The cost of going green

Words and pictures: Angela Skujins

Additional pictures: David Washington (2010)

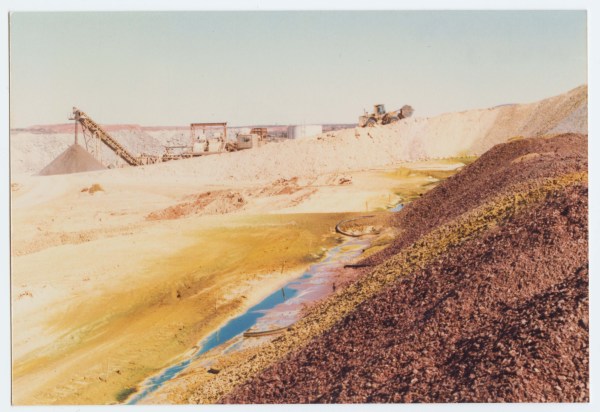

For almost 150 years, Mount Gunson’s sun-bleached hills have been mined for copper – a metal integral to the world’s electrified future.

Located out of sight more than 400 kilometres from the CBD, many believe generations of extraction have left the surrounding landscape in dire need of rehabilitation.

—

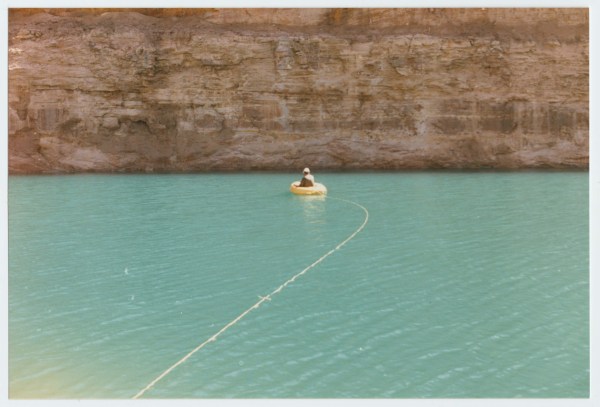

After a six-hour drive north from Adelaide, 130 kilometres short of Roxby Downs, CityMag arrives at a peculiar spot. A saltwater lake glows green, gnarled colossal cliffs rise nearby, and veins of emerald pop through the cracked dirt.

In the middle of Kokatha Country, which swirls with flies, saltbush and scrub, something is wrong – and has been wrong for decades. This 14-hectare patch of wild landscape is Mount Gunson.

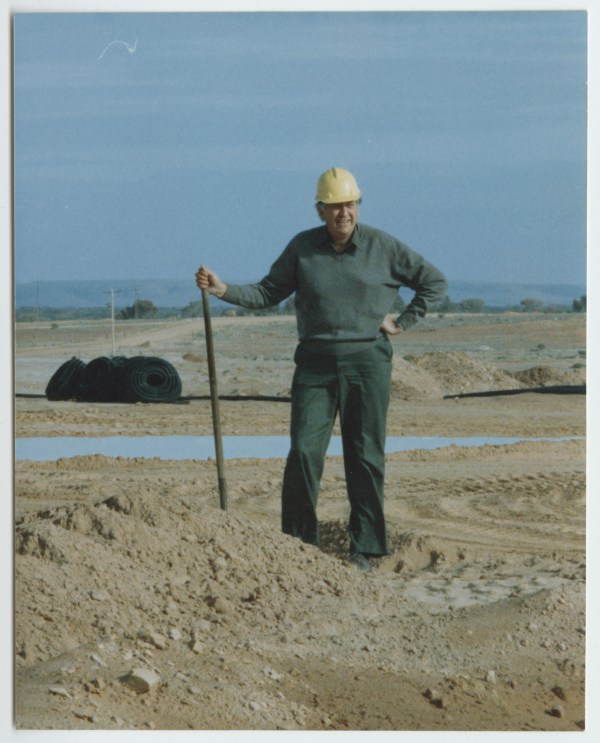

This picture: A Mount Gunson miner photographed by Graham Armstrong (1988) courtesy of the State Library of South Australia

For more than a century, South Australia has been known as the Copper Kingdom. In 1842, the metal – an element of electronic devices to come, like radios, televisions and mobile phones – was first discovered near the Mount Lofty Ranges.

