As CityMag celebrates 10 years of informing our city, we reflect on how it was created. Co-founders Farrin Foster and Josh Fanning spoke with us about the ambition it took to start a magazine in the first place, and how by doing this, they actually changed the city for good.

Reflections from the founders

CityMag: How did you come up with the idea for CityMag?

Josh: The idea probably came out of being sick of seeing other people benefit out of the tide we were creating. It’s a big thing to say. But I think a lot of the time when you’re a journalist, you’re writing stories about other people and that helps their business and other businesses start and so on. And we had two magazines, Merge and then Collect. Collect was really successful-ish.

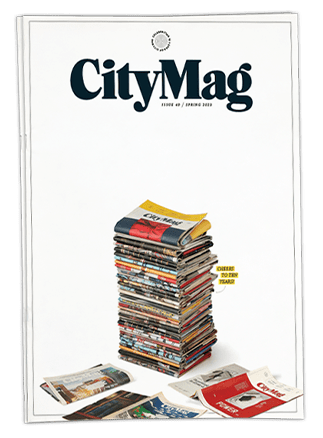

This article first appeared in our 10 Years of CityMag, Spring 2023 edition, which is on streets now.

Farrin: I felt like one of the things about Collect’s success was it was not at all successful in Adelaide. And it was successful in its own way, but exhausting, because the business model was unsustainable, and we couldn’t pay ourselves or anyone else. So, to me, CityMag felt like a scalable way to bring Collect to Adelaide to bring the stuff that we’d learned from those first two magazines into a publication that spoke to our city.

J: We just wanted to tell great stories about Adelaide and couldn’t see that in the press. That was the loose idea behind Merge. And I think Collect was just more mature, grew out of Merge and was more about ‘Hey, Adelaide is fine, but also leaving Adelaide is fine and great’. So how does Adelaide compare to anywhere in the world? The idea for Collect was, well, you don’t live in New York, you live in a borough in that borough, you live in a neighbourhood in that neighbourhood, you live in a street, and some of Adelaide streets are as good as anywhere.

F: Yeah, and I think that’s why Collect was successful because, I’m sure you’re too young to remember this, but there was a real, cultural moment where people realised that supporting their neighbourhood, economically but also socially, could affect change. And in a time when everyone feels very powerless because of the sweep of catastrophes like climate change and also The Digital Age ending all the systems, the ability to proactively do something and see results was very sticky. We still looked at CityMag as placing Adelaide in conversation with the world.

J: I think the way that Collect grew to an international magazine, CityMag was about coming home, and really it was about a frustration with us living in the city.

I was a journalist running a business and that’s a bad idea. It’s a really bad idea. I’ve had a lot of entrepreneurs say that naivety is integral, like if you knew how hard it was going to be, you just wouldn’t start.

[But] the lofty goal of CityMag was to author Adelaide’s story in a way that like Seinfeld and Friends and Frasier told the story of small footprint living. This idea of high-density living, which is so foreign to a suburban nation like Australia — how do you give up a double door garage in the front yard? What do you get? And so CityMag was about — well, this is what you get: You get to know your barista, you get to know all of these people then you walk out and you have a great life.

I would interpret Farrin as diversity, because that was the main thing I saw that you wanted to do is put different people on the covers of magazines, put different people on the pages.

F: I mean, when you talk to different people, you hear different ideas they have maybe if we don’t just ask the same people what they think the city should become, it will become something else.

The first ever CityMag cover. Nice stuff CM team

C: What were those first few years/editions of CityMag like?

F: The making those additions though, was pretty wild and a real highlight of my life because we only did print, we did quarterly and we also ran a cafe, which was [an] art gallery and a co-working studio as well, inventively called Magazine Gallery and Josh also worked at the Mercury Cinema [as marketing manager].

I think what we tried to do was, every quarter, I would get one week where I didn’t have to run the cafe and I tried to write most of the stories in that week. And I’d like produce them in between me making people sandwiches the rest of the time, and I’d run around with like, one or two photographers, madly interviewing people. But we really would just do whatever we wanted. We didn’t have money or staff — it was just you and me.

C: How did you juggle all of those things?

J: I think age — has to be.

F: I cried a lot. All the time. I hated running the café, but we just needed to pay rent. I think we thought a magazine store would be good.

J: We just thought ‘Diversify your business’.

F: Yeah, try everything

J: We never read any books about business ownership — just entirely non business focused.

I think it was just ambition. There’s that cliche ‘Youth is wasted on the young’, and I really felt my interpretation of that was just, you’ve got to try really hard and do things, regardless of money and regardless of outcome, and regardless of fame.

