To find out why the interior of Leigh Street's Shōbōsho will be different to any seen before in the city, we met a man for whom playing with fire is an everyday occurrence.

How to make a restaurant: The art of shou sugi ban

Artistry is often found in the details.

It’s only upon closer inspection that you might see the effort and attention to detail that has been put in to crafting anything from a song, a television show, or a restaurant.

CityMag is chronicling the process of opening a new restaurant in real time with Shobosho – a new restaurant from Simon Kardachi and team that is set to open on Leigh Street soon.

Other stories in the series include –

Shobosho comes to Leigh Street

For the maiden diners of Shōbōsho on Leigh Street, passing through the glass frontage and up the wooden stairs for the very first time, it’s likely little else will be noticed apart from the bursts of flame flashing from the open kitchen and the incredible smell of meat charring over fire.

The kitchen was designed to be a spectacle, and punters, CityMag included, will surely oblige.

But perhaps on the second or third visit (Adam Liston’s yakitori will call you back), you’ll notice the black timber that runs along the stairs and behind the kitchen and you’ll wonder how that came to be.

The answer is shou sugi ban and a man named Mack Wilson.

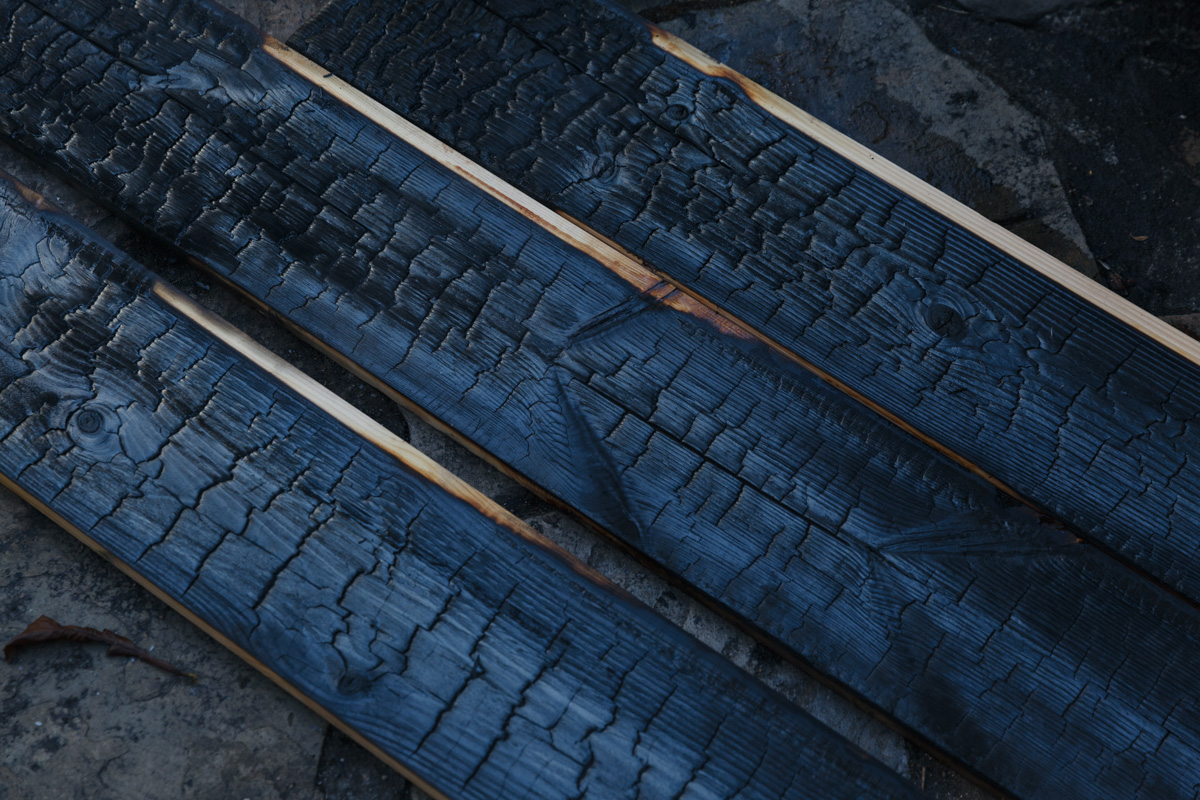

“This is not completely finished, they’ve been through one, two, three processes. They’ve still go another two to go to get them ready, but this is an example of the finish that we’re going for,” Mack says, showing us a small stack of the smooth blackened timber he’s treated.