This was only six years after South Australia was officially declared a colony, with copper booms developing blooming country towns. It drew growth away from metropolitan Adelaide, into a corner of the country where the endangered Pernatty knob-tail gecko roams.

Over the almost two centuries since, the reddish-brown resource has been uncovered and pumped out of monster-sized mines, such as Burra, Kanmantoo and Olympic Dam, the latter of which is now the fourth-largest copper deposit in the world.

In contemporary South Australia, copper is still the state’s leading resources export, producing $3.1 billion in the 2021-22 financial year. The Department for Energy and Mining states online these numbers make South Australia a national leader in copper production.

Copper is also vital to the state’s decarbonised future. It’s an easily recycled electrical conduit used in solar panels, windmills and electric vehicles. In November 2021, the previous South Australian government penned a Copper Strategy, in which it said it wanted to achieve one million tonnes of “sustainable” copper production with a focus on “green” copper. This means metal moved through environmentally friendly supply chains and sourced from zero-emission mines.

Former State Minister for Energy and Mining Dan van Holst Pellekaan declared in the Copper Strategy, South Australia was on the precipice of “exciting times”, as the best minds were “creating technologies to realise the broader opportunity copper can deliver so the world can live better”.

The current Mining Minister, Tom Koutsantonis, continued this theme, saying this year the government was proud to be a national copper leader: “The metal at the core of the global energy transformation.” The outlook for the valuable resource is only expected to grow, Koutsantonis says, as nations transform their economies to embrace low-carbon futures.

It’s clear the metal that has had a firm footing in South Australia’s past will hold well into the future.

And while the ministers of the energy and mining portfolios have long lauded the material’s impact on the state, stakeholders outside of government have raised questions about what happens to these copper-producing mines – the wellsprings of South Australia’s success – once they’re sucked dry.

The current condition of Mount Gunson, that strange place in the state’s north, and its neighbouring ephemeral salt lake Pernatty Lagoon have been described to CityMag as “contaminated” through the process of copper mining.

Traditional Owners of the area, an interstate sustainability expert, and an environmental lawyer are the voices calling for the sprawling and epic landscape to be rehabilitated. They also argue Mount Gunson is a case study, representative of other national copper sites, far-flung and hidden in the outback, out of sight and mind.

There have been 1.5 million tonnes – the equivalent of 50,000 trucks – of contained metal extracted from Mount Gunson since 1875, with the first smelter erected at the main open cut in 1904.

Although we don’t know what the area looked like before it was mined for the precious metal, it is surely far from its current state.

Kokatha came first

Throughout Mount Gunson’s mining history, the Kokatha people have maintained their connection to the land. The relationship stretches back millennia.

Glen Wingfield is the heritage services manager at Kokatha Aboriginal Corporation and it’s his job to protect special sites through the language group’s 140,000sqkm land area, spanning ephemeral salt lakes to dusty outback scrubland in remote western South Australia.

Wingfield says it was against “cultural protocols” to have Mount Gunson’s parallel lagoon, Pernatty Lagoon, “contaminated” by mobilised copper – which is moving metal, a by-product of decades of mining activity. The salt inlet and hills surrounding the lagoon sit within Kokatha land.

This picture: Graham Armstrong (1988) courtesy of the State Library of South Australia

“It’s damaged our site,” Wingfield says of the mining activity. “It’s horribly disturbed at that top there, the northern end, the north-western side.”

Wingfield says the site was part of Kokatha’s continuing culture through “community and storylines”. A 2006 report found a Kokatha “assumed [significant] site” was mined out by previous operators, sometime before 1987. The document also states there was “some risk” of continued mining activity disturbing undiscovered Aboriginal artefacts.

