Misgendered and misnamed

Words: Angela Skujins

Portrait photography: Morgan Sette

Additional imagery: Sam Balye

Three gender-diverse students tell CityMag being misnamed and misgendered while studying has led to anxiety, depression, dropped courses, and an erosion of trust in the state’s higher education system.

“We’re not at university to have trans-rights battles,” says University of Adelaide student, Ollie Patterson. “We’re at university to learn about whatever we’re meant to be learning about.

“Being deadnamed and misgendered makes it really difficult to go to university. It also made it unsettling to be there after-hours, because if you’re not respected in your conversation, it’s hard to believe that you’ll be respected in your autonomy.”

For a lot of people, starting tertiary education is an opportunity to unveil a new identity. Shed the old baggage, make new friends. Ultimately, you can be whoever you want to be.

But for some trans, non-binary and gender-diverse students, this new educational environment is a political battleground where their identity is questioned, by tutors and the academic system.

For Ollie, being ‘outed’ or ‘deadnamed’ – another term for being misgendered or misnamed – makes them feel “unseen and insignificant”, and has had educational and emotional consequences.

“In the classes where I couldn’t be myself, I would just not know how to talk to people, not know how to learn, not be able to concentrate because I was so hyper-aware of being perceived. It’s just a lot,” they say.

Kelly Vincent, policy and project officer for the LGBTIQA+ advocacy group South Australian Rainbow Advocacy Alliance, says it’s important trans, gender-diverse and non-binary young people are supported with simple acts like naming and gendering, as the self-harm and suicide rate is “unacceptably high” among the group.

A recent University of Melbourne paper found just under half – 43 per cent – of trans respondents reported having attempted suicide, with lifetime depression reported in 73 per cent.

“We get contacted by people who were misgendered at school, university, even following them into adulthood [and] in the workplace,” Kelly says.

“It has had a devastating impact.

“People know who they are inside and out – and to constantly have that ignored and put down because people assume they know better than you, when you’ve lived in your body and your mind your entire life, is incredibly demeaning, especially when you’ve taken a long time to find that out.”

OLLIE PATTERSON

Long-limbed, green-eyed and articulate, Ollie Patterson exudes confidence and pride in their identity. They explain this didn’t happen overnight.

Ollie started their public transition in the second semester of 2017, when they were a student at the University of Adelaide. While on an exchange program in the US that same year, Ollie saw how far educational institutions had progressed in their treatment of trans students. In their first classes overseas, Ollie introduced themself by their new name, with they/them pronouns.

Ollie returned to Adelaide at the beginning of 2018, and they “tried to bring back everything that I had learned from the States”.

They sent emails to their new University of Adelaide’s lecturers and tutors explaining how they want to be referred to in class, and knowing there could be other trans or gender-diverse students in these settings, Ollie suggested educators begin their first lesson by letting pupils tell the room which names and pronouns they want to use. That, or a name-tag system.

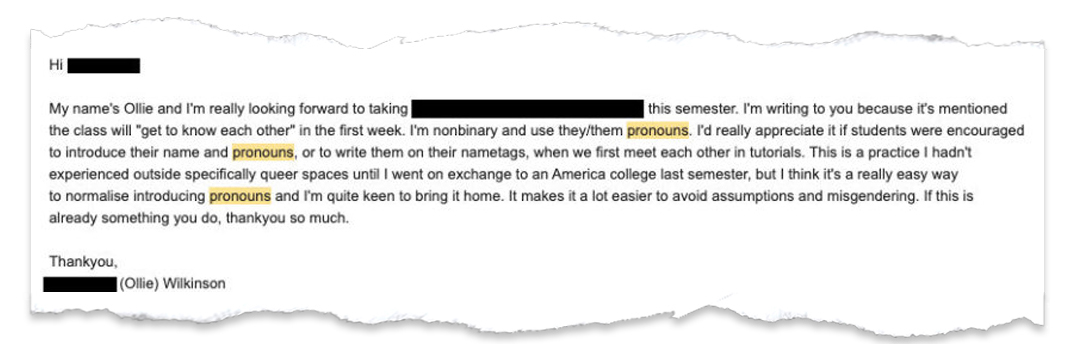

An email Ollie sent to a tutor explaining their name and pronoun preferences.

“I think it’s a really easy way to normalise introducing pronouns, and I’m quite keen to bring it home,” Ollie said in an email to their teachers in February 2018. “It makes it a lot easier to avoid assumptions and misgendering.”

Only half of the tutors were supportive of Ollie’s suggestion. The uncooperative responses they received lingered.

“I had [one] teacher who was like, ‘I just don’t want to stir up trouble; I don’t want to make it weird in the first tutorial,’” Ollie says. “That made it weird for me and fine for everyone else.”

