Artist James Tylor gives context to SA Food Month in light of the first and continuous food culture of this state with this short encyclopedia of indigenous edible foods and agriculture in the Tarntanya Adelaide region.

The South Australian menu has always been seasonal

There’s nothing more iconic on a hot summer’s day in Adelaide than spending a sunny afternoon at Glenelg beach, swimming in the cold seawater and cooling down in the ocean breeze. And a beach trip is never complete without eating fish and chips, our favourite summertime food. These nostalgic days at the beach with family and friends become timeless in our memories.

Summertime at the coast has always been an important time for people in Adelaide.

At Holdfast Bay in Glenelg the British first arrived on the beach on a hot Summer’s day in 1836. The British were met by Kaurna people who were camping in the sand dunes.

Kaurna people have lived in the Tarntanya Adelaide region for over 49,000 years and have been camping on the coast at Pathawilya Glenelg for at least 10,000 years every summer since the water rose around the coast of Australia. This created the Wangka Yarlu Spencer Gulf at the end of the last ice age, which famously separated Karta Pintingga Kangaroo Island from the mainland of Australia.

Just like today, as well as 1836, the beach is much cooler on hot summer days than the Adelaide plains. For millennia Kaurna people embraced the seasonal changes of Adelaide and moved to the best place for food and shelter, away from the northern winds off the hot Australian interior in summer and the cold wet winds off the Southern Ocean in winter.

To understand and accurately celebrate a month of South Australian food, it makes sense to trace our food culture to its origins and the vibrant, resilient and complex agriculture of the first South Australians.

Ngangki pigface (disphyma crassifolium) bottom left & Karrkala pigface (carpobrotus rossii) top right

Muityu – fruit of the Karrkala plant

Warltati

Hot Dry Summer

Five Seasons

Pirira – bower spinach & warrigal greens (tetragonia sp)

Historically Kaurna people lived by a seasonal calendar comprised of five unique seasons, but today, because of the impact of climate change from global warming and the impact of European colonisation on Kaurna people, culture and environment, we only use four. That hot summer’s day in Pathawilya Glenelg, back in 1836 when the British colonised the South Australian mainland, marked a climatic change for Kaurna people. The introduction of the English language, western culture, exotic plants and the European calendar dramatically changed the Kaurna landscape of Tarntanya Adelaide from how it was once known. Warltati is the real name for Tarntanya Adelaide’s ‘summer’ and it stretches from the start of January to the end of March in the hottest and driest months. The warmer seas make it the best time to catch fish off the coast of the Wangka Yarlu Spencer Gulf.

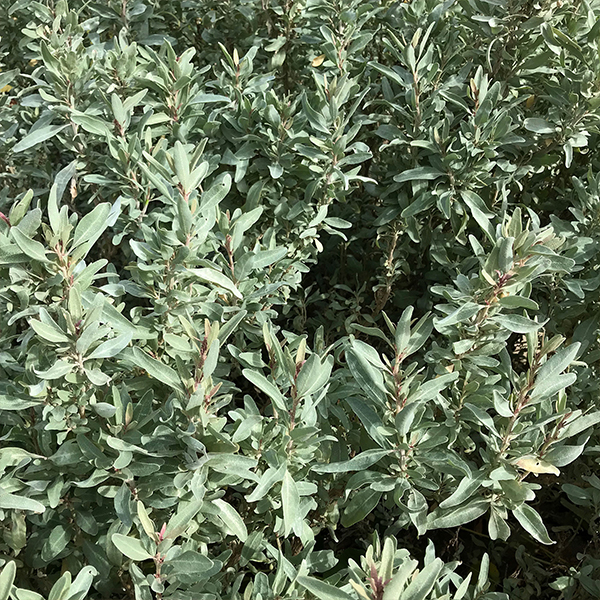

Niplina – saltbush (atriplex sp)

Wadni – nitre bush (nitraria billardierei) shaped like an olive but taste like sultanas

