Colonisation’s worst nightmare

Words: Angela Skujins

Pictures: Jack Fenby

Patches, signet rings and tattoos brand the members of the political, Aboriginal-only biker group Black Death IPC. A drive for revolutionary change propels them forward.

Seven motorcycles roar down Princes Highway in late December, speeding towards Raukkan – the birthplace of inventor David Unaipon, whose face, church and community totem (the swan) sit on the Australian $50 note.

Above the twisted light refracting off the hot asphalt, the leather-clad riders slowly raise their fists into the air. Like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, a trail of portentous dust flies behind them.

Their group’s Ru Puli (meaning ‘leader’ in Ngarrindjeri) is at the head of the pack – Mulla Sumner, a Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri elder who’s tired of First Nations’ people suffering at the hands of police brutality and colonisation. He leads Black Death IPC (Indigenous Political Club) with a tightly balled fist thrust skyward.

“We’re pissed off with everything and in every way that we’ve been treated, not being listened to,” Mulla tells us.

“We’ve seen a lot, we’ve heard a lot, and what we’re saying now is enough is enough and we don’t give a fuck. You want to lock us up? Fucking lock us up. You want to eat us? We’re going to fucking eat you.

“You want to point a gun at us? We’re going to point a fucking gun at you.”

CityMag has seen flashes of the mysterious bikers at Aboriginal Australian repatriation ceremonies and protests. Outwardly tough, they guide the crowd forward from the saddle of their motorcycles, leading with the thunder clap of their engines.

After meeting them at one such event, they invited us to learn more about the group by visiting Raukkan, Mulla’s birthplace.

Mulla dismounts from his custom-painted black motorbike at the coastal town, located 80km south of Adelaide. The land he comes from has a chequered past. “We was already here; the Ngarrindjeri people were already here,” Mulla says.

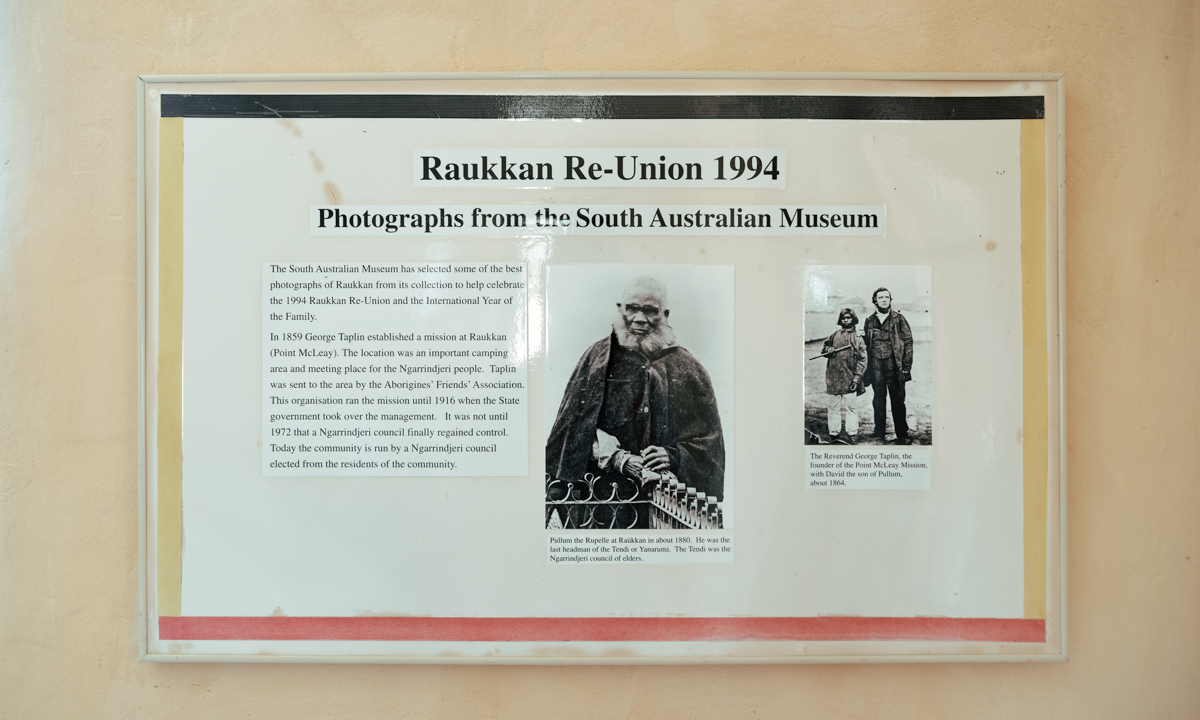

Until 1982, this community was known as Point McLeay Mission, which was set up to house Indigenous people forcibly removed from their Lower Lakes lands. The 1997 Bringing them Home Report found the mission built a school with the aim of distancing Indigenous children from their family and community influences.