I think that just flows through into business and ambitions and trying to see what you can do and what you can change. You know, we did connect with the government, we did create small bar licenses with Udaberri, we did through Collect design Clever Little Tailor, which was the second and really the official pilot of this special circumstance license. So we did feel like we were changing history.

What we wrote about would get picked up by politicians, which would go down to underlings, which would come back to us, which would go out to our network, which was a status quo. And that’s what we tried to do was change the status quo.

F: One of the things we did have in common is I don’t want to have any regrets for not trying my very, very best. So, I will like completely throw myself at something. And if it doesn’t work, I’ll be like that’s fine, but if I didn’t throw myself at it, then I would be very regretful. So, I was like ‘Oh we’re starting a magazine, okay, I don’t need to sleep’.

J: But it was Martin Sharpe, who was the creative director [for Oz magazine], which is just a fancy word for artist and designer. He said ‘I don’t know why young people today aren’t doing what we did in the 60s’. But I guess that’s the same as saying ‘Youth is wasted on the young’. I guess it’s the same as saying ‘Why would you complain about Adelaide staying the same, if you don’t stay and change it?’

I took that seriously and just thought, ‘Yeah, actually, people can, we can change things.’ That was the naivety, I guess. The first naive moment became the unfortunate thing, And the thing that was the carrot in front of us both was like, we were changing things just not necessarily for ourselves.

C: What was the process from building up a magazine by scratch to having it actually take off?

J: Café got closed. Well, it didn’t get closed down. He just said that you needed to keep the dog out of the food area. And I refused, I said, ‘We’ll close the café’ because we must have had a conversation that [CityMag] was going so well slash out of control, but also a huge opportunity. But oh my god, how are we going to survive if we do seven things? Let’s close the café and do one thing. Let’s turn the space into a co-working. Simple business lessons that we made very complicated as creative minded people.

C: What memories do you have of that time period?

J: Cockroaches

F: No, I was terrified of cockroaches and rats, we were on Hindley Street, the cafe. So, there was not a single crumb that was left on the floor or on a bench. Every piece of crockery and cutlery was sealed into an airtight container. Like nothing could be touched, and I disinfected everything every morning and every night. So there was nothing for cockroaches and rats. And then when it became a co-working space, I was like ‘Eh’.

[But] it was a really nice time. A lot of people who worked in the co-working space were contributors to CityMag, but also digital got off the ground. Lauren [the design director], redesigned the grid of CityMag, so made some really fundamental changes to how it worked as a magazine.

J: But I guess we just were so committed that Farrin and I were reading about magazines and reading other great magazines. So we were finding all of the tricks or the simple things you should’ve done already. And so we started back, retrofitting, we had interns, we had more help, and we weren’t doing everything ourselves.

[At this point] we understood editing and a tone of voice and a way of writing that was more exciting than ‘He said, she said, on this day, facts, boring’. Instead of past tense, which is news, we brought it into present tense. So it was ‘They say’ and ‘Says’ and the way we would write with lots of alliteration and lots of fun and energy. Everyone who survived [at CityMag] as a writer, got the tone of what we were trying to do.

F: That’s what a good freelance journalist does is adapt to the house style of the publication they’re writing for, and it’s our job to set the style to suit our audience.

And that was like a real amazing era. They didn’t have to come in because they were freelancers, but they have desks if they wanted to come here.They wanted to come in and it was a really nice place to be even when Josh and I were arguing.

But we also still managed to have a really good time. And we all worked really, really hard. But there’s something about the comradery. I feel like everybody wanted to do the same thing. They felt like CityMag was a tool to achieve something they cared about and it was nice to do that together. Also, the deadline parties were really, really good.

New here? Sign up to receive the latest happenings from around our city, sent every Thursday afternoon.

C: How does it feel to see CityMag still grow and evolve?

F: I feel like it’s now carving a path beyond us, which is a good thing. My editorial sensibilities, I think, laid a good foundation for CityMag, but my interests were moving in a different direction to where the magazine needed to. It needed to continue building on what it had already created and I wanted to write about other things.

J: That is what happens with creative people and a magazine’s not really allowed to do that. Once you’ve got a brand, and you’re known for something, that’s what readers get familiar with but also advertisers. So if you want to evolve, and that’s probably part of the story of the three mags is they all evolved, but you’re going to kill one to start another one. Whereas if CityMag’s going to live forever, and I think it can, it had to stay the same in a way. That’s when I think editors do move on, don’t tell what the editor of Vogue that though.

F: But I’m glad that it has been able to continue to grow and evolve. And I just feel like it’s not really for me to have an opinion on anymore. But yeah, every now and again, I think about it, I’m like, ‘Wow, I can’t believe we actually did it’.

This article first appeared in our 10 Years of CityMag, Spring 2023 edition, which is on streets now.