As climate catastrophe draws closer and action to avert disaster remains stalled, there is no option but to protest as if humanity's survival hangs in the balance, writes Extinction Rebellion SA spokesperson Ben Brooker.

Protest like the world is ending (because it is)

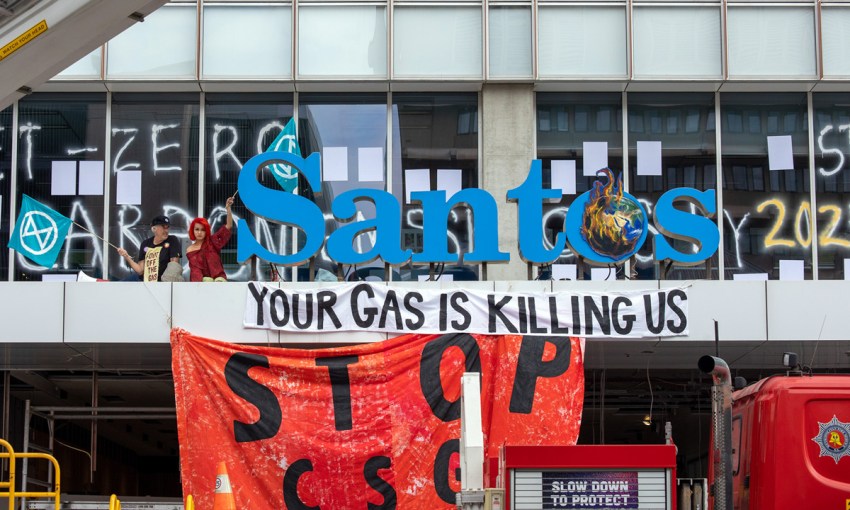

Last Wednesday, six members of Extinction Rebellion SA glued themselves to Flinders Street and scaled the awning of Santos’ headquarters.

They were protesting the company’s ongoing investments in fossil fuels, like the controversial Narrabri coal seam gas project in north-west New South Wales.

Ben Brooker is an Adelaide-based writer and a spokesperson for Extinction Rebellion SA.

All were arrested and charged with various offences, including loitering, disturbing the peace, and trespass. They’ve since been released, although not, in some cases, without onerous bail conditions, which are currently being challenged.

A few days before the action, I sat down with News Corp’s David Penberthy for an interview sparked by an Extinction Rebellion protest at the office of retiring Liberal MP Nicolle Flint.

He was surprised I agreed and frankly I was surprised he asked. I reminded Penberthy of Extinction Rebellion’s past targeting of News Corp, but I needn’t have done.

Over coffee in a Hindley Street cafe he was quick to defend his climate credentials. He believes in climate change, he told me. He isn’t Andrew Bolt. There are plenty of people at News Corp who don’t share the shock jock’s denialist views.

Yet, a couple of days after the Santos action made national headlines, Penberthy opined in The Advertiser that “By designing a protest that is set about to cause inconvenience, these people risk losing the argument.”

As a spokesperson for Extinction Rebellion SA, I’ve heard many variations on this theme since Wednesday’s arrests, including on ABC Radio Adelaide. They’re nothing new. Nor are Extinction Rebellion’s tactics of nonviolent civil disobedience, which are part of a long lineage of peaceful protest stretching back to Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

As one of the movement’s founders, Roger Hallam, has written, “We are simply rediscovering what people do when they have had enough of failure and really want to make a difference.”

The logic whereby protest is tolerated but civil disobedience is rejected is one that will be familiar to activists of all stripes, including those behind Black Lives Matter.

While paying lip service to the right of citizens to protest, critics of movements such as Extinction Rebellion and BLM prefer it when they can safely ignore our demands.

The reality is that the polite rallies and campaigning we have undertaken for years no longer work. They don’t sway governments, and they don’t attract media.

The irony, of course, is that the very fact that so much has been written and said about Extinction Rebellion since Wednesday proves that the tactics our critics decry are working. They weren’t paying attention before. They are now.

Today few people would argue that the disruptive but nonviolent tactics of the civil rights movement – boycotts, freedom rides, voter registration drives, sit-ins, and marches, all often resulting in mass arrests – were unsuccessful. But while critics of movements such as Extinction Rebellion venerate a whitewashed version of Martin Luther King’s legacy, they simultaneously forget or ignore the antipathy with which his actions were widely met at the time.

