Ahead of the City of Adelaide naming a laneway in honour of South Australian reggae band No Fixed Address, CityMag spoke with guitarist Ricky Harrison about coming up as an Indigenous artist in Adelaide's 1980s music scene.

No Fixed Address given permanent CBD address

Ricky Harrison of No Fixed Address says he was “blown away” when he found out the City of Adelaide would name a laneway after the band he played guitar in for over a decade.

He did, however, find it slightly ironic.

A mural and the city street name dedicated to No Fixed Address will be unveiled in the band’s honour this year.

Connect No Fixed Address:

Facebook

“We used to get a lot of jokes like that, about our name,” Ricky says, laughing.

“We were all from different places and living in the city of Adelaide, but we were forever moving around.

“But it wasn’t really by choice, we were young fellas back then. We didn’t have a permanent address that we were staying at.”

The City of Adelaide recently announced No Fixed Address would be the fifth band to be given a street name in the city – following Cold Chisel, The Angels, Paul Kelly and Sia – with Lindes Lane set to become No Fixed Address Lane.

Adelaide Lord Mayor Sandy Verschoor said in a statement she was “proud that we can honour No Fixed Address through this project” celebrating Adelaide’s musical roots.

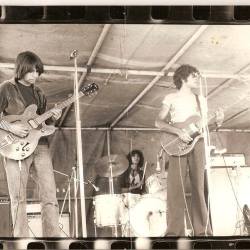

No Fixed Address formed in 1979 and were “the band that kicked everything off”, Ricky says.

“We were fighting both sides for our music, for our future and for the future of Aboriginal music in Australia. We were fighting everybody for it.”

The five-piece formed only four years after the Racial Discrimination Act passed Federal Parliament – making it illegal to discriminate against someone based on their race or descent – and less than two decades since the repeal of the 1911 ‘Aborigines Act‘, which enshrined in law the protection of free movement for Aboriginal Australian residents in South Australia.

No Fixed Address threw some much-needed colour into a predominantly white mainstream music scene, dominated by rock bands like INXS, Midnight Oil and Men at Work. They blended reggae and rock to create politically charged music.

Songs like ‘Pigs’ and ‘40,000 years’ captured their experiences as young Black men living in a “white man’s world” – a repeated refrain from their song ‘We Have Survived’ – while ‘The Vision’ fused Indigenous and Western instruments to create a new sound.

“But back then we never really thought of it as political,” Ricky says, “we were just young Aboriginal men.

“We were empowering a lot of other Aboriginal people through our words, and again performing and writing about the plight of how we saw things.”

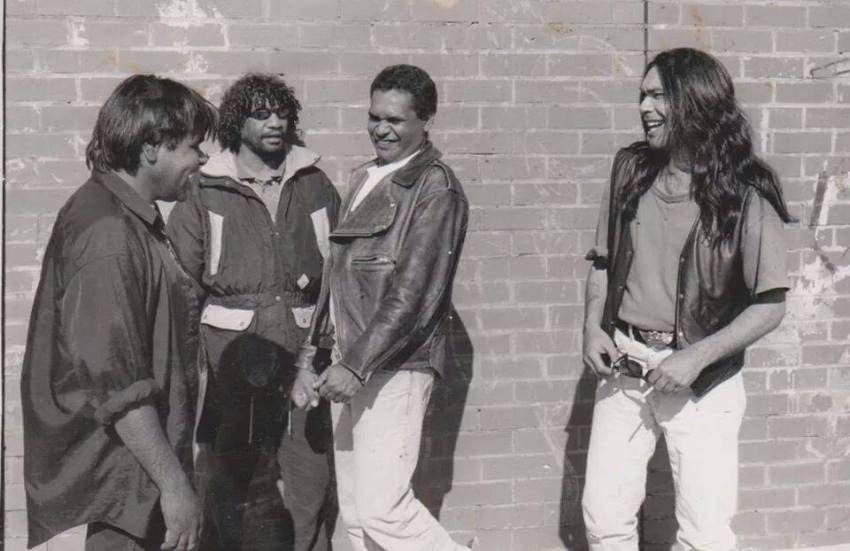

Bart Willoughby (middle, bottom row) says he’s proud and overwhelmed a lane would be named after the band. “No Fixed Address led the way into the rock ‘n’ roll field of Australia for young up-and-coming Aboriginal bands.”

No Fixed Address were the first Aboriginal Australian band to tour overseas, and in 2011 the original members were inducted into the National Indigenous Music Awards Hall of Fame.

Drummer and vocalist Bart Willoughby, guitarist Leslie Lovegrove Freeman, bassist John Miller, guitarist Ricky, and saxophonist Veronica Rankine all met while studying at the University of Adelaide’s Centre for Aboriginal Studies in Music (CASM) in the city.

CASM is the only university-based centre devoted to Australian Indigenous music, and boasts alumni such as Zaachariaha Fielding of electro-pop duo Electric Fields, as well as leaders in education, health and government.

“You’ve got David Ross who’s the head of the Central Land Council and the other guys I went to university with turned out really good,” Ricky says.

“I hitchhiked from Morwell in Victoria with my cousin Tony to CASM. It was one of these beacon lights. It attracted everybody there.”

