Rather than focussing on short-term solutions like sanitiser dispensers or automated pedestrian crossings, University of South Australia’s architectural historian Julie Collins says we need to consider long-term urban planning solutions to keep people healthy and happy.

How to design a pandemic-proof city

SPECIAL REPORT: COVID-19 ADELAIDE

“When we hear the word ‘health’, now we think of some of the temporary solutions which have been put in place, such as the opening of windows in buildings and hand-sanitising stations at the front of buildings,” UniSA architectural historian Julie Collins tells CityMag.

In order to ensure we’re prepared to weather any future pandemic, Julie adds, we also need to consider “accommodation for the homeless, the need for quarantine facilities and isolation hospitals, and also the support for essential industries and manufacturing”.

If the COVID-19 news cycle is affecting your mental health and wellbeing, call the SA COVID-19 Mental Health Support Line on 1800 632 753.

A recently published paper, co-authored by the academic, examines how tuberculosis, another deadly and infectious disease active in the 19th and early 20th centuries, impacted Adelaide’s built environment.

The paper found the virus’ impact on postcode 5000 and surrounds was long-lasting.

And because there was no cure, treatment relied on health and design experts harmonising to bring about solutions.

Some artefacts of this healthcare chorus still exist today.

‘Nunyara Sanatorium for the Open-air Treatment of Consumption’ (1910). Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

“Because there weren’t any treatments, there weren’t any vaccines until that mid-20th century time,” Julie says. “The only way they could deal with it was really to take people with the active disease, and treat them in sanatoria.

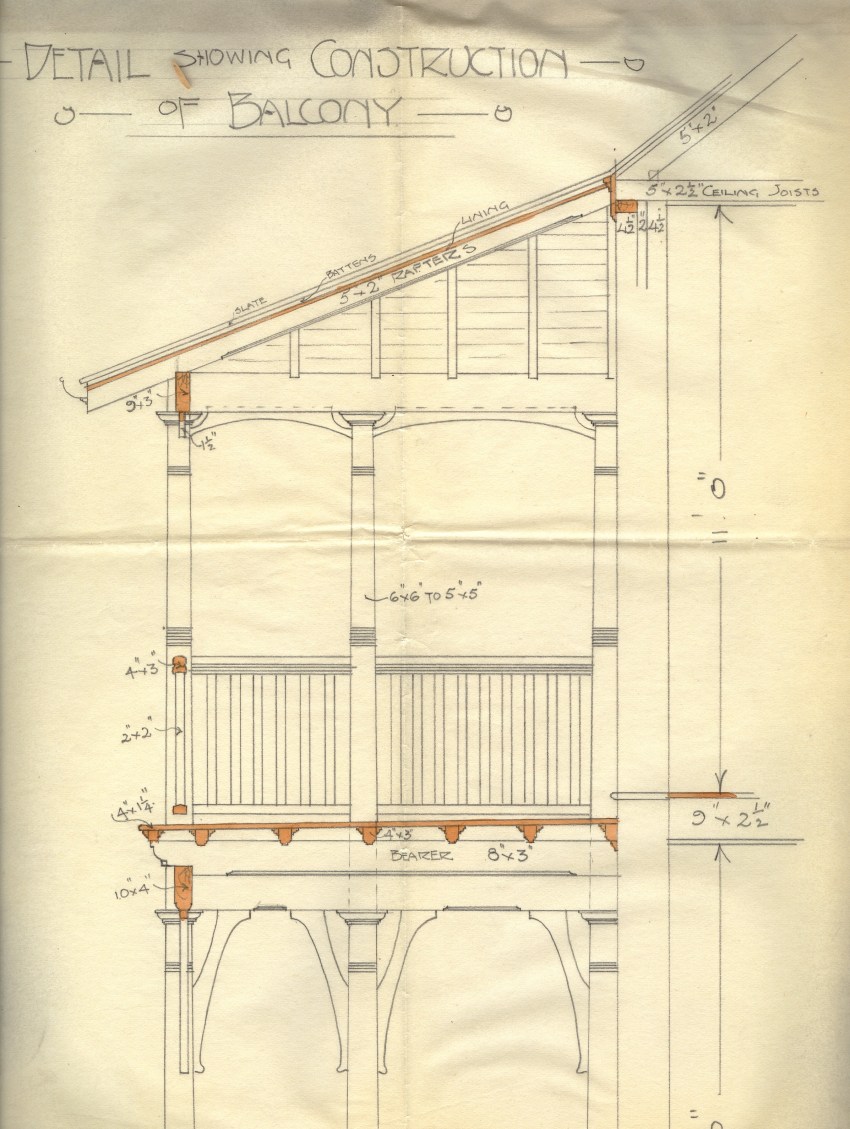

“They went there, and they stayed there, they were given nutrition and rest and exercise and looked after. And these sanatoria had individual kind of rooms for people, they had large openable windows, balconies for people to rest on, views over nature And [another] part of the cure was exercise.”