Later that year, a tutor – who CityMag has chosen not to name – misgendered Ollie in front of the class and revealed Ollie was experiencing mental health issues. This had a detrimental impact on Ollie’s mental health.

“[The tutor] told the whole class that ‘[Birthname] has all these issues and will be taking extra time… If any of you need some extra time, just let me know’,” Ollie says.

“He was trying to be kind, I think, but it was so inappropriate and completely shook me right before an exam.

“The next time [the tutor] deadnamed me in class, I walked out and went straight to the counselling centre [and] told them, ‘This course is ruining my mental health, and they were like, ‘Why don’t you stop studying?’

“I said, ‘Okay – I’m done.’ I didn’t feel like I could keep going. I didn’t feel I could do it anymore.”

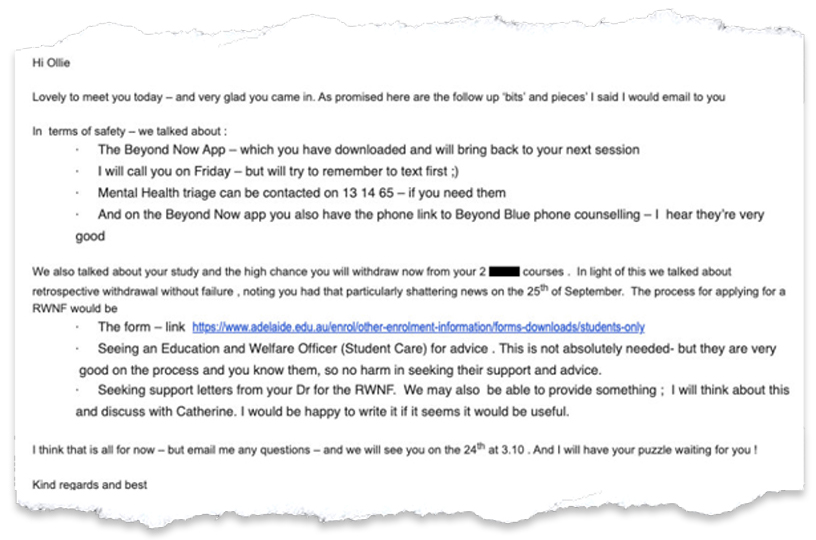

An email from a University of Adelaide counsellor to Ollie confirming they considered dropping a class.

An email from a University of Adelaide counsellor to Ollie, dated 16 October 2018, says during the session they spoke about the “high chance” Ollie would withdraw from two courses.

“We talked about retrospective withdrawal without failure,” the email says. The counsellor also included information regarding mental health safety services.

Prior to visiting the counsellor, Ollie organised a meeting with the University to speak about what had happened. CityMag has seen an email regarding the appointment, but Ollie felt this catch up went nowhere.

University of Adelaide Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Professor Jennie Shaw, told CityMag she couldn’t comment on the experiences of individual students due to privacy provisions, but the university was committed to providing a “safe, respectful and supportive environment for its community, especially marginalised groups”.

“The University of Adelaide has produced Inclusive Language Guidelines (Oct 2018) which are available on both the Safer Campus Community website and HR website and discuss gender/pronouns and gender identity,” the Deputy Vice-Chancellor says via email.

“More broadly, our Equal Opportunity Policy encourages an inclusive, respectful and fair environment for all people. New staff are required to complete Equal Opportunity Training within their first three months of employment. An LGBTIQ inclusion module is available on the Safer Campus Community website and discusses inclusion and mindful language in the workplace.

“All University Counsellors, International Student Advisors and Disability Advisors are ALLY trained. Students are able to nominate a preferred name on their university email and MyUni but presently may still need to communicate their preferred name to academic or professional staff.

“The University is committed to taking action if staff are not upholding these values.”

Ollie says they’ve never witnessed a tutor or professor face disciplinary action due to misgendering or misnaming a trans, non-binary or gender-diverse student. Instead, students like Ollie have been told “‘We’ll do better next time,’” they say.

“The responsibility to make everyone comfortable is shifted to trans students. There is an exhausting expectation that we should understand and passively accept that our existence is mind-boggling to some staff.”

EIRA THORSTENSSON

Eira Thorstensson wears a black blouse with large, printed orange flowers splashed across the front. The bubbly first-year TAFE SA student is currently studying horticulture. They love being outside, revegetating and helping things grow.

Eira has faced their own hurdles as a trans student within TAFE. Like Ollie, they speak to every tutor and lecturer prior to the semester commencing to communicate their name and pronoun preferences, but Eira prefers to do this face-to-face.

“They can’t make any mistakes when I’m here in person,” Eira says, tucking a strand of shoulder-length hair behind their ear.

“There can be a bit of anxiety showing up the first day and having to desperately try to track down the lecturer before they read the roll.

“Being like, ‘Hello, that’s me, but also not that name’ in front of a whole class of people, it can be stressful.’”

