In three concurrent exhibitions at FELTspace, writer Nix Herriot found a triptych of works, which, despite their differences, shared in their drawing of unlikely connection.

Transcendent connections

As we experienced the emptying of streets and cities, as barricades and borders were thrown up, and as we retreated behind digital screens, it became clear that COVID-19 represented more than just a crisis of epidemiology. As Biao Xiang writes in The Otherness of the Everyday, the pandemic has also precipitated a crisis in regimes of truth.

Social media has assumed newfound importance as a realm of ideological contestation on a global scale. This stems, Biao argues, from the erosion of tangible relations where social truth can be established.

Meng Zhang shares Biao’s anthropological diagnosis of the disappearance of the nearby, the ‘otherness of the everyday’.

Five disembodied limbs rest on earthly plinths. Spatially, the body appears grounded in the material world yet remains isolated within the white space of the gallery.

The artist’s concrete casts echo a tension of the pandemic age: at a time when external forces restrict our capacity for movement, how might we reestablish intimacy with our surroundings? Over Zoom, Meng recounts her experiences of lockdown. Reconnecting with her local butcher and grocers offered a newfound appreciation for everyday human interaction.

Meng’s work actively rediscovers the nearby by directing the viewer’s attention back to the material world. In her garden, she was drawn to the changing shade cast by a tree. “When I sat there and observed the shade and heard the sounds in that backyard place, I felt like this was something I’d ignored. The shade is a canvas.”

Video projections offer glimpses into Meng’s process of observing and recording everyday life. Minutiae — the unintended aeration and imperfections of the casting process, the birdsong and the artist’s spontaneous humming audible in her video recordings — represent tangible reconnections with the everyday world.

Here, the artistic process embodies an evocative nexus between objects and their surroundings.

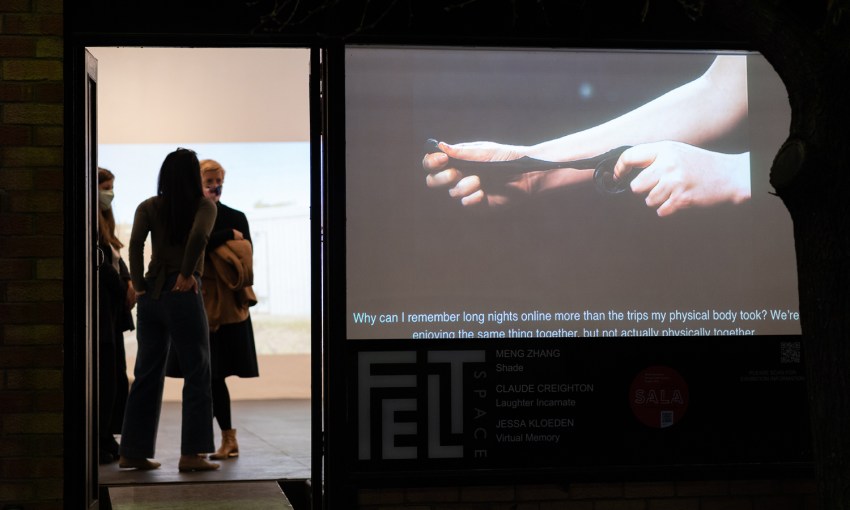

At dusk, I wait outside FELTspace for Virtual Memory to transport me to a very different realm. Like Meng’s practice, Jessa’s work emerged from the creative challenges imposed by the pandemic.

During lockdown, she was compelled to work with video “at a time I had never felt less connected”. Whereas Meng’s artistic impulses are anchored in reconnections with the material world, Jessa articulates a visual poetry from the virtual sphere.

Viewers are guided through nostalgic remnants of technology, towards futuristic and fantastical gamescapes. “I can’t physically take you there,” Jessa explains. But these intangible spaces gesture towards feelings of nostalgia, often for a time many of us were never a part of. Expressed through visual collage, Jessa’s story is united through her narration.

Despite telling a deeply personal story, an affecting universalism emerges: “Even if we aren’t together, we’ll always be connected.” Grappling with meaning in an intangible world, Jessa shares personal thoughts and feelings while suggesting the possibility of shared experiences in the absence of physical togetherness.

In the back gallery, my eye is drawn to the shadows cast by Claude Creighton’s motley suit. Suspended in space, Claude’s appliquéd garment becomes an object of storytelling, animated by the spectre of a fantastical past.

Unlike Meng and Jessa’s works, Laughter Incarnate conjures up the realm of myth. As opaque illustrations of rolling clouds emerge from where the walls meet the ceiling, I imagine who might have once laboured inside such a costume. What kind of world might they have they inhabited?

This body of work has its origins in the artist’s close engagement with medieval history. “I was interested in walking through a threshold space,” Claude explains. Perhaps this explains their interest in the Fool.

Through a comical social position, the Fool was able to transcend the rigid dichotomy between the common people and the court. At a time when the Fool has few obvious homes within modern society, Claude’s imaginative storytelling reminds me of the potentially subversive power of mockery and jest. Inhabiting a time other than the present, Laughter Incarnate remains a costume waiting to be donned.

See the September FELTspace exhibitions here.

FELTspace

12 Compton St

Adelaide 5000 SA

There is no straightforward rubric through which to unite these three works. But, upon reflection, it is hard not to be struck by their universality.

As Jessa explains in Virtual Memory, “this is a story of how we are made human by our connection”. As the pandemic threatens to delimit our horizons, Meng, Jessa and Claude imagine other worlds. We see the artist connected to divergent spheres of meaning—tangible and intangible.

Through visual storytelling, they offer reflections on relationships that have been foregrounded in our plague year. Above all, this exhibition celebrates emergent artists as dynamic and unique narrators of collective experience.

Nix Herriot is an honours candidate in history at the University of Adelaide. He is a researcher of social movements and political radicalism and maintains a close interest in visual culture. He has studied history of art at the University of Adelaide and Edinburgh College of Art.