworks that chooses to hire local – can bring much needed money to the state.

Josh is keen to point out that this effect can be multiplied when individuals opt to shop local, keeping the money in their community for longer.

Listening to them talk, even when the examples are complex, the economy begins to seem simple again.

South Australia has the raw materials – the sun, wind, stone, minerals, and fertile soils. It’s got people with good ideas who can add value to those raw materials. And it has capacity for innovation to ensure that use is sustainable both for the environment and for communities.

With the University of Adelaide as our guide, we’re seeing through the fog of economic complexity and the clouds of the COVID-19 downturn, to the rays of light shining for SA.

Read/watch part one of our three-part series, ‘What Even is the Economy?’ here.

The Linwood Quarry is a suburban mine operating since 1885