Conversations about shaving

Words and Illustrations: Anthony Nocera

At the churn-and-you-miss-it pace of modern media, writers are given just a few hours to provide opinions on the issues of the day.

In this illustrated series, ‘Responding in Real Time’, Adelaide writer Anthony Nocera instead provides a thought-out hot take on a lukewarm topic – responding to the world as he sees it, in real, human time.

This week, Anthony considers Gillette’s ‘The Best Men Can Be’ ad.

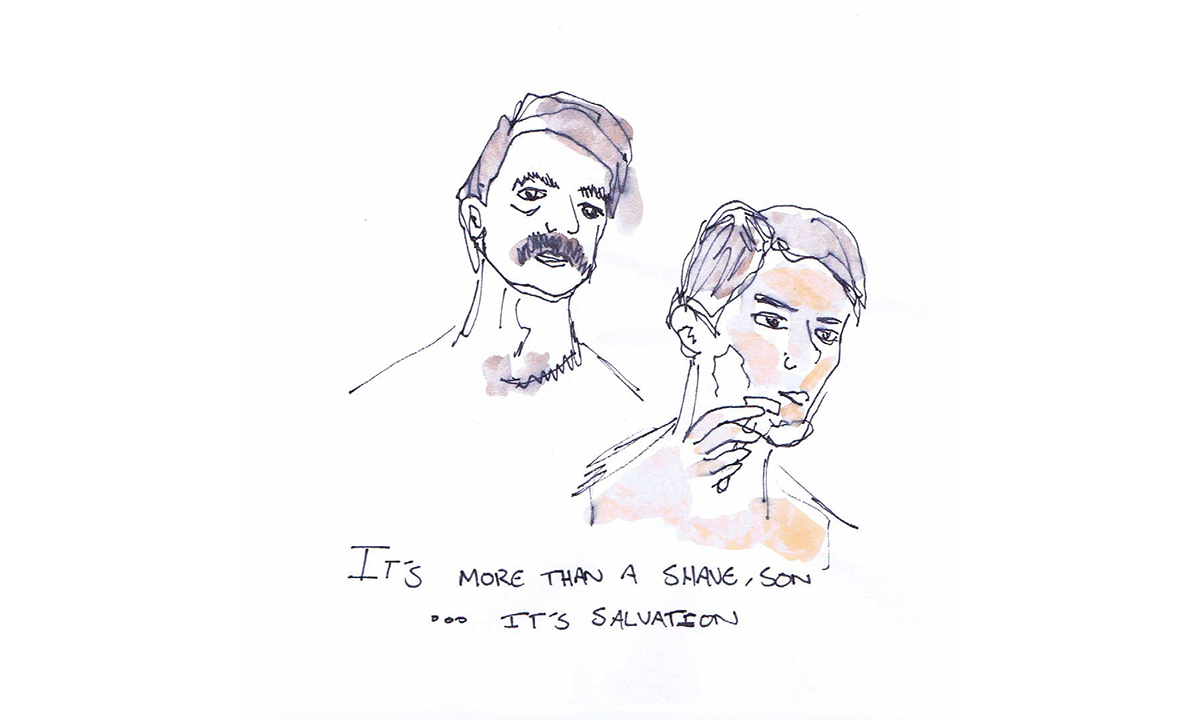

I’ve been having a lot of conversations about shaving lately, I’ve been thinking about it. The art of it, which I guess was the point of that Gillette ad.

There is an art to shaving, my dad said, while stood next to me at the sink when I was eleven or twelve, putting shaving cream on even though he didn’t need to. He handed me a Gillette Sensor Excel and said “Anthony, Anthony, Anthony, you need to shave with the grain of your hair so that you don’t cut yourself.” He slowly dragged the razor across his skin and I followed.

“You’ll always feel better after a shave,” he said. “Your skin feels cleaner, the hair gets itchy if it gets too long. Always be clean shaven if you can.”

I soon realised that I could get a much closer shave (and therefore shave less often) if I shaved against the grain of my hair, and went on to spend the best part of my teens hacking into my face.

