Lost work, cold homes, and confusing governmental information – these were some of the challenges the lockdown brought to disadvantaged communities in Adelaide, with one organisational head calling it “a class-based pandemic".

The uneven impacts of the seven-day lockdown

SPECIAL REPORT: COVID-19 ADELAIDE

For some, like this reporter, working from home is a luxury.

Although my Goodwood rental is icy at times (I can often see my breath in the kitchen and bathroom), I’m thankful to still have a job and money coming in.

I’m able to pay bills and run a heater without worrying too much about my budget.

This is not a comfort afforded to all South Australians, though.

A portrait of the journalist in an Arctic Circle-approved puffer

When the state was plunged into a seven-day snap lockdown due to the Modbury cluster, some in the state shivered through bitter conditions, wrangled serious mental health issues, and wondered how they were going to keep the lights on.

Some people living through this uncertainty reached out to AnglicareSA.

“We did get an incredible spike in people worried about the future, for example, who didn’t know how long the lockdown was going to be and therefore whether there was going to be more electricity used for heating,” says AnglicareSA Executive General Manager, Community Services, Nancy Penna.

“There were some who worked part-time in the casualised workforce and were thinking, ‘I’m not going to be able to pay my bills in future, what do I do?’”

On Wednesday this week, Adelaide’s dusted off their masks in order to safely rejoin public life, but CityMag wondered what lessons might be learnt from looking back at the lockdown.

We spoke to experts working in social services about how their communities fared, and how issues could be ironed out in the future.

LOWER SOCIO-ECONOMIC COMMUNITIES

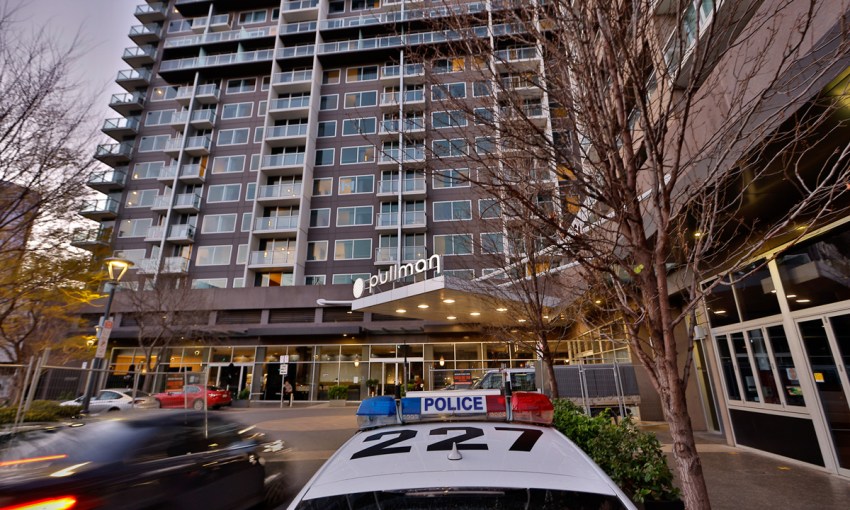

This picture: AAP/James Ross

As in previous lockdowns, AnglicareSA offered a range of services throughout the most recent seven-day experience, including emergency housing provisions, financial and emotional counselling and food drop-offs.

“You’ve got a lot of people who are employed in more casualised work and so a sudden drop of income, they usually don’t have the reserves that others do, and that in itself is incredibly difficult,” Nancy says.

“Secondly, when you’ve got children working from home, not everybody has the range of devices that can keep everybody occupied, and also [the] space.”

Anglicare holds a large purview over the metropolitan Adelaide, but Nancy says they concentrate a large amount of their energy in the northern suburbs, particularly in Elizabeth.

This area often reports high unemployment figures, which Nancy says means the people living there will experience lockdown differently to those bunkered down in more affluent areas.

“For people in the northern suburbs, in particular, because they don’t have the resources backing them so [they] can sail through a difficult period, or unexpected expenses or unexpected situations, that just adds further to the stress,” she says.