A 1973—1980 lease signed by Mount Gunson Mines Pty Ltd states the miners would “take due care to preserve and protect any items of Aboriginal or European Heritage”.

The lease also states the company would pay the government $70 per annum for mining access to the area, as well as a further yearly sum of 2.5 per cent royalties on all minerals recovered. Mount Gunson Mines would also “rehabilitate all areas disturbed by mining or ancillary operations to the satisfaction of the Chief Inspector of Mines”, the lease states.

CityMag asked the Department for Energy and Mining whether the site was rehabilitated to the Chief Inspector of Mines’ satisfaction, but we did not get a response. Mount Gunson Mines signed another seven-year lease in 1989, stating they would “at all times keep and preserve the mines and premises in good order”.

Before miners travelled to Mount Gunson in search of ore, Wingfield says the lagoon was integral to Kokatha’s story. Now, the community does not want to visit the area. “It’s broken the tranquillity, the mines,” he says.

The Federal Court of Australia’s determination document states the Pernatty pastoral lease – an area next to Mount Gunson – is part of Kokatha’s “other interests and relationships”.

Kokatha’s connection to this area is further cemented by the document, which cites evidence of “resource use” – Kokatha people hunting various lizards around Pernatty Lagoon.

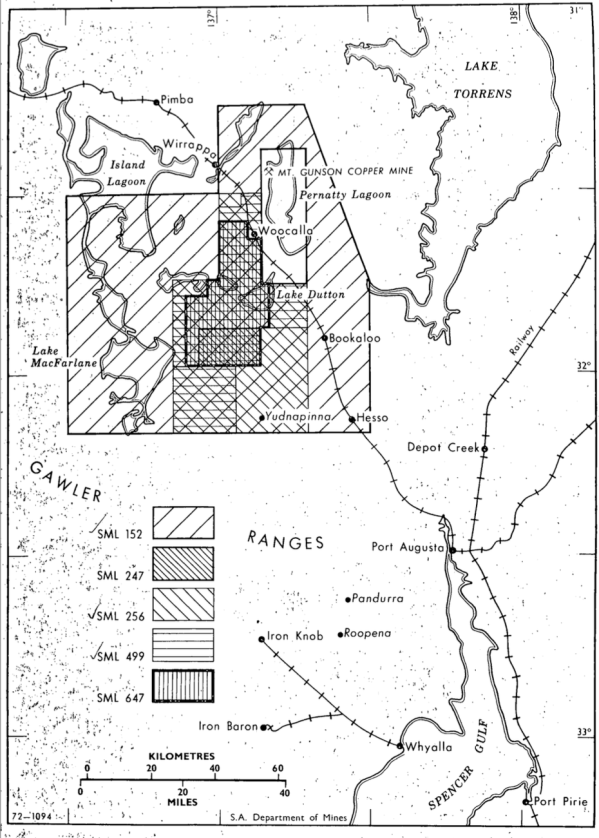

A 1972 map of the region

Wingfield says the local community had been worried for years about the site because of the impact it has on fauna, the environment and Kokatha culture. He says no animals venture near the lagoon.

“You can see the nice green aqua that’s running down and into the ponds and into the lake bed? The huge amounts of ore deposits, sand deposits, mineral deposits that have been left over; [it’s] leftover malachite,” he says.

“That’s the leftovers from all the chemicals or stuff that they just left over and put out into those ponds.”

As of 30 June 2022, there were 527 mining operations in South Australia, the Department for Energy and Mining spokesperson tells CityMag. Of these operations, 377 were ‘producing’ – meaning they have submitted a royalty return in the last three years, including a nil return, and 261 had an extractive mineral lease.

Sixty-five had mineral leases looking for metallic, industrial or uranium materials. The remaining 58 producing mines were private and producing “various commodities”. One-hundred-and-fifty mines were not producing at all.

The Department for Energy and Mining states online only three mines are being actively rehabilitated by the Mineral Resources Division. These were the Adelaide Hills Brukunga mine, Port Pirie treatment plant and the north-west Radium Hill mine.