In a bold bit of experimentation, I used that same razor to shave against the grain on the skin of my balls and my arse and streaked blood Kill Bill style across the bathroom floor.

I’ve never shaved my face or my balls with anything else.

October 2015: A conversation in a phone store in Norwood

He shuffled into the store once a week. He was a sixty-year-old man with papery skin that was once white but had faded grey, almost as if you could see the bones, the muscles, the gristle pulsing under it. He had a thick southern American accent and one of those obnoxious names that only exist in army movies: Jack-knife, Holster, Scythe, Brian… I don’t know. But he wanted a phone that was sturdy. Hard, Tough. Like his army-issued phone that was all yellow and dark green two-inch thick plastic that I was 90 per cent sure he wasn’t allowed to have.

“I’m sorry, we don’t sell anything army issued. Because we are not… the army.”

“Well in my day to day life, I trade in a lot of mud. I need something that can handle mud.”

I pictured him on the side of the road selling sacks of mud to other stupid people.

“Wouldn’t it be easier to trade in a lot of dirt and then let people wet it themselves?” I said, laughing.

“You know we had a funny man like you in ‘Nam. They shot him first. He was too busy laughing to dodge the bullets.”

“Oh,”

“I need a phone that isn’t going to laugh in the face of death.”

“I don’t know if we have those.”

“You know, in ‘Nam they made us be clean shaven every day.”

“Oh yeah, I prefer to be clean sha-“

“I had to shave every morning the exact same way. I still shave that way to this day…”

“Wonderful,” I said, “so about the pho-”

“A single blade, no cream. Cold water. Against the grain, for a closer shave. I need a phone that can handle a rough shave like that… not one of these modern razors that glide across the skin. It needs to drag.”

“Against the grain, for a closer shave,” I said, laughing, “that sounds like an ad for a razor.”

“You would’ve died in battle,” he said.

December 2018: A conversation in the supermarket

A few months ago, I bought a bamboo toothbrush because I felt like I wanted to be a better person. It was wrapped in three types of plastic and I bought it from Woolworths. The brand was emblazoned in all caps. It was nine dollars. I bought it and my boyfriend said, “Do you want to get a backup plastic one just in case that one is shit?”

“No, absolutely not,” I said, “there’s no backup planet! There’s no need for a backup toothbrush.”

“Okay but I’ve hea-“

“Look at the packaging,” I said. Shoving the toothbrush in his face, “what do you see?”

“A panda wearing sunglasses.”

“Exactly. It could be because he’s a cool and hip panda. But it could also be because of global warming caused by people like you.”

“But I’ve hear-”

“What do you think this panda is saying? He’s probably saying, I’m melting, save me!”

“Okay,” he said, shrugging. I walked ahead of him in the supermarket aisle like I’d won. Like I’d taught him something. “Do you need razors?”

“Oh yeah,” I said, grabbing a pack of Gillette Sensor Excels.

“Don’t they have biodegradable razors?” he asked me, laughing.

“Not yet,” I said, very seriously, “but I’ll do my duty and buy them when they do.”

January 2019: Worldwide conversation starter

Gillette released an ad that challenged men to ‘be the best they can be.’ Encompassing street harassment, bullying and violence and referencing the #metoo movement. In the process, the brand committed $1 million to helping programs that educate men to be better. The brand was brought by Proctor & Gamble for close to $60 million in 2005. Last year it was valued at over $17 billion.

March 2019: Conversations on stage

Ulster American was staged as part of the 2019 Adelaide Festival. Written by David Ireland, it’s a play that sees two male theatre-makers, one up-and-coming male director and one famous Hollywood actor, meet with a lauded female playwright the night before they’re to begin rehearsals on her new play.

As the night progresses, the façade of #metoo and liberal virtue signalling is pulled away to reveal savagery across all three characters. It was a play about bad men, bad women and bad behaviour, but above everything else it was a satire of various contemporary modes of performance.

The fictional theatre-makers prepared to stage a work of theatre and performed their virtue for each other. The set sat contained in the middle of the Dunstan Playhouse stage, with the black bones of the theatre on full show behind it. This was a play screaming about the nature of artifice and the level of it we live with every day. As you laughed, or didn’t, or felt bad for laughing at the men who joked about rape and the three characters who continuously pushed the boundaries of polite decency, the theatre stared blankly back at you.