Outdoor sleeping was recommended healthy behavior for those suffering from respiratory problems, such as tuberculosis. Courtesy of the Milne Collection, Architecture Museum, UniSA.

Although these sanitariums didn’t totally cure patients with tuberculosis (TB), they provided the opportunity to isolate cases from the general community, just as we now quarantine interstate travellers or suspected and confirmed local COVID-19 cases.

Some of the TB medical centres still stand today, such as Nunyara, nestled in Belair, which is now a conference centre.

When we ask Julie what learnings could be applied from this public health crisis, she says more established quarantine stations should be set up to isolate and treat patients.

“Torrens Island was used in the 1870s to 1960s [for quarantine] and it’s still got some remnants of some prefabricated timber combination buildings, which were erected quite quickly,” she says.

“We’ve moved to the quarantine hotel, but there’s a lot of calls for purpose-built and designed ones.

“I think it’s really important that airflow, ventilation, spacing, as well as access to exercise to cater for the wellbeing of those who are being forcibly contained or confined there, it’s quite an important aspect, which is another thing which COVID-19 has once again brought up, which we thought was a completely forgotten building type.”

Aside from clinically treating an illness with pharmaceuticals and machinery in a hospital or treatment centre, the mental health impacts of a virus are just as important and should be considered, she says.

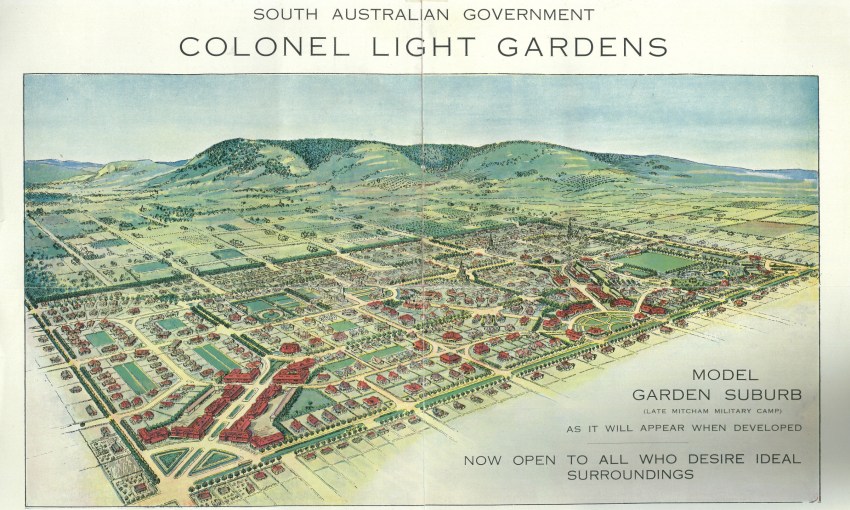

Colonel Light Gardens birdseye view (1921). Courtesy Architecture Museum, UniSA

Green spaces hold a lot of power in supporting peoples’ mental wellbeing.

—Julie Collins

“Access to green and natural spaces and public parks and gardens is really important, but it depends on suburb or land use,” Julie says.

“The idea of the garden suburbs was something which emerged [from the paper] and that was all about housing improvements, green space provision, street layout, and one of the suburbs which is now 100 years old, Colonel Light Gardens, which opened in 1921, was what was called a garden suburb.

“It had as its aim ‘improving people’s lives through healthy environments’. Even though that was 100 years ago, it holds some really good lessons for future design.”

Another big architectural takeaway that could come in handy is a suggestion from 1859 novel Notes On Nursing, penned by historically acclaimed nurse Florence Nightingale.

“She suggested completely tiling the outside walls of a house, which would lead to improvements not only in the dryness and healthiness of the home, but also she was suggesting it could be washed down with fire engine,” Julie says.

“So that was going to the full extent of hygiene.

“A lot of those modernist white box, hygienic, modern buildings… The plain surfaces came out of a desire to wipe them down to keep them clean to eliminate dust.

“Those things are really fascinating, in that design can actually have some of its roots in creating a healthier society.”

If the COVID-19 news cycle is affecting your mental health and wellbeing, call the SA COVID-19 Mental Health Support Line on 1800 632 753.