Mount Gunson is not on this list.

A history of Mount Gunson

The early days

After copper was first discovered at Mount Gunson in 1875 and the subsequent smelter was established, various businesses have secured government contracts to scour the land for metals.

In 1974, former South Australian Director of Mines Bruce Webb published a report regarding the “base metal mineralization” (sic) of Pernatty Lagoon.

Webb, writing on behalf of the government in an introductory letter, said after a century of mining activity he believed information relating to what was happening at the site should be “more readily available to the public”. The report was written in 1972 by chief geologist R. K. Johns, and detailed Mount Gunson’s history as a mine to the mid-1970s, as well as a general surveyed analysis.

This picture: Graham Armstrong (1988) courtesy of the State Library of South Australia

From 1898 to 1937, operations lacking in purpose – or “desultory”, in Johns’ words – resulted in the production of 3250 tonnes of hand-dressed ore. Mining at Mount Gunson continued through the Second World War but stopped when the mine’s output declined to the point where a minimum grade of 2.5 per cent copper could no longer be obtained.

Operations picked up in 1965 when Mount Gunson Mines reopened the mine, producing mainly copper and limited quantities of silver and cobalt. In 1970, they started mining the “floor” of Pernatty Lagoon.

A fall in copper prices shuttered operations in 1971, putting the area into ‘care and maintenance’, meaning the mine was closed but had the potential to recommence operations at a later date. “Details of that company’s exploration are still held as confidential,” the report states.

In 1974, a sublease was obtained by CSR Ltd to mine another section of Mount Gunson. That same year, the “base metal mineralisation” report – released three years after the South Australian Mining Act came into effect – identified a “potential zone of weakness” for mineralised copper to migrate in the Pernatty and Mount Gunson areas.

Turn of the century

A Department for Energy and Mining spokesperson says local company Adelaide & Wallaroo Fertilizers (AWF) produced copper cement at Mount Gunson for their Burra processing plant from 1989 to 2006. According to the sale agreement at the time, “indemnity” was granted to the purchasers against “liabilities arising from all prior actions”, the department spokesperson tells CityMag. AWF obtained assurances from leaseholders and the department that it couldn’t be held responsible for “pre-existing site conditions”, said the spokesperson.

Mining Minister Tom Koutsantonis tells CityMag all modern mining operations required approvals to prevent legacy liability issues, and the recent establishment of the Mine Rehabilitation Fund would be a pathway for the government to “resource the rehabilitation and management” of historically disturbed sites.

He could not give an answer as to how much money was currently in the fund.

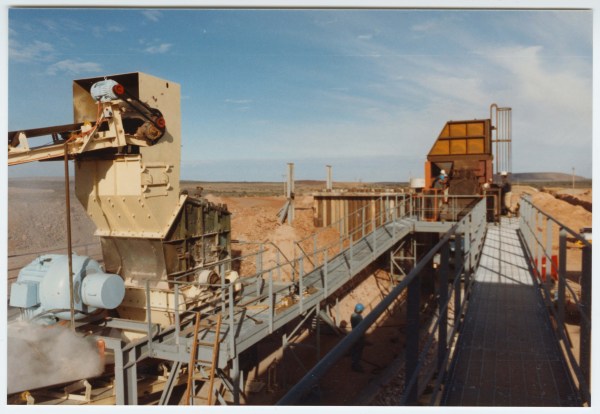

This picture: Graham Armstrong (1988) courtesy of the State Library of South Australia

In 2006, after most existing mining tenements had been surrendered, the remaining contract was transferred to A&MJ Musolino. Then acting director of Mining Regulations, Paul De Ionno, wrote in a letter to A&MJ Musolino that the company was required to pay a bond of $32,000.

The South Australian Mining Act states it is the purview of the Minister to require a business entering a mineral tenement to also agree to a bond that would pay for land rehabilitation “disturbed by authorised operations”. It is up to the minister of the day as to how they will implement the Act.