Coastal foraging

The dunes are the best place to camp in Warltati because the sand hills provide a natural wind break from the sea breeze. The dunes produce edible plants that are in season from November to February. Berries like mantarri (kunzea pomifera), wadni (nitraria billardierei) and muityu the fruit of the karrkala plant (carpobrotus rossii) are in abundance. Mantarri taste like sweet apples with a mild eucalyptus and strawberry flavour; multyu, the fruit of the karrkala plant, is similar to a sweet and salty flavoured feijoa. Wadni are shaped like an olive with a giant pip but taste like sultanas. Coastal vegetable such as pirira (tetragonia sp), ngangki (disphyma crassifolium) and karrkala are in season too. Ngangki and karrkala, commonly called pigface, taste like salty cucumbers. The coastal pirira bower spinach and niplina (atriplex sp) saltbush are nice leaf vegetables to eat too. You can still find all of these plants growing in the beach dunes along the Kaurna coastline of Tarntanya Adelaide and a great field guide to find these edible plants is Tim Low’s Wild Food Plants of Australia. You can also buy these Indigenous ingredients from Aboriginal owned Something Wild in the Adelaide Central Markets, who provide fresh Indigenous greens, berries, dry herbs and Indigenous meats in turn making it easy for people to access these local ingredients again that once grew under our feet in Tarntanya Adelaide.

Parnati

Adelaide’s Autumn Season

Fire farming

The appearance of the Parna star indicates the end of Warltati and the beginning of Kaurna’s Autumn season of Parnati in April and ending in June. Parnati is a transitional season with the temperature cooling down and the winter rains starting. The first month of Parnati is the fire-farming season. Tarnta tutha (Themeda triandra), better known by its common English name Kangaroo Grass, was a traditional cereal crop for Kaurna people. The tarnta tutha is harvested in the month of December, when the seed are still attached to the head of the grass. By April the remaining seeds have fallen to the ground. The first rains of Parnati activated the seeds on the ground to self-burrow into the soil, protecting them from the extreme heat of the fires. The tarnta tutha grass stems are still dry and catch fire in the controlled burnings. The smoke and ash from the fires fertilise the seeds now buried in the ground and without smoke the will lay dormant in the winter rains until there is a fire to begin their germination.

Tarnta Tutha – Kangaroo Grass (Themeda triandra)

Kangaroo grass bread

This system of fire farming is best explained by Bill Gammage in his book Greatest Estate on Earth. He highlights how Indigenous people used fire to farm the Australian landscape. Tarnta tutha was an important grain for Indigenous people of Southern Australia including Kaurna in Tarntanya Adelaide. Tarnta tutha was recorded by several colonists, but the best story is by Edward Stephens, who said “The site of the present Norwood was then a magnificent gum forest, with an undergrowth of kangaroo grass, too high in places for a man to see over; in fact persons had lost their way in going from Adelaide to Kensington in those days.” He went on to say how Kaurna made bread from the tarnta tutha “Small loaves of bread or damper were obtained, Johnnycake the latter was called. These were baked not in the ashes as the damper… They were about half an inch thick and six or eight inches in diameter, and were baked by being stood upright before the fire, supported by little sticks.”

Wardli houses

In April, during the second month of Parnati, Kaurna people would migrate from the coastal dunes to the forest on the Adelaide plains to build wardli houses. The migration was called waadla-warnka-ti, which translates to waadla ‘fallen log’ + warnka ‘in front‘. Waadlawarnkati is no longer in use following the arrival of the British because of European suburban life in the Adelaide City, but it is important to highlight the important historical Kaurna migration. Every year Kaurna would return to the same location to construct wardli houses out of fallen tree branches. The wardli were heavily thatched with grass and the entrance would face northeast from the cold southwesterly wind in the winter season of Kudlila. There was a small fire at the opening of the wardli to provide warmth and heat for cooking food.

