Elder Major ‘Moogy’ Sumner has been involved in numerous high-profile repatriations of Aboriginal remains. He’s about to embark on his most personal and poignant one yet.

Bringing Dad home

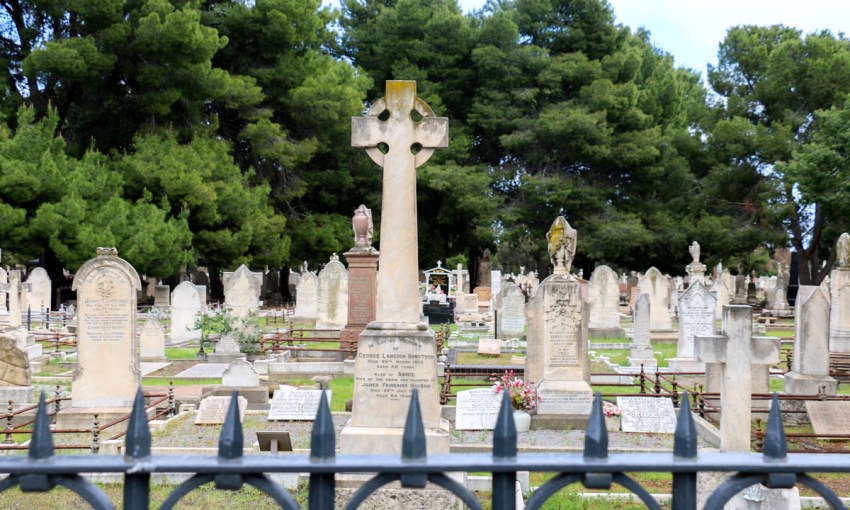

Sitting on timber benches out front of the West Terrace Cemetery, looking at mammoth tombstones flush with curlicues and wrought-iron trimmings, Uncle Major ‘Moogy’ Sumner describes his dad, Colin Rex Sumner, as “no one special”.

“He died up in Andamooka or Oodnadatta, that way,” the senior Aboriginal man tells CityMag.

“We didn’t even have money to bury him. That’s why he is in a pauper’s grave now.”

A plaque at the mouth of the 13-hectare State Heritage site details the history of the cemetery. It also describes how, just as for those who exist on this mortal coil, equity isn’t always available to everyone in death.

“Grand and imposing headstones were mainly confined to the prominent and wealthy,” the plaque says. “Those unable to pay for a funeral suffered the anonymity of an unmarked grave.”

Though he may not have been a high-profile individual, Colin Sumner matters to his son. The now 73-year-old Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri Elder cannot shake the spectre of his dad, whose bones lie somewhere in the state’s oldest cemetery.

“I can’t stop thinking about him because my brother’s name is Colin. He is named after my father,” Uncle Moogy says.

“He’s always there.

“And his spirit has been sending me a message to take him home.”

Uncle Major Moogy Sumner

THE PRESENT

We can’t find Colin Rex Sumner’s grave. It’s 12pm on Tuesday, 27 September, and we’ve been trudging through the city’s West Terrace Cemetery soggy grounds with Uncle Moogy for 20 minutes. But the Elder has connections. He whips out his phone and makes a call.

Five minutes later, an Adelaide Cemeteries Authority employee with a cropped brown haircut and a high-vis vest greets us. A higher-up has asked him to help us locate the grave of Colin Sumner, who was buried at the 185-year-old graveyard in 1967.

We show our guide the grave’s location on the map we have on our phone, but the worker is stumped. He doesn’t know where the spot is. When we eventually get a printed-out version of the map with coordinates, the employee says – almost apologetically – Colin Sumner could be buried in “one of four” possible graves.

We walk towards the grave’s supposed location, on the southern side of the cemetery, near a low-lying wall and a willow tree. We see large swathes of grass with vague rectangular outlines, but the ground is otherwise not demarcated. There are only a few headstones, even fewer legible inscriptions. Some of the graves have caved-in concrete roofs, exposing twisted plant roots and dirt below.

Colin Sumner is buried somewhere here

This pocket of the cemetery differs starkly to the northern mound where we originally met Uncle Moogy. Bucking onto West Terrace, the area where we started our journey has large swaying pine trees overlooking granite angels, carved roses and marble tombs. People with prominent names, like Bonython, are laid to rest there, their memories etched deeply into the city’s consciousness through the simple legibility of their names.

Where we are now, there’s little signifying who’s buried below.

After conferring with the printed map for 15 minutes, we conclude Colin Sumner’s grave is somewhere in the galaxy of dirt in front of us.

What we do know from the printed-out map is Colin Sumner is buried at the top of a stack of four coffins. The earliest coffin was interred in 1882.