CASM director Professor Aaron Corn said in a statement it was “wonderful” to see No Fixed Address acknowledged by the City of Adelaide because they greatly contributed to Australia’s music and cultural history.

Ricky says the band leant into reggae because they saw musicians in Jamaica using it as a vehicle to call out government oppression, and could use it in a similar way.

Being a young Black man in ‘80s Australia was fun, Ricky says, but there was “always that thing of looking over your shoulders for cops and people being racist.”

“There wasn’t a lot of racism going around that I came across, but when it did it was like this big rock falls on you.”

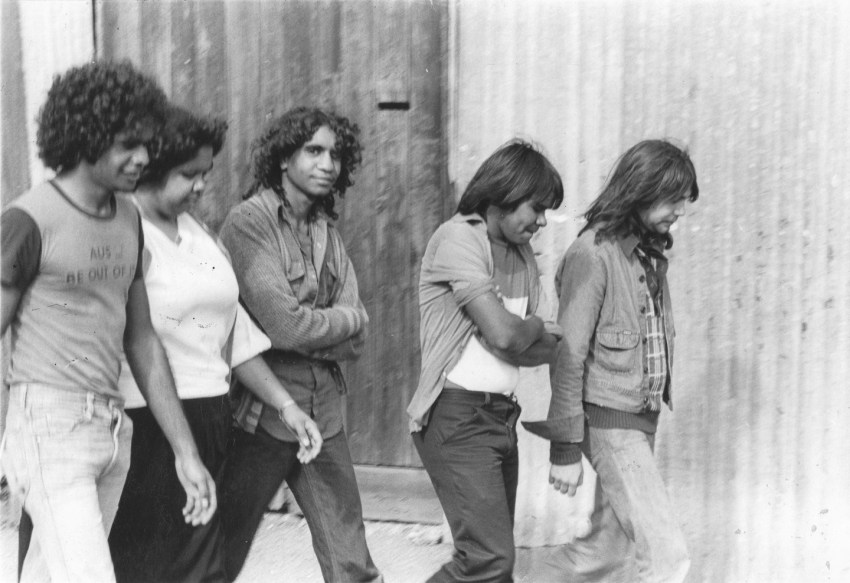

The band also featured in the award-winning cult film Wrong Side of the Road by Ned Lander, which told a fictionalised story of No Fixed Address and Us Mob, another Aboriginal Australian band from CASM, navigating racist police and discriminatory attitudes in South Australia.

The film received international attention and fostered greater awareness among national audiences of how First Nations people were treated.

Ricky says part of the band’s job was to bring this to light for white audiences, but also bring Indigenous communities together.

“For me, it wasn’t really about racism, it was more about community and the disunity within the community at the time,” he explains.

Australia has a long way to go in terms of recognising First Nations people and providing equity, Ricky says, but this means the message and the music of No Fixed Address is still relevant.

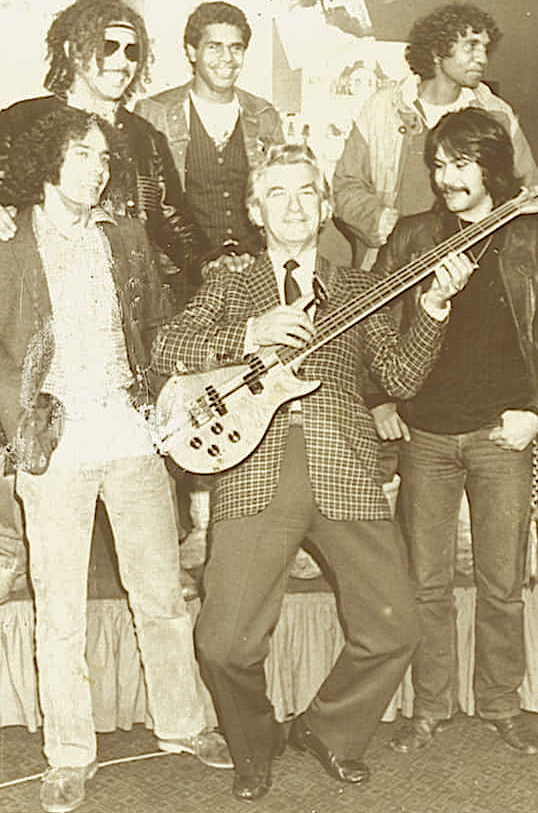

No Fixed Address had many rotating members, but Bart Willoughby (third from left) remained a constant. (Right) The band with PM Bob Hawke

The band’s 1982 album From My Eyes, which was launched at the Hilton Hotel by former Prime Minister Bob Hawke, contains many contemporary calls to action, such as decolonisation and Indigenous Australians being given real assets for prosperity, such as land, Ricky says.

“The thing with Aboriginal people [is] not having access to that wealth creation and all that, which is why today, a lot of them [are] living the way they are because they were never given the opportunity,” he says.

“But back then a lot of people still living on missions, and needed a ticket to get off there.

“We were the first generation that came away from the mentality of there only being one Aboriginal family per town or one or two or three per town. We were really the first generation at CASM, and this is one thing a lot of people didn’t understand.”

Ricky will travel to Adelaide from his property in Morwell, Victoria, when the City of Adelaide unveils a mural of the band to accompany the street naming later this year.