Mulla is a totally tattooed figure, wearing a Che Guevara hat backwards and a leather vest plastered with “fight or die” and “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Tribes United” patches.

Despite the hardened exterior, he slowly reveals himself to be a sweet older man, who seems coarsened only by the sum of his stories. Mulla points over the small Raukkan hill to a hospital where he was born in 1949. “I’m the gang of ‘49,” he jokes, referencing the fake Aboriginal gang The Advertiser invented out of a spate of unrelated crimes in the late ‘00s. “That’s what the police reckon, too.”

After leaving two outlaw motorcycle clubs and being one of the first Aboriginal Australian One Percenters, Mulla started his own group in 2000. He devoured books about US Black power activists from the Black Panther Party and Native American protesters from the American Indian Movement. He wanted to create a similar organisation at home. He would forge this movement from materials he knew – steel, petrol and the camaraderie that exists between motorcycle riders.

Black Death IPC was founded to be a staunch, physical presence at protests, unafraid of staring structural and systemic racism in the face while fanning the passion of their contemporaries. Passionate about First Nations land rights and repatriation, the group also has a particular focus on spotlighting Aboriginal deaths in custody. They aim for some or all of the 22 members to be present at coronial hearings or inquests.

Their presence has not always been welcome. In May last year, Black Death IPC attended the memorial of 29-year-old Indigenous man Wayne Fella Morrison, who died in 2016 after being pulled unresponsive from a Yatala Labour Prison van.

After the memorial, Mulla received surprising phone calls. “I was getting death threats,” he explains. “They rang me up at home: ‘You and your crew are dead.’ ‘Oh, yeah. Right.’ ‘You’re just dead.’ ‘Right, who’s this?’ ‘You’re just dead.’

“I’m not worried about them. I got enough fellas around me to know anyway. Anything happens to me, they’ll know. If I get knocked off my bike, something like that, by a car. They’ll know what happened.”

The issue of Indigenous deaths in custody is personal for Mulla, who claims to have once shared a cell with an Aboriginal man who died after failing to receive medical care from a prison guard (or ‘screw’).

“He was calling to the screws, ‘Open the door. I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe.’ The screw came around, who was on duty that night, told him to ‘Shut up or we’ll charge you with causing a disturbance.’ Next day the bloke was dead.”

CityMag tried to verify the death with the SA Department for Correctional Services. A spokesperson said it was an offence to disclose information relating to a prisoner, probationer or parolee without their consent.

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was established in 1987 as a response to growing anxiety surrounding high levels of Indigenous Australians dying behind bars.

According to a 2019 Federal Government report looking back at the 25 years since the commission’s inception, 2044 Aboriginal Australians had died in custody between 1991 and 2016. Of those deaths, 101 were in SA. Mulla says the death he witnessed was never recorded.

Another reason we’ve met at Raukkan is because Mulla believes the past is connected to the future. Fixing some of the contemporary problems Aboriginal people face lies in understanding what has happened in the bloody history of days gone by. Truth-telling.

“We got to look at the past before we can go on. I don’t care what anybody says,” Mulla says.

Standing outside the stone Raukkan church, built in 1869, Mulla waves to someone called Marocc. Soundtracked by a ringtone beeping The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’s theme song, Mulla informs us the group’s membership isn’t solely bound to Aboriginal Australians. The group is advocating for First Nations people across the world, so “anybody who’s been downtrodden or oppressed” can join. Three other club rules exist.

“You can drink alcohol, but don’t make a jerk of yourself,” Mulla says. “I don’t give a rat’s [arse] about anyone smoking dope, as long as they don’t smoke it in my house. If you’re on hard drugs, we’ll take you around the back of the building and bash you.”

This tough approach comes from a place of pain. Four of Mulla’s siblings have died from drug overdoses, with three passing away within eight months of each other. Mulla also claims one of his sisters, Alva Sumner, had her baby taken away by SA Department for Child Protection (DCP) in the 1960s. She overdosed on heroin and died a week before they were due to meet.

When asked to verify this story, the department did not respond to specific questions. However, DCP Deputy Chief Executive Fiona Ward responded in a statement saying the department acknowledges the “significant impact” of past government policies that removed Aboriginal children from their families and communities, and that those effects are still strongly felt today.

But Mulla believes this is still happening. “The kids are being taken away again. It’s happening through the DCP,” he says. The most recent Family Matters Report (2021) revealed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children continue to be removed from family and kin at disproportionate rates compared to their non-Aboriginal counterparts. They are 10 times more likely to be in out-of-home or permanent care than other children in Australia.

We walk through the recently built Raukkan gallery and museum, which displays eerie black and white photographs of town inhabitants from the 1930s. They look like mugshots.

