Adelaide’s golden era of graff

Words: Angela Skujins

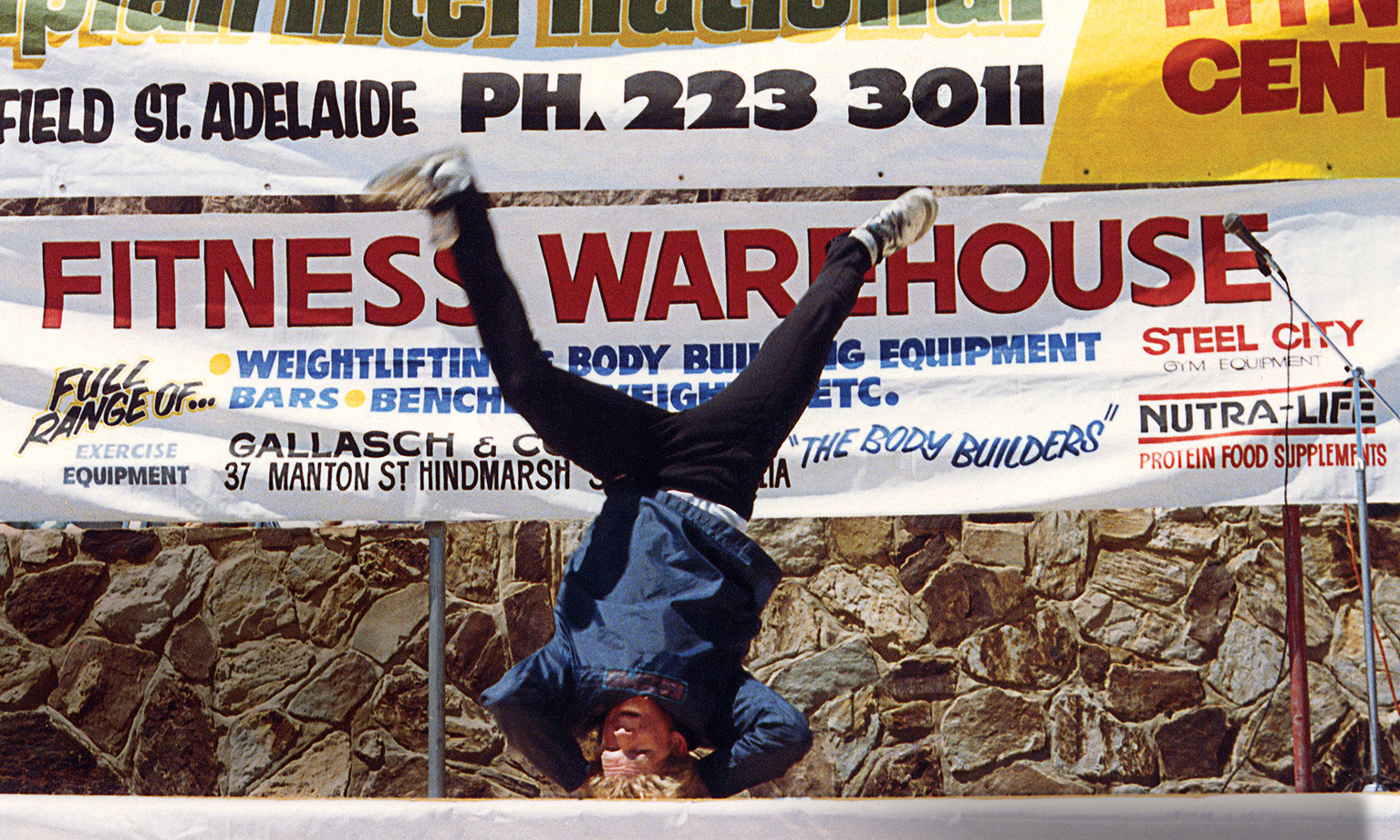

Pictures courtesy 'WILDFIRE: Australian Graffiti LIVE FROM ADELAIDE' and Puzle Press

Social historian and muralist David Houston has been a part of the city’s graffiti scene for 36 years. He recently authored a book titled ‘WILDFIRE’ that traces the movement’s golden era in Adelaide from 1983 to 1993, with arresting photographs and stories from its key players.

David brings the clandestine and colourful world of graffiti, inhabited by outcasts with friendships forged on walls, to the surface.

“You can do it in the dark of night, you don’t have to apply for permission, and all you need is a bit of get-up-and-go – and some paint – and the sky is the limit,” David Houston tells CityMag.

David first picked up a spray can when he was a 13-year-old Glenunga High kid in 1985. He hasn’t put it down since.

This first encounter with graffiti was roughly one year after Adelaide’s scene truly kicked off.

David says the movement began in the postcode 5000 with a rag-tag group of school friends who spent every waking minute poring over record covers and break-dance films, while scouring book stores for the highly sought-after New York publication Subway Art, for any scrap of information on the subculture.

Decades later, in 2021, David (right) published the 246-page book titled WILDFIRE: Australian Graffiti LIVE FROM ADELAIDE, which tracks the “golden era” of graffiti in Adelaide from its 1983 origins until 1993, when the lauded Red Hen trains were taken out of service and the scene solidified itself artistically.

“A lot of the guys that were doing this naive artwork in the ’80s honed their skills a lot more and hit their straps by the ’90s,” David says.

“So you really start seeing really sort of creative artwork, that even Joe Blow on the street would appreciate.”