Eira’s first foray into the world of tertiary education started in January 2018, studying a dual course at Flinders University and TAFE SA.

In 2017, they started taking hormones, and two years later in 2019 started going by the name Eira. It was roughly six months after this, in 2020, they tried to change the details lodged in TAFE’s administrative system to reflect their new name, but this wasn’t successful.

In trying to register ‘Eira’ as their preferred name, they discovered the system would only allow a preferred name if there had been a legal name change. Eira has Swedish citizenship, complicating the process of changing their name. To this day their name has not been legally changed.

Eira continued their course under their birthname. Although they found many of their lecturers “affirming” and “respectful”, they never felt comfortable coming out publicly within this environment.

“As a naturally private person I never felt confident in bringing up that I wanted to use a different name when everyone already knew me by my birthname,” they say.

“If I could have changed it on the system I would have powered through, but the idea of having to correct every new lecturer on top of everyone who already knew my birthname felt incredibly daunting.”

Eira Thorstensson

Eventually, they dropped out of the course and switched to horticulture. They say this was because they wanted to study something different, as well as for the opportunity for “a clean slate; new name, new cohort.”

To this day Eira has still not successfully accessed the ‘preferred name’ option within the TAFE system, which has led to some “uncomfortable experiences”. Earlier this year, they unknowingly enrolled in an online-only unit they could not withdraw from. Because Eira had not changed their name in the TAFE system, their profile on the website was registered under their birthname.

“I’m sitting there being ‘Shit, shit, shit, oh my god, they’re going to work shit out and people are going to get really weird’,” Eira says.

“I know that 90 per cent of the other people in this very small class are other people I’ve had in other classes who know me as Eira.”

Not wanting to be associated on-screen with their birthname, Eira turned off the camera and only contributed to conversation through the chat function.

After the tutorial, another student asked Eira where they were as they didn’t see them present on the student list.

“I said, without thinking, I was there,” Eira says. “I could tell he cottoned on too, and went ‘Ohh’. That was a bit of an uncomfortable experience of being like, ‘Okay, so you just worked out everything that’s going on here’.

“This whole thing is about being able to control how you tell people. I’m pretty open about what my deadname is. It’s not something that bothers me much, but I’d like to be able to control when and how that happens.”

TAFE SA Chief Executive David Coltman told CityMag in a statement he is “concerned” about Eira’s experience, and where issues are raised, student support services are available to “rectify concerns and advocate” on behalf of students.

“A feedback and complaints process is available to all TAFE SA students through our website. TAFE SA is constantly seeking to improve our students’ experience across all areas of their education and training at TAFE SA,” he says via email.

He adds TAFE SA introduced the ‘preferred name’ option for student record systems in 2019. This was established “in response” to “guidance” received from the gender-diverse student community.

Eira says despite the preferred name option being “apparently available”, they’re “frustrated” they weren’t able to access it.

Ultimately, Eira is at TAFE to learn, but they also reveal feeling a “constant” internal debate about whether to advocate for the trans community or simply be a student.

“When I was younger, I very much went, ‘No, I have to stand up for myself. Queer rights’,” Eira says. “Now I’ve got to a point where I’m one person in my own life, I just actually have to survive and live and learn.

“I’m just meant to be I’m here to educate myself. I’m not here to make people suddenly understand gender.”

ELI MATTHEW

Despite being misgendered and misnamed on numerous occasions while studying at the University of Adelaide in 2015 and 2016, Elijah Matthew maintains a sunny disposition.

“I mean, I graduated. I’ve got three degrees now,” he laughs.

As Elijah – who goes by Eli – chuckles, the curls in his mullet bounce. It seems not a single hair on his head has ever been anything but joyfully buoyant.

At the end of 2013, Eli told his friends and family he wanted to be referred to as ‘Eli’, using he/them pronouns. Prior to this, at the beginning of 2013, he enrolled to study at the University of Adelaide under his birthname, but deferred.

When Eli came back to study in 2015, his academic record still used his birthname. “I hadn’t been able to change my name yet,” Eli explains.

“For the whole second semester of 2015, I had to use my email address… and the University of Adelaide wouldn’t let me have a preferred name.

“When I talked to the University of Adelaide about it, they said that they couldn’t [implement a preferred name] unless you officially changed your legal name.”

Like most trans and non-binary students, he would email lecturers prior to courses commencing to explain his preferred name and pronouns.

During one of these email communications with a tutor in 2015, Eli was called his deadname, despite signing the email off with his new name.