In 2006, A&MJ Musolino commissioned Ore Reserve Evaluation Services to complete another legal requirement: a mandatory Program for Environment Protection and Rehabilitation report (PEPR), which is an environmental analysis of an area detailing recommended courses of action.

The PEPR highlighted some low-level but also higher-level concerns for the mine – most notably, damage to the area was historical. For example, the report states some of Mount Gunson’s ore mining pits were rehabilitated decades before, in 1990, but another mining area had been continuously pumped for 35 years. “It is considered likely to take a similar timeframe to recover,” the report says.

The report also outlines problematic “poorly rehabilitated” dumps, such as stockpiles, and the “potential to contaminate groundwater” from certain operations. Some risks of spills were identified, as well as “abundant” erosion of dumps, pits and tailings left from others.

However, there was no new erosion occurring at the time of analysis, with the risk of new waste created being “minor” and “rare”. The risk of pollution from the storage, use and management of chemicals was also “likely” but “negligible”.

One part of the report relates to the mine’s future closure and rehabilitation, stating the overall objective is to progressively rehabilitate the area and make it “aesthetically compatible” with its surrounding geographical context. The long-term goal for the mine, the document outlines, is that it be returned to “pastoral use post-mining”.

There is no indication as to when, if ever, that would occur.

This picture: Graham Armstrong (1988) courtesy of the State Library of South Australia

A subsequent analysis of the area – undertaken by Hornet Resources Assessment Services, published in February 2019 – found there was “insignificant change” to the area since the 2006 PEPR.

“Light scarification of the compacted pad to help promote the regeneration of the natural chenopod vegetation has been considered but advice from the Department for Energy and Mines (DEM) suggests that this may not be appropriate due to ‘long term stability / erosion issues’,” the report states.

CityMag approached Eddie Hughes, the member for Giles, whose electorate includes Mount Gunson, for comment about the area, but we were told “no one” had contacted his office expressing concern for the site.

Minister Koutsantonis says he was similarly “unaware” of an appetite from South Australians for their “taxpayer dollars” to fund the area’s rehabilitation – but this would not preclude the Government from “considering such a measure in future budget cycles”.

The Department for Energy and Mining spokesperson says since 2006 tenement holders “undertook rehabilitation” over parts of the main open-cut areas. This tenement agreement was updated in 2021 to include G4 Pernatty Copper Pty Ltd, the company currently operating onsite.

An expert calls for change

Melbourne-based RMIT University associate professor Gavin Mudd is a sustainable mining academic currently overseeing research into how many mines are in ‘care and maintenance’ and how many have been rehabilitated.

Mudd is also part of Mining Legacies – a national industry watchdog documenting the “people and places that bear the impact of mining”. Mount Gunson is one of two South Australian mines Mudd is worried about.

The Mining Legacies webpage for Mount Gunson includes a series of photographs of the site. Mudd tells CityMag that while attending a conference at Port Augusta in 2012 he made a detour and barrelled down the Stuart Highway to snap some photos of the mine.

The green Mount Gunson water

His images show turquoise bodies of water next to lightning-bolt-shaped cracks in the ground. In the red dusty dirt, rivers of green run into the water. Mudd says his impression back then was Mount Gunson was “certainly not rehabilitated” and not a “well-managed site”.

“For a mine that closed over 20 years earlier when I visited it [just over 10 years ago], you would have expected major rehabilitation works and things like that to have been done,” Mudd says. “[It was] certainly not rehabilitated.”

CityMag visited the site in May 2022 – one decade after Mudd’s photographs were taken. We found mammoth piles of beige and brown rocks – defined as “dumps” in reports – near titanic, green-tinged cliffs resembling tree roots. Bodies of water with salt-crusted edges glow green. The ground pops with rivers of malachite. The site is gargantuan.

We showed our photographs to Mudd. He repeated himself: the site was in dire need of rehabilitation. “It’s still in a very poor condition,” Mudd says. “It hasn’t been rehabbed.”

