When Nikki Sullivan started working at the Migration Museum five years ago there were no items catalogued as “queer.” In a new book, the South Australian curator argues museums must give more real estate to LGBTIQ+ stories, and artefacts must be classified in a radical new way.

Queering South Australia’s museums

Although Nikki Sullivan has dedicated a sizeable chunk of her career organising museums – she’s managing the History Trust’s Centre of Democracy – her first impressions of her future workplaces weren’t great.

“I didn’t like it,” she says.

“Firstly, they (museums) didn’t speak to me, and they were not about anything that really interested me.”

They were filled with objects belonging to famous explorers or individuals, Nikki remembers, devoid of links to those living “ordinary” lives such as herself: a Welsh immigrant with kids in tow in the ‘80s, who now identifies as queer.

“It was really only in probably the 1990s, late 1990s, when I really discovered some great social history museums that I was kind of hooked,” Nikki adds.

“What I love about social history museums is that they talk about lives that have been devalued. To me, politically, that’s really important… People who have always been in the margin.”

Late last year Nikki published a book with co-author and former History Trust employee Craig Middleton, titled Queering the Museum, which proposes all museums are heteronormative (a philosophical view that heterosexuality is promoted as the normal or preferred sexual orientation) and need to be disrupted.

Curator Nikki Sullivan

The Migration Museum opened in 1986 and sits under the History Trust of South Australia, like the Centre of Democracy, and values, among other things, the celebration of diversity “in all its many aspects” spanning culture, location, gender, disability and sexuality.

But when Nikki started working with Migration Museum in 2015, she noticed a gap.

“I did a search of our collections database, and I put in the word ‘lesbian’ and didn’t get a single return,” she says. When she typed “gay,” “homosexual,” “queer” or “transgender,” there were also no results.

“Basically, what that said to me was, there is absolutely nothing in the whole of our collection that is related to LGBTQ lives.

“So nothing in our collection, you’re telling me, has ever ever come in contact with these non-normative ways of being? I don’t believe that.

“If so, where does that leave me?”

After five years of work, the museum changed; artefacts that previously didn’t have a queer connection emerged.

For example, the History Trust’s Centre of Democracy currently hangs the South Australian Premier Don Dunstan’s hot pink short shorts, which he wore in 1972 on the steps of Parliament House, as a dazzling display of equality.

They were acquired by the History Trust from Dunstan’s widowed partner, Steven Cheng, and were told to be “an important part of the history of South Australia”.

For some, they represent the progressive changes of the time, such as South Australia’s decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1975 and abortion in 1969, and to others, his identity.

“Don Dunstan’s shorts are there and can tell stories about LGBTIQ lives and legislative change,” says Nikki of the politician, who never came out publicly as bisexual, but had a relationship Steven for over a decade.

“But they wouldn’t have been catalogued that way prior to the work that Craig and I have done as employees.”

The shorts and corresponding Safari suit shirt that stopped the nation

While staff play a large part in how these stories are told, the book also proposes that in order for museums to represent more queer lives, they must shift their processes and assumptions as institutions.

The South Australian Museum’s animal collection, argues Nikki, is an example of this assumption.

“A critique of that Natural History display is that what it says is this: ‘This is family.’”

“When you see, say, lions, you’ll get two lions in there, you’ll get the male lion with the big mane and you get the female lion who doesn’t have one. Sometimes there will be a young lion as well.”

“It just unthinkingly reproduces this idea that there are males, females, they have offspring, that’s what family is.”

One of these Indian porcupines is smaller than the other, but what if it just has a nutrition deficiency?

The South Australian Museum declined to provide a formal statement on how it represents LGBTIQ+ lives, but their website outlines they’re committed to “making Australia’s natural and cultural heritage accessible, engaging and fun.”

A way for museums to represent queer stories with existing collections, Nikki argues, is showcasing multiple interpretations of one item.

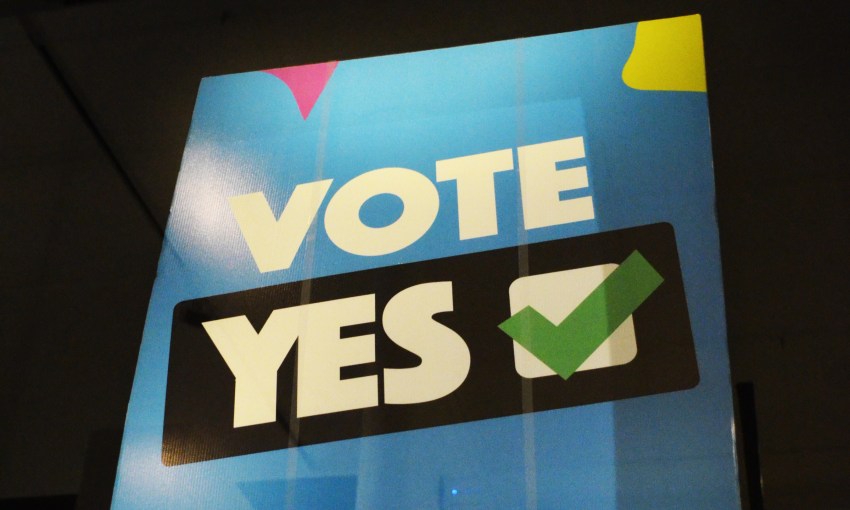

Last year the History Trust launched an online project, also titled Queering the Museum, which asks the public to view 20 digitised objects and offer their interpretations of those things.

So far, items like the Sandman panel van and a Barbie doll camper set have created a tapestry of different memories, outlining notions of gender roles and class.

“What that website’s trying to do is to complicate the process of interpretation and documentation,” Nikki says.

“We want to queer what museums do and say, look, we can do things differently.”