“There had been some reportage in the media, and if you go online there’s tier one and tier two [sites], and we had a few people that had rung saying, ‘We’ve got no food, we can’t go shopping because we were in a hotspot.’

“We had a few cases like this in the north, where we said, ‘We’ll go do the shopping for you, we’ll drop food off at your house.’”

Nancy says AnglicareSA and SA Health have streamlined their service provision significantly since the original lockdowns last year, but the information needs to be clear.

And while there is an emphasis on tactile help, such as food deliveries, mental health help also can’t be neglected.

“We have other services, one is in the suicide prevention area, and living beyond suicide, and what we did see is that the contacts with the services did increase over the lockdown period,” Nancy says.

“Maybe there needs to be more communication around if you’re feeling concerned, if you’re feeling anxious, these are the contacts and this is what you can do.”

MIGRANT COMMUNITIES

This picture: Masjid Pogung Dalangan

Deb Stringer is the CEO of the Australian Refugee Association, which also operates out of Adelaide’s northern suburbs.

The not-for-profit’s operation helps refugees, asylum seekers or migrants acclimatise to their new lives Down Under.

Deb tells CityMag that during the seven-day lockdown, clients reached out to staff and caseworkers asking when they could be vaccinated and for help translating government information.

“There are masses and masses of information that mostly can’t be read, and often when it’s even in the language of a community, many people can’t read in that language,” Deb says.

“If you’re a person whose first language isn’t English [and] you don’t actually read and write in your own language, negotiating what are essentially mainstream communication forms is really challenging.

“From what I’ve heard from my staff – people are very good and they understand the need for these short sharp lockdowns, but probably the most pressing issue for people is when they can get their vaccine and where they can get it from.”

Like Nancy, Deb believes what’s been missing from these lockdowns is clearer government messaging from SA Health.

Information also needs to be communicated outside of the mainstream media machine.

She believes “word of mouth” is one way to reach non-English-speaking communities.

“If you’ve got a mosque on a weekend where you get 200 people or a church or whatever, or you get a community and bring 200 or 100 people together in the right space… I think having those kinds of more grassroots conversations is what’s been missing,” Deb says.

“What the pandemic has shown us is just how it has affected migrant and former refugee communities more so than many communities because [they usually consist of] larger families, less internet access, less digital technology, more casualised work, working in the caring sector such as aged care, disability care – there’s more risk.

“It’s been quite a class-based pandemic in some ways, because it’s easy for those of us who’ve got an office at home to work at home and do a lot of the things that we have been meant to be doing.

“But I do think it’s shown… where the gaps in the inequalities are, to some extent.”

ROUGH SLEEPERS

This picture: Tony Lewis

The Hutt St Centre in postcode 5000’s southeastern quadrant helped 80 people a day during the lockdown, says CEO Chris Burns.

There was also a “noticeable increase in new people” seeking help from the centre, he says, which offered primary wellbeing services such as meals, showers, laundry and medical support.

“Rough sleepers and people with no permanent place to call home generally have poorer health than the rest of the population,” he says.

“It’s important our doors remained open to provide ongoing health and wellbeing support.”

Many of those experiencing homelessness did not have the financial means or “confidence” to go food shopping during the lockdown, Chris says, so meal packs were delivered to people housed in the State Government’s temporary emergency hotel accommodation scheme.

Despite the Hutt St Centre receiving “no State Government funding [or] support” for these offerings, Chris is proud of the case managers, kitchen team, and support staff helping vulnerable people in the community.

Although the Minister for Human Services Michelle Lensink circulated a press release saying “help for vulnerable to continue post lockdown”, which “could” include public housing, community housing and boarding houses, Chris is not entirely confident what will happen after restrictions lift.

“Our great concern is… when people experiencing homelessness will have to leave the emergency hotel accommodation, which was available for the lockdown period only,” he says.

“These people will have no choice other than to return to the dangers and risks of rough sleeping on the streets, which will be especially challenging with the inclement weather forecast.”

If this story raised issues for you, call LifeLine on 13 11 14.

Call the SA COVID-19 Mental Health Support Line on 1800 632 753 if the COVID-19 news cycle is affecting your mental health and wellbeing.