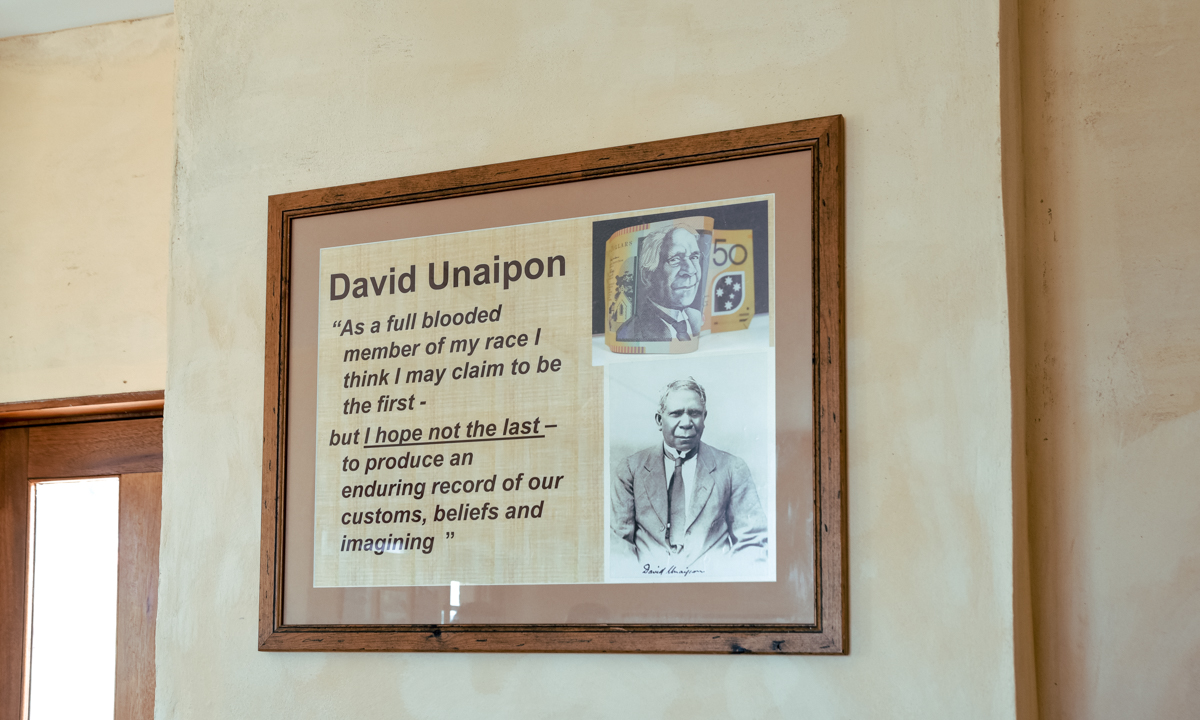

We see a portrait of David Unaipon, the Ngarrindjeri man responsible for creating at least 19 patented inventions in the early 20th century.

The design of one of his most famous innovations, a modified handpiece used for sheep-shearing, is printed on that Australian $50 note. “A man before his time,” Mulla remarks.

One of the other longest-serving Black Death IPC members, Les Graham – who also plays lead guitar for reggae rock group No Fixed Address – speaks to us about his upbringing in Murray Bridge. Historically, those who spoke their first language in his community were whipped, he says. He gazes with a solemn eye over the old photographs.

We enter the church and leave the other members outside. Here, Mulla shows us a plaque in tribute to Ngarrindjeri veterans who served in World War One. He recalls the recent reburial of Australian Private Miller Mack, who died in France in 1919 after contracting tuberculosis. The soldier was originally buried in a pauper’s grave outside of the designated military section at West Terrace Cemetery. After finding a suitable resting place, the Aboriginal veteran was reburied by his family in Raukkan five years ago. Mulla and Black Death IPC led the hearse.

Black Death IPC has an entirely Australian reason for being, but still Mulla is inspired by emancipation struggles from around the world. We begin to speak about South African apartheid and how pivotal Nelson Mandela was to that story. Mulla is waiting for an Aboriginal Australian leader to free his people here.

After touring Raukkan, we follow the others to their Airbnb, located five minutes outside town. The property is surrounded by miles and miles of dry yellow wheat and dirt.

From across the living room dining table, Greg Campbell says he’s another Black Death IPC member, but like his patched-up brothers, doesn’t know which mob he belongs to. He knows he’s Aboriginal, but because his forebears were part of the Stolen Generation, the details are lost. “I’m a member of the group to change things,” Greg says with a firm stare.

“Indigenous people, we get treated like shit all the time. They’re still doing it now. They’re saying they’ve changed things, but they never do. I’ve got no family. I’ve only got my brother, so this is my family.”

As Mulla removes his leathers to show us his chest tattoo, we notice something hanging off a piece of leather around his neck. His gold signet ring shines brilliantly as he points to the object. It’s a shell, he explains, from the Coorong.

“That’s what’s left in the shell after so many years of tumbling in the sea. That’s just the inside part. That’s the hardest part,” he says.

After decades fighting against the currents of European settlement, there is a toughness that remains within this Aboriginal elder, too. It is his dedication to standing firm for his people.