This is a pauper’s grave – paid for by the State Government. At this cemetery alone there are 12,000 maintained through government support.

Uncle Moogy, who is calm and quiet throughout the ordeal of finding his father, eventually breaks his composure. Underneath his painted-up ochre face – donned for a formal event earlier in the day – he furrows his brow. This senior Aboriginal man wants to mourn his dad.

More than that, he wants to repatriate the remains of his father back to his spiritual home, the Coorong. Once there, he will conduct a smoking ceremony to put his dad at ease.

“It’s been on my mind for a long time – years. About getting them and taking them back home,” Uncle Moogy says.

“To a place called Long Point. The traditional name of it is a Dapung Talkinjeri, and that was where he was born.”

An angel protecting someone’s eternal slumber

THE PAST

Before assimilation policies divided and displaced Uncle Moogy’s 12-member family, with the kids moved from Raukkan to Millicent in separated boys’ and girls’ homes, the Sumners lived a humble life.

Uncle Moogy’s favourite memory of his dad is when they would go “spotlighting” for rabbits with a horse and cart. Spotlighting, Uncle Moogy explains, is when you chase rabbits with a light.

“You used to get the battery out of the car, put it in the cart, hook the spotlight onto that, and then get in the horse and cart and go around the paddocks and that with the dogs,” he explains.

“That would be our dinner that night. My mum would cook it; make a stew out of it, or bake it.”

The ochre around Uncle Moogy’s eyes cracks as he smiles. His mind quickly turns to another memory. When Uncle Moogy was 19, his dad died. “I was a young man,” he says.

Uncle Moogy has long been involved in various Kaurna repatriations. In December last year, Uncle Moogy and Kaurna elders Jeffrey Newchurch and Madge Wanganeen led the smoking ceremony and interment of 130 Old People at the purpose-built Wangayarta cemetery in Smithfield.

Uncle Moogy overseeing 130 Old Peoples’ remains at Wangayarta

That particular experience ignited a decades-old desire for Uncle Moogy to repatriate the bones of his dad back to the Coorong, the Country of the Ngarrindjeri people. At this cultural event, Uncle Moogy struck up a friendship with former Adelaide Cemetery Authority CEO Robert Pitt, who indicated he would try to help him get those remains home.

CityMag sent questions to the Adelaide Cemeteries Authority about whether their new CEO, Michael Robertson, had a similar desire to help, but we did not get a direct response.

Instead, a spokesperson sent a statement, saying the applications to exhume and repatriate remains are considered and approved by the Attorney-General’s department, and the organisation is “supportive” of anyone wanting to repatriate remains.

“In 2017, we helped to return Miller Mack to Raukkan,” the spokesperson says, referring to the repatriation of an Aboriginal veteran.

“We have also worked closely with the Kaurna community to repatriate Kaurna Aboriginal ancestral remains to rest on Country at Kaurna Wangayarta Smithfield Memorial Park.”

Unlike the Old People at Wangayarta, Colin Sumner’s bones have not been disturbed through colonisation, but there is tragedy in the story of his death. Uncle Moogy’s dad was allegedly murdered in a bar brawl in a town in the state’s far north. The perpetrator was never brought to justice, Uncle Moogy says.

We ask why he didn’t agitate for justice at the time, and he looks at us patiently. He was a 19-year-old Indigenous man. “At that time, Aboriginal people didn’t have much of a say,” Uncle Moogy says.

CityMag sent questions to South Australian Police about the status of the 55-year-old case, but they couldn’t provide an update before our publishing deadline.

Update: Half an hour after publication South Australian Police informed CityMag the Major Crime Investigation Branch was unable to locate information regarding Colin Sumner.

They recommended Uncle Moogy or his family could contact the Coroner’s office to locate records.

As trucks roar down West Terrace and rain whips around us, Uncle Moogy says he believes his father’s body was brought to metropolitan Adelaide for assessment and autopsy. The family “didn’t have any money to take him home”.

He says his father has been sending him spiritual messages to return to Country.

“His spirit wouldn’t be resting,” Uncle Moogy says.

“He’s in a place here where he shouldn’t be.”

Uncle Moogy looking for his dad

THE FUTURE

According to the Adelaide Cemeteries 2022-23 price guide, exhumations at West Terrace cost $7500. A 99-year burial or vault interment fee for an adult is also $3350.

Uncle Moogy is in the process of finding the right grants, and rubbing the right political shoulders, to repatriate the remains of Colin Sumner. He’s aware it would be an expensive and onerous undertaking, as he needs the signed approval of all his siblings, but he wants to push through. He recommends others whose families reside in pauper’s graves to do the same.

“Take them home,” Uncle Moogy says.