“Mount Gunson is one of those cases where it demonstrates that we’re not always doing rehabilitation, and that’s basically due to the failure of the companies involved, as well as the actual regulators,” he says. “It’s a classic case study.”

Listen to the Notes on Adelaide episode based on this story, featuring reporter Angela Skujins and RMIT University associate professor Gavin Mudd.

Part of the problem lies in Mount Gunson’s mining history, he says. When the site was used to produce copper cement for the Burra Cupric Oxide Plant for almost two decades, from 1989—2006, the area fell through the regulatory cracks, Mudd suggests.

“It doesn’t follow the normal reporting protocols around all that,” he says, adding “there’s a lot we don’t know about the site.” The Department for Energy and Mining spokesperson says the company produced 50—100 tonnes of copper cement on average annually, for further refining at Burra.

Looking at CityMag’s recent photographs, showing a green-coloured lake, Mudd says he believes fine copper particles (mobilised copper) were in the water, hence the green hue. This is due to the rock being “blasted” by previous mining activities, he says.

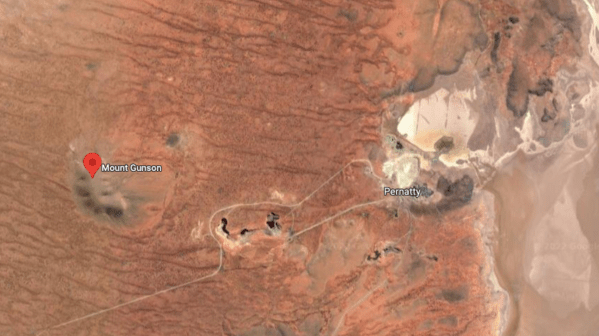

Mount Gunson (left) and Pernatty Lagoon (right). This picture: Google Maps 2022

The 2006 PEPR confirmed there was water contamination, but stated it was “confined” to the pit floor area. The document also says there was no “new source” of contamination, but the area was merely “exploiting one that already exists”.

The massive, mangled cliffs also suggested decades of “significant” erosion, Mudd says.

He estimates it would cost $100 million to remediate the site – similar to the millions suggested by the Mining Minister. But this would just be the start. “It would probably cost more than that,” Mudd says. “There’s a huge amount of work that needs to be done.

“[But], of course, that should have been done and planned and a lot of that executed when the mine closed back in ’89. But they didn’t. They offloaded it to a copper sulphate company and got that going, and left all that stuff for the future.”

The Department for Energy and Mining spokesperson says historical responsibility for rehabilitation of the workings of the site was transferred to the government. Those currently mining the site were only responsible for the rehabilitation of “liabilities incurred” from contemporary on-site operations.

“The Government continues to undertake regular audits and implement and monitor public safety measures at former mine sites, as part of a risk-based approach to the management and rehabilitation of its former mines,” Minister Koutsantonis says.

Mudd says the larger question regarding the site is how representative it is of the entire mining industry, both in South Australia and nationally.

“I would argue that it’s actually very representative, because a lot of mines get put into care and maintenance with the expectation they’ll reopen, and by doing that they don’t have to pay for rehabilitation,” he says.

What can be done (legally)?

Melissa Ballantyne is the South Australian managing lawyer for the Environmental Defenders Office. This is a national not-for-profit centre providing legal advice on public interest environmental issues.

Ballantyne tells CityMag that while her work usually has to do with issues of climate change, her office intermittently campaigns on mining issues. They were naturally interlinked, she says.

This picture: David Washington (2010)

“We give advice, assistance, and have won cases to do with stopping further effects of climate change by stopping big mines, particularly coal mines, [and] stopping big gas projects,” Ballantyne says.

“If you’ve got polluting minerals just leaching out uncontrolled in Pernatty Lagoon… you need to clean up those issues, otherwise you [have] just got uncontrolled pollution into the environment, which causes harm to ecosystems.”

Although no formal complaints had been lodged with the Environmental Defenders Office about Mount Gunson or Pernatty Lagoon, Ballantyne says the site was part of a larger national narrative.