Ulster was a play about a lot of things. But what struck me was how it stripped the characters bare to the point of savagery. It ripped back all of their layers of artifice until it got to the core of who they were, we are. It said, everything we do is theatre, we perform every day… even the good stuff. Especially the best parts of ourselves.

January 2019: Conversations on page

In her column in the Sydney Morning Herald, Clementine Ford defended the ad, writing the following:

Using the work of #MeToo to sell razors to men – or at least, to the women buying them for their partners and sons (at a fraction of the cost of those they’re buying for themselves: #pinktax) – is a cynical exercise. Messages of social change spruiked by giant conglomerates like this look good on the surface, but they’ll always be contradicted by the fact that capitalism and its worship of mass production fuels the very things they pretend to take “corporate responsibility” on.

But, in the context of the culture we live in and the reality that advertising forms a hugely influential part of it, ads like this can inspire some small amount of change, even when they sit alongside the uncomfortable realisation that it’s the audience and not the razor that’s the product being sold.

In the essay Globalizing Capitalism and The Rise of Identity Politics, Frances Fox Piven writes:

[I]dentity politics fosters lateral cleavages which are unlikely to reflect fundamental conflicts over societal power and resources and, indeed, may seal popular allegiance to the ruling classes that exploit them. This fatal flaw at the very heart of a popular politics based on identity is in turn regularly exploited by elites.

Reading Clementine’s praise of the Gillette ad felt a lot like such exploitation by elites was working. The subsumption of identity inherent politics in capitalism was not only being accepted by the left, but openly championed as a marker of success. As a marker of things changing for the better, as opposed to exposing a fundamental deficiency in the way the media has positioned its critique.

It’s easy to see the ad as progress – to buy a razor in place of doing the shitty ideological work required to be moral. The Gillette ad felt a lot like giving up – like the appearance of progress, like a performance, like it was doing more harm than good.

It felt like shaving against the grain. I thought about my dad standing at the sink and me ignoring him anyway. I thought about my blood shooting across the floor.

December 2015: Another conversation in a phone store in Norwood

Jack-knife shuffled into the store again, sweating and breathing heavily. I got him a cup of water. I grew to like him and his camo pants, mainly because I never had to sell him anything or do anything other than stand there, looking like I was working, while he was talking about mud.

“Water, yes… I haven’t experienced heat like this since ‘Nam.”

“Really?”

“Yes. It’s a dry heat. The sun beats down on your back and on the top of your head. Pierces you like a bullet.”

“Have you been shot?” I ask.

“Not me, but you see things when you’ve lived a life like mine. When you’ve been to ‘Nam.”

“You have such vivid memories of the war, it must’ve be-”

“I didn’t fight in the war,” he said

And it occurred to me that maybe this man hadn’t actually ever been in the army but was a particularly aggressive gardener who just regularly holidayed in Vietnam.

“Oh it just sounded like you fou-“

“Well, that’s the trouble with jokers,” he said, “you don’t pay close enough attention. Any progress on getting me a sturdier phone?”

“No,” I said, looking off into the distance for a second. “None that could handle mud. None that could handle a rough shave.”

And he shuffled off back into the sun.

December 2018: A conversation by the sink

I got home and dropped the shopping on the bench and started rifling through the bags. We forgot our canvas ones so we got more plastic ones for 20 cents. I pulled out my toothbrush, “Ah-hah!”

“What?” My boyfriend said.

“I’m going to go brush my teeth. Be a good person. Do my bit for the environment.”

“Alright darl, but I’m not unpacking the shopping by myself.”

“Fine. I’ll be back soon.” And I trotted to the bathroom and wet the brush and put the toothpaste on and started brushing. The bristles began to snap off from the base and disintegrate into my mouth, getting caught between my teeth. Like pubes.

“What the fuck is this?” I said, and I looked at the pack and at the panda wearing sunglasses and realised that the panda wasn’t hot. Or hip. He was smug. He was laughing at me.

He owed me nine dollars.