As writer and activist Francesca Willow has written: “Just like climate protestors being arrested, Black Lives Matter blocking roads, or business owners refusing service to Trump officials, nonviolent direct action is rarely popular or orderly. But it is on the right side of history, and of morality.”

In a sense, climate and anti-racism protests don’t cause disruption so much as reveal it. Climate change is already plunging the world into chaos – whether in our ecosystems, food chains, or geopolitics – just as racism exerts massive disruption in the lives of people of colour whether white people are aware of the fact or not.

There are barely any climate deniers anymore. Yet our parliament remains stacked with people, many of them in the most senior positions of power, who may as well be.

Scott Morrison doesn’t reject the reality of anthropogenic climate change. But nor does he act as though he understands how grave a threat it poses to everyone, including his children and grandchildren. He won’t even commit to the hopelessly inadequate global standard of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Morrison’s former finance minister, Mathias Cormann, is now, ludicrously, the chief of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). And people wonder why, when our parliamentarians face as little accountability for stymying climate action as they do for sweeping allegations of sexual harassment and assault under the carpet, we’ve reached the limits of our patience.

I often think that in the not too distant future we will look back on this moment in history in disbelief and shame.

We will hang our heads to think that while the planet burned and our leaders did nothing, a handful of students, grandmothers, and other ‘ordinary’ people risked their freedom to speak up as large parts of society denounced them. Like nitpicking children, we accused climate activists of hypocrisy for driving cars and using plastic bags, as the Great Barrier Reef died and the great ice sheets of Greenland and the Antarctic leaked away to nothing.

It cannot be stated often or strongly enough how dire the situation is.

According to a recent report by the Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration, the climate is warming more and faster than predicted by organisations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Globally we’re on track for a disastrous 3°C–5°C of warming by 2100.

According to evidence recently given before the Senate by the Bureau of Meteorology, Australia (which is consistently ranked among the worst performing countries when it comes to climate action) is headed for 4.4°C of warming by the end of the century.

Needless to say, this would be a catastrophe on par with the nation going to war. So why are we not preparing for it as though, like with a war, our entire way of life hangs in the balance?

Perhaps you think you’ve heard all this before or that you need no further convincing of the Cormac McCarthy-like scenario we face. The trouble, as CleanChoice CEO Tom Matzzie recently tweeted, is that ‘the divide between those of us who understand the scale of response needed for climate change and even those who are our allies is too wide.’

Not everybody can or should expose themselves to the risk of arrest. But for those of us who, like me, have no good reason not to given what’s at stake, the risk of failing to do so may be far greater.

I’ve seen the unwillingness or inability to match climate action with rhetoric many times. At a recent Extinction Rebellion traffic swarm in Hahndorf, an enraged motorist got out of his car, declared that he supported climate action, then proceeded to yell at us to get out of his way.

The more I think about it, the more it seems to me that whether or not we save the planet will come down to how much we can narrow the gap between what we believe and what we do in light of our beliefs.

Perhaps you think that a handful of people gluing themselves to a road or holding up traffic for a few minutes won’t change anything. But, like King Lear in one of his more lucid moments, I know this to be true: that nothing will come of nothing.

It’s only through action, even when the outcomes are in doubt, that anything can change. We could not have guessed, for example, that a small, non-disruptive protest outside Nicolle Flint’s office would have as much impact as it did.

Sometimes I think of it this way: If the climate crisis didn’t exist but a terrorist group with a new super weapon that caused the same effects was threatening the world, would any doubt at all remain as to how quickly and seriously we should respond?

I don’t know a single member of Extinction Rebellion who wants to do what they do, who doesn’t fret every day about the organisation’s tactics. But this super weapon is real, it is loaded, and it is pointed at all our heads.

It’s a sign of what Amitav Ghosh has called ‘the great derangement’ that, at present, climate activists face the threat of fines, jail, and punitive bail conditions for calling attention to this weapon while those who, like Mathias Cormann, do nothing to prevent its use when they have the power to do so, are elevated to top diplomatic roles.

To call for Extinction Rebellion to tone down its methods is to fundamentally misunderstand the nature of power and protest.

There may be nothing polite about blocking traffic and graffitiing buildings, but ask yourself this, as Martin Luther King once did: are you more concerned about tranquility and the status quo or justice and humanity?