“The overall situation is a bit of a sad and sorry tale of mining companies not properly rehabilitating sites throughout Australia,” she says.

The Environmental Defenders Office has also been fighting for “years” to get community rights inserted in the South Australian Mining Act and other legislation, Ballantyne says, but they’ve been unsuccessful. This means the power mostly sits with the government.

“Unfortunately, the Mining Act doesn’t allow community members to do much in terms of compliance and enforcement,” Ballantyne tells CityMag. “It’s really up to the Department of Energy and Mining to consider it and take what action they think is necessary.”

Under state law, compensation may only be awarded to Traditional Owners or those directly impacted by the mine’s activities, such as in the case of a neighbour. It does not leave room for aggrieved members of the community.

The law also outlines the Minister “may” require the tenement holder to allocate money into the Mining Rehabilitation Fund for the rehabilitation of land deemed not “safe, stable and self-contained”. Failure to pay into the fund can result in a maximum fine of $20,000.

“The South Australian Mine Rehabilitation Fund is a newly created fund established after legislative changes last year, with the Government currently exploring pathways to bolster the fund,” Minister Koutsantonis says.

This picture: David Washington (2010)

And while the Act appears to balance the interests of miners, the community and the environment, Ballantyne says it’s how the piece of legislation is used that matters. The minister is still able to exercise discretion.

“It really is up to the Department of Energy and Mining to either pass a proposal and properly monitor it,” Ballantyne says. “The actions over the years of the Department have been questionable as to, have they given proper consideration to all of the things that are important in a mining operation, not just the operation itself, but have they considered the impacts and care of the environment?”

Ballantyne does not believe rehabilitation costs should land squarely on the shoulders of the government. “The taxpayer can’t cover everything,” she says. Instead, the mine’s operator should allocate funding for work. This means going beyond bonds.

Next steps

University of Adelaide professor of civil and environmental engineering Michael Goodsite believes Mount Gunson – like every mine – should be rehabilitated once resources from the area have been successfully extracted.

Goodsite leads the university’s Institute For Sustainability, Energy and Resources and is involved in research efforts in helping companies and economies around the world get the metals and materials they need while minimising environmental impact. One of these efforts is the Copper for Tomorrow Cooperative Research Centre, where Goodsite is research director.

The Centre aims to “solve the copper paradox,” its website states. This is the conundrum of how to produce the copper needed for a low-carbon society while dealing with lower-grade ores that don’t use more energy and water and don’t produce more waste.

This picture: Graham Armstrong (1988) courtesy of the State Library of South Australia

Goodsite firmly believes copper mines should initially be rehabilitated by those who benefit from them. “In the first instance, [that is] the companies that mine them,” he tells CityMag.

“There should be mechanisms in place (and in some states there are) to help ensure that miners take sites through rehabilitation. If this fails, for any reason, then the system needs to be examined as to [how] best achieve this. Ultimately, the state governments should [then] rehabilitate.”

Goodsite is aware, however, of the multimillion-dollar price tag that comes with restoring a site. In light of this, some mines should take priority over others given the scarcity of resources and lack of public appetite for improvement.

Copper is a significantly in-demand resource – something that is not only key to South Australia’s future but the “common future” of the world, Goodsite says. But innovative technology, not only ample mountains of stock, is necessary for all countries – including Australia – to pursue powering cities through environmentally friendly means.

“To transition to a clean and sustainable economy, we will need more copper in the next 30 years than we have ever mined in world history,” he says. “We need to double current global production.”

The mining technologies we’re currently tracking are energy and water-intensive, Goodsite says, and they produce “ever more” emissions and add to waste. Simply recycling is not enough to meet the demands of a renewable-driven society powered by copper.

But you can extract and produce the metal in an environmentally friendly way, Goodsite says. More importantly, it does not have to be at the cost of progress. “If everyone could earn a dollar improving the environment, we would have fewer issues,” he says. “This would help drive the innovation needed to inform the balance.”

—

This article first appeared in CityMag‘s 2022—23 Future Edition, on streets now.