Kudlila

The cold winter rainy season

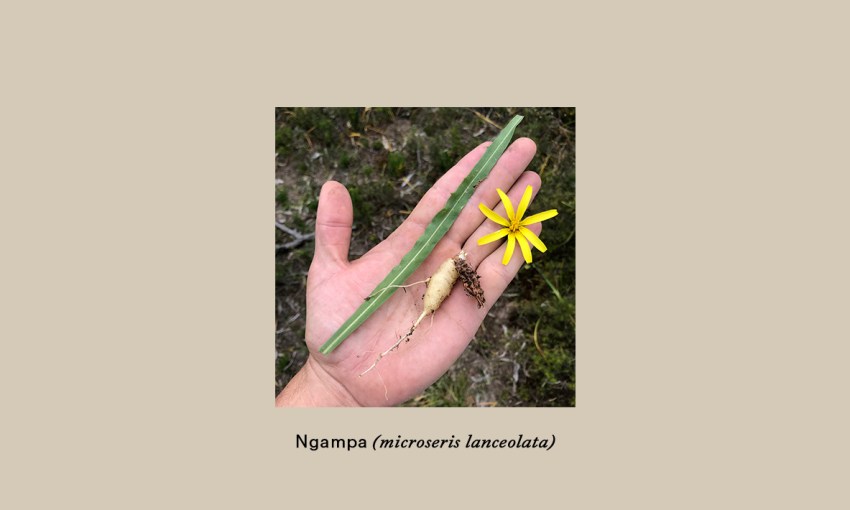

Ngampa – Yam Daisy (microseris lanceolata) yam daisy written about in Dark Emu

Ngampa Yam Daisy

The Kaurna winter season is called Kudlila after kudli, which means to wash and refers to the heavy rains that begin in July and end in September. The heavy rains stimulate new sweet green growth of tarnta tutha that attracts animals to the plains, providing food for the wartu wombat, nantu grey and tarnta red kangaroos. Just like the kangaroo grass, the yam seeds and tubers start growing again. This includes ngampa (microseris lanceolata), better known as the Yam Daisy, which has been popularised in Bruce Pascoe’s revolutionary book Dark Emu that explains the history of Australian Indigenous farming methods before European colonisation. He describes how yam daisies and kangaroo grass were cultivated by Aboriginal people as staple crops in Southern Australia.

Warnpa (typha domingensis) – river reeds home to water birds

Water birds

The much-needed rains in Kudlila provide water to refill the rivers, creeks, waterholes and swamps and attract waterbirds like ducks, geese and swans. The eggs of these birds were a food source for Kaurna people. These birds built their nests in the river reeds of the warnpa (typha domingensis) and witu (phragmites australis). The roots of warnpa and witu are edible and were traditionally cooked in large earth ovens.

Wirltu

The Southern Cross makes the Spring Season

Kurti – quandong (santalum acuminatum)

Spring berries

The position of Wirltu tidna the Southern Cross in the sky indicates the start of the Wirltuti Spring season that runs from October until the end of December. The Southern Cross is called Wirltu tidna because it resembles the foot of wirltu the wedge tailed eagle. The nesting birds like the wirltu that laid their eggs back in Kudlila season are now hatching and leaving the nest for the first time. The rains begin to ease and the weather to warm in Wirltuti. At the start of Wirltuti, Kaurna people traditionally would migrate back to the coast. Root vegetables like ngampa and walyu (arthropodium sp) begin to flower, which makes them easy to find in the long tarntu tutha. The winter rains made the tubers big and juicy and late Wirltuti is the best time to harvest the large yams because they are starting to go to seed. Late Wirltuti is also the best time to pick the sweet berries of kurti (santalum acuminatum), pakiyaka (acrotriche depressa) and nalalatu (astroloma humifusum). You can try these berries in delicious recipes in the new Adnyamathanha cookbook Warndu Mai by co-owned Indigenous company Warndu.

Walyu chocolate & vanilla lily (arthropodium sp)

Pakiyaka – indigenous currant (acrotriche depressa)

120 edible plants

The effect of European colonisation that began on that day back in December 1836 at Pathawilya Glenelg has massively changed the Kaurna landscape that we once knew. Indigenous plants and animals that once lived on the plains and were important food sources for Kaurna people are now rare or regionally extinct, like the mapu eastern quoll or pingku bilby that Pingku Wama Pinky Flat is named after.

The urban and industrial sprawl of metropolitan Adelaide has dramatically altered the landscape and the Tarntanya Adelaide climate. Global warming has lead to climate change from Western industry and globalisation has further changed our region’s weather patterns, making weather patterns harder to read and further impacting our flora and fauna.

One simple solution that people in Adelaide could use to combat climate change is to understand our climate better through the Kaurna calendar. The Australian Bureau of meteorology has made a Kaurna calendar that people can easily access on their website. A second way is to grow and eat local Indigenous food. Neville Bonney has published several books on how to grow, harvest and cook edible South Australian Indigenous plants. There are 300 species of plants in the Tarntanya Adelaide region that Kaurna people use and 120 species are edible. Today the average person in Tarntanya Adelaide doesn’t eat any Kaurna Indigenous plants.

Regardless of whether Tarntanya Adelaide is willing to engage with Kaurna foods or the Kaurna calendar our seasons are changing, but let’s try move them back in the right direction.

CityMag is celebrating the best food and drink businesses in Adelaide throughout July

CityMag is celebrating the best food and drink businesses in Adelaide throughout July