Of the 46 Aboriginal languages spoken in South Australia, Kaurna is at the forefront of a local language renaissance – but its success hinges on an increase in speakers, teachers and funding.

Real talk at Tauondi Aboriginal Community College

In a classroom at the Tauondi Aboriginal Community College, located in Port Adelaide, there is a laminated map of successful South Australian Native Title claims stuck to the back wall. Seven Aboriginal students sit at grey desks, with notebooks, iPhones and water bottles at hand. Two wear face masks adorned with dot painting designs.

There is nothing exceptional about this classroom – there’s a white board, a too-loud air conditioner and dated carpet – except for the mission being carried out within it. Every piece of ephemera we can see in the room advocates for Indigenous rights and education – including a “Free West Papua” tote bag leaning against the desk.

The tote belongs to Mary-Anne Gale, a white linguist who is leading the Kaurna education session CityMag is sitting in on. “We don’t want this language to die,” says Mary-Anne, a University of Adelaide academic, about reviving the Kaurna language. “It’s been sleeping for long enough.”

It’s 23 March, and we’re at the 49-year-old Tauondi College to learn how Kaurna, the first language academics say bore the brunt of the 1836 colonial invasion of South Australia, is making a comeback.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data show that between 1991 and 2016 the percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people speaking their mother-tongue at home fell from 16.4 per cent to 9.8 per cent. The recently published information also reveals Australian Kriol, a non-traditional language, is the most commonly spoken Indigenous language nationally.

A recent parliamentary report into Aboriginal languages in South Australia states Kaurna – the language used by the 50,000-year custodians of Tarntanya Adelaide, the Kaurna people – is “at the forefront of language revival in Australia”. Out of 46 Aboriginal languages spoken state-wide, exactly half are considered dormant, meaning they are no longer spoken and “may not even be remembered”, the report says. This classroom is where some of that revival is taking place.

“Two girls that are here are former students of mine,” beams Kaurna teacher Cherylynne Catanzariti, who has worked with northern area schools for 27 years. Cherylynne is the daughter of language advocate Cherie Warrara Watkins and is the only Aboriginal teacher leading the class, which teaches Kaurna basics such as a Welcome to Country and the sound system. The Kaurna language has “come a bit of a way” in the time Cherylynne has been working with schools, she says, but “it’s still not where we want it to be. We want it more”.

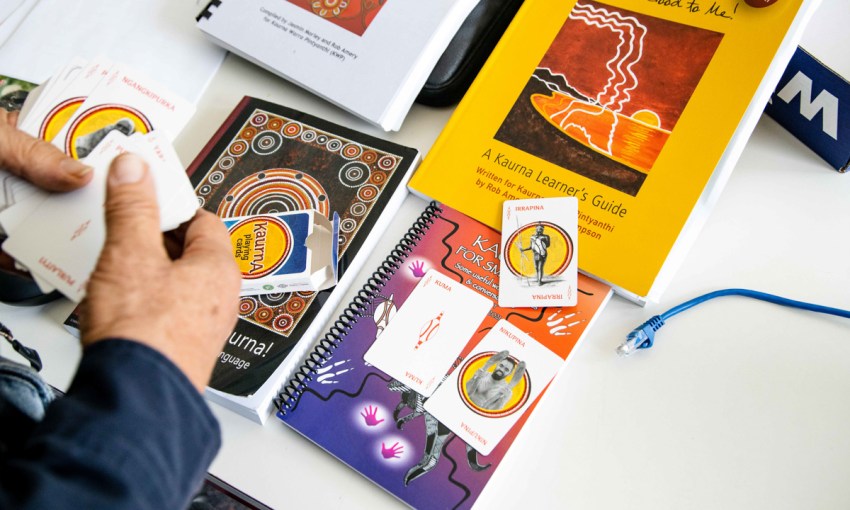

Tauondi educators Rob Amery and Cherylynne Catanzariti

Rob Amery is the head of linguistics at University of Adelaide. He’s helped to revive Kaurna language since the late ‘80s, and he’s also guiding the class. Today, Rob wears an N95 mask and a navy sweater. While peering over the frames of his glasses, he tells the class he’s worked with the Kaurna language for 33 years, “and I’ve worked with Cherylynne’s mum, Aunty Cherie in Brighton College, when it was a city high school back in 1994 all those years”.