Shou sugi ban

Mack has welcomed us to his home to see the shou sugi ban process firsthand, and it starts with a demonstration of the traditional Japanese method.

Mack fastens three planks of timber into a triangular tube, stands it upright on a makeshift brick platform, and lights a fire beneath it.

As the flames climb through the tube and start to flare out of the top, we ask Mack how familiar he is with the traditional method. He smiles and replies “No comment.”

“So that’s what you want, once you’ve got that flame out the top, that way you know that it’s cranking all the way through… It’s essentially a little mini rocket stove,” Mack says.

“So shou sugi ban translates to, shou means fire, sugi means Japanese cypress, it’s a timber type, and ban means half: so half-burnt cypress.

Baltic in the raw

“Technically this isn’t shou sugi ban, because it’s not sugi, it’s Baltic, so it’s shou Baltic ban, if that makes sense.

“As I understand, this process was developed in about the 17th century [and] it was done as a cheap alternative to driftwood, right? So driftwood… is a highly prized timber, because it’s full of salt and it’s been sitting in water for, who knows, hundreds of years, perhaps, and that’s used as a cladding.

“But basically they mined the beaches of this material, so they were like ‘How do we emulate this?’

“Now, this is going to be used for an internal application in this restaurant, which is sort of not what it’s intended for, because this is a seasoning process for external timbers to stop water, rot, that kind of thing.”

The decision is made to kill the flame on Mack’s demonstration, and he quickly drops the timber to the ground, douses it briefly, and unstraps it, laying the charred planks out for inspection.

“So this, when you do a traditional Japanese thing, is perfect. You do the two sides to that, you flip it, do the other side, and then that’s it,” Mack says.

Interesting though the traditional method is, it presents a couple of issues when creating a finish meant for an indoor application.

Firstly, the timber needs to be treated in such a way that there is no black soot left on the wood, so as not to transfer onto diners’ clothes; and secondly, to do every single piece of timber this way would take a terribly long time.

The commercial-grade fix is a charring implement that Mack calls the Death Stick, and though we lose light before we can get a shot of it with the intended blue flame, we’re still impressed with it’s priming phase.

Mack spent several years in Japan, during which he rode a bicycle across the country, working where he could and staying in temples.

In Japan, when a temple boards you, “you’re expected to give back,” Mack says.

“The temples in Japan that I stayed in are ranging from modern to 600- 700-years-old. They’re all made out of timber and no nails or screws, and so as repayment for letting me stay, I used to clean the temple, help them fix the temple, rake the garden – all the typical things.

“You’ve gotta get up at four o’clock in the morning and participate in the prayers and rituals and things like that… and in doing so, I really compounded my appreciation for Japanese carpentry, their techniques.”

On home soil, Mack’s business, Taringi, mostly sees him doing heritage restorations, while he’s often drawn back to Japan for shop fitting projects.

The drawcard for this particular job is bringing something authentic to a wide audience.

“It’s about substance rather than superficiality. You can get all the looks you want. People go through glossy mags and go ‘I want this, I want this, I want this,’ you know, [and] any spec homebuilder can go ‘Yeah, no worries mate, I can do that,’ and they do, but they really only give the superficial aesthetic to it, they don’t give that substance that gives it its authenticity, and I think it’s that authenticity that really is lacking in mainstream, but at the same time there’s a real revival of it,” Mack says.

“I think it’s definitely an opportunity for people to appreciate it, and I commend Studio Gram for putting something like this where it isn’t intended to be, so that’s why I’m excited to do it.”