In the first major South Australian presentation of Peter Waples-Crowe’s work, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental presents yet another unapologetically radical suite of work.

Feeling proud with Peter Waples-Crowe

“Oh sorry,” says Peter Waples-Crowe to someone who’s just stepped into the meeting room that he’s sitting in, “do you need this room? No? Okay…” he turns his attention back to the chat after a few seconds, “sorry, where were we?”

He’s on a break at his day-job at Victoria’s Thorne Harbour Health the morning that we chat. He’s caught between two things, our conversation and his work in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health projects at the organisation. This quality, of the friction of being pulled between two places at once is also central to his work as an artist, which will receive its first major South Australian presentation as part of PRIDE at Adelaide Contemporary Experimental (ACE).

PRIDE will be showing from 2 September – 28 October at Adelaide Contemporary Experimental.

Entry is free.

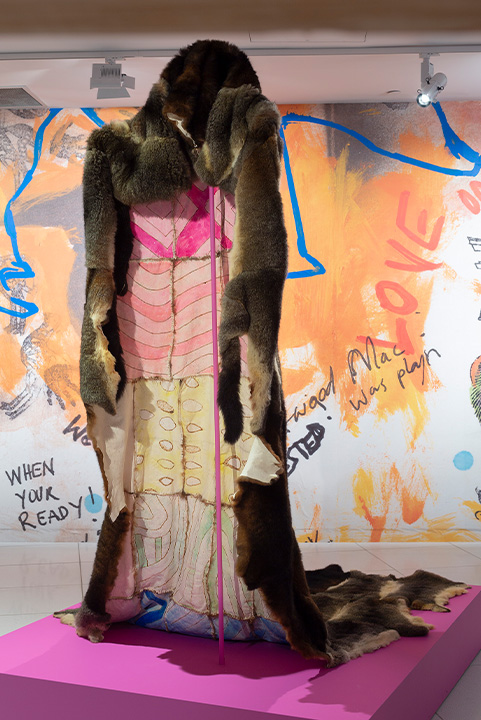

Co-curated by ACE’s Artistic Director Patrice Sharkey and Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri creative Dominic Guerrera, PRIDE will feature works informed by Peter’s work in community organising and activism, providing an insight into the world as battleground for his two identities – queer and Aboriginal, as exemplified by the stunning work of camp Ngarigo Queen – Cloak of queer visibility.

“It’s a big possum skin cloak… it’s beyond that, almost. A standard possum skin cloak is made up of around 38 to 40 pelts. But mine is 50 and it’s got a long train,” he laughs, “There were two different coloured furs, so I put a cross in the back in the fur and then, underneath, I etched or hot-wired the rainbow in cultural designs. I think that piece from 2018 brought together my two worlds. To be cultural and to be queer. To be visible.”

Peter Waples-Crowe, ‘Ngarigo Queen – Cloak of Queer Visibility’ (2018). Picture by Andrew Curtis. Courtesy the artist and the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art.

The work is at once beautiful, moving and exceptionally funny. It’s not a cloak but a cloak, a daring and playful collision of queer and Aboriginal identity that also mourns the loss of queer Aboriginal traditions as a direct result of colonisation.

It is a monument but also, in its apparent functionality as a garment, armour. It is deeply sad, deeply funny and totally defiant in its point of view.

This sense of defiance extends to Peter’s collage work, particularly his short film Ngaya (I am) – a cut-and paste punk take on the Snowy Mountains that will screen as part of the exhibition.

“Ngaya means ‘I am’ in Ngarigo language. I created the work with Rhian Hinkley and composer Harry Covill. The work is an exploration of the mountains and all the issues of the mountains. And also trying to acknowledge that we were living there first, and we are the snow people.”

The work layers colonial paintings, advertisements for the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Scheme to create a funny and sharply insightful portrait of the way non-indigenous people create images of Aboriginal land and people, while destroying both.

In Ngaya, people ski down the slopes of the Australian alps while Ngarigo country burns. Flood waters are something to be frolicked in and the sacred land is something to be conquered, its resources drained for profit. In assembling and dissembling these images and inserting his own paintings, Peter doesn’t plant a stake in the ground of his country because he doesn’t need to, and he doesn’t have to. He removes the stakes that others have planted and plots out a new future for his people and his community.

Peter’s focus on community extends outside of his works and will see him build a community of his own in the gallery, mentoring three emerging Aboriginal creatives from South Australia to showcase works of their own as part of the exhibition.

“The young people are really proud of their identities, but sometimes lack connection to culture and in spirituality. So, hopefully my work sort of does that,” Peter says.

“Working with three other artists from Adelaide has been great. They’re all riffing on the work and giving their own interpretation on the word pride, as well… It’s really exciting.”