Mary-Anne, who is Rob’s partner, tells the students – who range from university undergrads to middle-aged primary school teachers – she’s a University of Adelaide researcher and language coordinator. Her “big thing” also includes producing Indigenous language resources and formally training teachers, such as Cherylynne.

During her introduction, she also issues a stark warning: two of the 26 recent Kaurna language graduates have died. More graduates are needed to keep the language alive.

—Mary-Anne Gale

Time isn’t on the teachers’ side, either, as Mary-Anne and Rob are nearing the end of their careers. “Mary-Anne and I are heading towards retirement and trying to impart this knowledge we’ve accumulated over the last 30 years,” Rob says. Cherylynne says she wants to put her feet up soon, too.

As the lesson gets underway, the quintessential classroom getting-to-know-you activity is performed, as the cohort is asked to introduce themselves and explain their reason for attending. Two bubbly sisters, Pamela (who goes by Pam) and Letisha (who goes by Teesha) go first. They’re the students Cherylynne taught many years ago.

“I did go and do teaching, but I’m not entirely sure about that now,” Pam says. She’s wearing a black Adidas sweatshirt, her hair pulled back into a tight bun. “Me and my sister have just started a business, so maybe we can put that under our business?”

Teesha is completing a University of Adelaide science degree, and wants to connect western science and Indigenous land knowledge through language. “I want to bridge the gap,” she says, smiling. She’s also brought along her boyfriend, Aaron, who is studying to be a high school history and psychology teacher.

“I thought I’d come here today and thought learning about the language would help [me] be able to integrate it into my classroom,” Aaron says. He posits the idea of sticking Kaurna phrases on paper to the walls and asking his students to introduce themselves in language.

This possibility excites Cherylynne, who says she taught young kids the building blocks of Kaurna through nursery rhymes like ‘Incy Wincy Spider’. “It’s just starting them off and preparing for the language,” she says.

An older gentleman called Wayne introduces himself as a teaching assistant at Forbes Primary School, in the inner south. He says there are 45 Nunga (Aboriginal Australian) students at his school, and wants to use Kaurna to give them a sense of identity. Despite some who “don’t know where they’re from or who their mobs are”, he thinks teaching Kaurna to students would be more beneficial than a language like Indonesian, which is offered at Forbes and is one of the 12 languages other than English taught in South Australian state schools.

About 25 minutes into the introductory session, Mary-Anne shares with the class her hopes for the future of Aboriginal language education in South Australia. It’s been four days since the Labor Party won the state election. “We’re hoping that the new Minister of Education will be more sympathetic towards Aboriginal languages, so maybe he will help us get recognition for what you guys are studying and just create these pathways for people who just want to be a language teacher,” she says.

South Australia’s new Attorney-General and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Kyam Maher, is an Aboriginal man with Tasmanian heritage. He grew up in the Mount Gambier region, home to the Boandik and Ngarrindjeri people. “Languages are an important expression of identity, and with the teaching of language necessarily comes the teaching of culture,” Kyam tells CityMag later, over the phone.

While in opposition, Kyam completed one of Mary-Anne’s University of South Australia Pitjantjatjara language programs. He wanted to communicate with people while on their Country, he says, “and although I’m not fluent, [I] can understand and speak a little bit – and that’s been an invaluable thing”.

The United Nations General Assembly declared 2022—2032 the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, with the aim of highlighting the plight of at-risk languages and encourage their preservation, revitalisation and promotion. That aforementioned parliamentary report regarding spoken Indigenous languages in South Australia also came with six recommendations to turbo-charge the use and teaching of languages locally.

When pressed about when the Malinauskas government will implement the six recommendations, Kyam says the government’s progress towards developing an Aboriginal Voice to Parliament and Treaty would engage with these issues.

While the State Government progresses towards these goals, Kyam believes non-Aboriginal people can play a role in advocating for culture. This means learning the language. “It shows that you have a desire to want to understand the 40,000-plus years of continuous culture that has occupied the land that you’re on,” he says.

To rescue a dying language from colonial destruction is an enormous feat, but, as CityMag can see in this Port Adelaide classroom, it will be victory won through minor achievements. After an hour of classroom chatter and presentation via PowerPoint, students have begun to fidget and doodle. Lunch is now on the room’s collective mind. “The canteen’s not open but they have a sausage sizzle downstairs,” Mary-Anne says.