David spent 12 years compiling notes on this era, reaching out to fellow “graffiti writers” in London, Denmark and even Darwin for their accounts and photographs. Rather than just posting the history online, like some of David’s contemporaries had, he decided to turn it into a book.

“I thought that time deserved more than that,” David says.

“I loved it more than that. I treasure it more than that. And I refuse to cheapen what we did and how we did it by just wasting the images online.”

The result is an intimate account of the (mostly) underground world of graffiti, and the author’s role in it.

“There can be no certainty which was the first graffiti piece painted in Adelaide,” David writes in WILDFIRE. “However, what is substantiated by photographs and corroborated by Adelaide graffiti folklore is that tags began to appear on neighbourhood walls and trains in Adelaide by at least 1983.”

As the book says, the movement was kickstarted by a group of artists, with tags such as Wicky, Nitro, Sparky and Lee Fresh, in the early ’80s.

David – who runs with the penname Pho (not to be confused with the Vietnamese noodle soup) – says the first piece he ever laid eyes on was Wicky’s Fresh and Funky.

The now father-of-one says in the past he was an “angry kid” who had a “difficult childhood”, so throw art in the mix and “graffiti really suited me,” David says.

He believes it was the same for other artists, often enrolled in the school of “Hard Knocks”.

“With these groups, you grow up together and it’s not just always about graffiti as well,” David says.

“It’s the whole teenage angst and the stuff that goes on in relationships and… all these sorts of things everybody else experiences in every other subculture, or [what] they’re doing as teenagers.”

Back in the day, there were no retail stores like Clinic 116 or Da Klinic selling rows of spray paint or street markers to Adelaide artists. David says this would force maverick muralists to source any aerosol available.

“It’s trial and error. You’re trying all this different paint, [such as] sheet spray, hairspray, enamel. Some of it does work and serve a good purpose, but some have more longevity than others,” he says.

“If it was automotive paint, or it was enamel paint, you had about 12 colours. You grab one here, one there, mixing and matching, just trying to see what happens.”

But before you even got to a site to graffiti, either illegally or with permission from the landholder, you went to the Writers Bench. Originally this was a literal bench out the front of Rundle Mall’s Myer Centre that served as a gathering place for young artists and friends to share designs for upcoming works.

You also went there after a successful spray “to show one another physical photographs or tell them tales of what you did the night before the week before,” David says.

Today the bench has been replaced with online sharing platforms, such as Instagram, but camaraderie still exists.

“It’s just a whole lifestyle. It’s a 24 hour, seven-day-a-week sort of thing,” David says.

“Whether you’re sourcing the paint, you’re drawing the design and you’re planning what you’re going to do, whether it’s the whole artwork really. If that’s in the dark of night, or during the day with permission or whatever, there’s a lot more involved.”

So much of graffiti culture revolves around social relationships forged together on a wall.

This includes the egos that come with one artist being the top dog, who can do the final outline with a steady hand, because “they’re a little bit neater than everybody else,” David says.

But also because there’s a right and wrong way to go about laying down a piece, and the reality that your piece will eventually be covered over.

Whether the public likes it is another story, David says.

When we ask David about his thoughts on council-approved walls for graffiti, such as the Morphett Street bridge, he believes it’s good those spaces exist, but the artworks on those walls only exist for an instant before they’re covered with something new.

“When I was younger, there weren’t a lot of venues where you could just paint, or outlets where you could just paint,” he says.

“If you want to be involved with it all, you were forced to break the rules.”

As well as compiling analogue film photographs and accounts from those within the pioneering group, WILDFIRE also includes news stories.

One 1985 Sunday Mail story about Adelaide’s 20-year-old graffiti “king” Wicky (real name John Reynolds) includes quotes by “graffiti expert” Dr Alan Spry, who said, in an indirect quote, Adelaide is a “victim” of world trends. The article later explains the taxpayer cost of covering up the vandalism.

When David is asked his thoughts on the criminality of graffiti, he believes the public’s understanding of the art form has changed since 1985. But there will always be detractors. Even today.

“But the book goes beyond all that,” he says, “because it’s more about social history.”

“It happened in naivety. In the first 10 years, we didn’t know what we were doing. We were just absolutely flying blind, there’s no internet to surf.”

This Saturday, 28 August, Currie Street’s Arthur Art Bar is celebrating the release of WILDFIRE, seven weeks after publication.

The book launch is running from 1pm ’til 3pm, and will feature some of the founding graffiti artists and those who belonged to the “second wave” – such as David himself – for book signings (read: tags).

“It will be a celebration of our youth”, David says, and a party not exclusive to graffiti writers. It’s for lovers of all things artistic, or those who dipped their toes in any counter-cultures, such as hip-hop or breakdancing,” he says.

Like all good things, however, the golden era eventually went dark. David says this was solidified when the Red Hen trains were taken off the tracks around 1993, and a lot of writers lost their favourite walls.

“We really book-ended the timeline with the Red Hens being scrapped, and all the writers then moved on,” David says.

“Love it or hate it, graffiti is about painting trains.

“Back in the day, that’s really what it was all about, and this idea of painting the train so that your name travels around the city and your artwork gets more exposure than just staying stationary in one spot.”

Purchase ‘WILDFIRE: Australian Graffiti LIVE FROM ADELAIDE’ published by Puzle Press through this link. More information on the book launch can be found here.