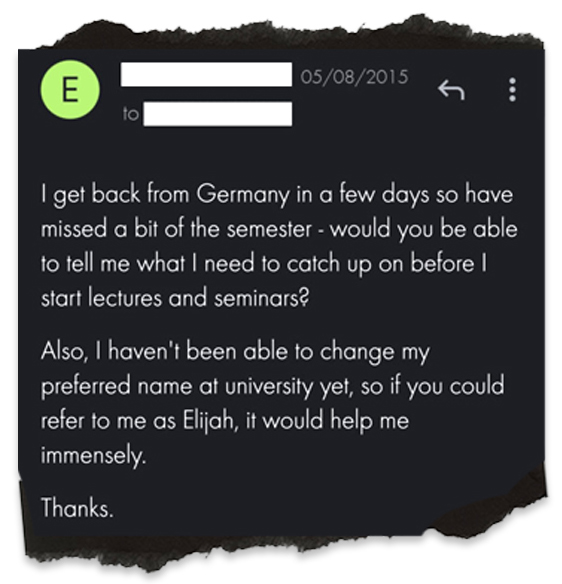

“I haven’t been able to change my preferred name at university yet, so if you could refer to me as Elijah it would help me immensely,” the email to the tutor, dated 5 August 2015, says.

An email from Eli asking a tutor refer to him as Elijah.

The reply did not acknowledge this statement, and referred to Eli by his birthname in the first line.

A few months earlier, in the second semester of 2015, Eli stopped attending a class after the lecturer refused to refer to him with male pronouns and his preferred name.

“I stopped going to the class, and I failed, because he refused to do it,” Eli explains.

“I would send him emails, as he would call me the name on the email system, but that led to me not attending class because he never gendered me correctly… despite the numerous amounts of times I pointed it out to him.

“My GPA got pulled down significantly because of that.”

At the beginning of 2016, Eli transferred into a Bachelor of Laws at the University of Adelaide, and later that year successfully changed his legal name. ‘Elijah’ was finally cemented in the university’s system. A lot of the misnaming and misgendering then went away.

Later that year, Eli was invited to a round table at the university as a recipient of the Dr Duncan Memorial Scholarship – a grant awarded to University of Adelaide students with a financial need and a “demonstrated commitment” to LGBTIQA+ issues. He spoke about his experience trying to register his preferred name with the university, but no change was made.

“They were completely appalled by it, but there’s not much they, as a separate faculty, can do about it,” Eli says.

CityMag asked Professor Shaw, the University of Adelaide Deputy Vice-Chancellor, what action was taken by the university after the misgendering and misnaming was raised with the law faculty in 2016, but she did not respond directly.

She reiterated the university was unable to comment on the experiences of individual students due to privacy provisions.

Eli considers himself “fortunate” to have changed his name relatively quickly and to have only endured a short period of misgendering and misnaming. But he knows of others are not so lucky.

“I’ve heard from other people that it hasn’t really improved that much,” he says.

A WAY FORWARD

According to a 2021 La Trobe study of Australian LGBTQ+ people aged 14–21, 28 per cent of respondents said they couldn’t safely use their chosen name or pronouns in educational settings.

A report produced from the study, titled Writing Themselves In 4, showed 46.9 per cent of respondents “sometimes” and “frequently” hear negative remarks about gender identity or expression in these settings.

And almost one sixth – 15.2 per cent – said they had missed at least one school day due to feeling unsafe or uncomfortable, with 34.3 per cent of respondents finding their teachers “not supportive” in regards to sexuality or gender identity.

An earlier study from 2018 found transgender youth who were supported in using their chosen names in spaces like schools were 29 per cent less likely to experience suicidal ideation, and 56 per cent less likely to attempt suicide.

The data show using the right words goes a long way.

Kelly Vincent says the South Australian Rainbow Advocacy Alliance is calling for a “whole of government approach” regarding diversity inclusion, including naming and gendering, among youth.

She says the training and policies can vary “a lot” between schools, government departments and agencies, and the process should be streamlined to ensure there are no discrepancies.

“It’s really important that we get this consistent so that your human rights don’t vary depending on which agency you’re visiting or which school you happen to attend,” Kelly says.

The Writing Themselves In 4 report recommends shaping educational settings to ensure the existence and promotion of LGBTQA+ anti-bullying policies. It also recommends including “supporting affirmation and facilitating a sense of safety at school, TAFE or university.”

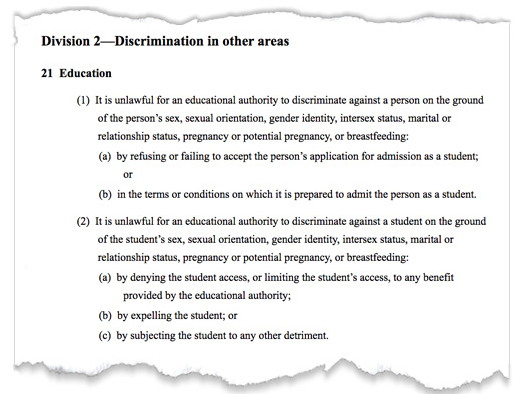

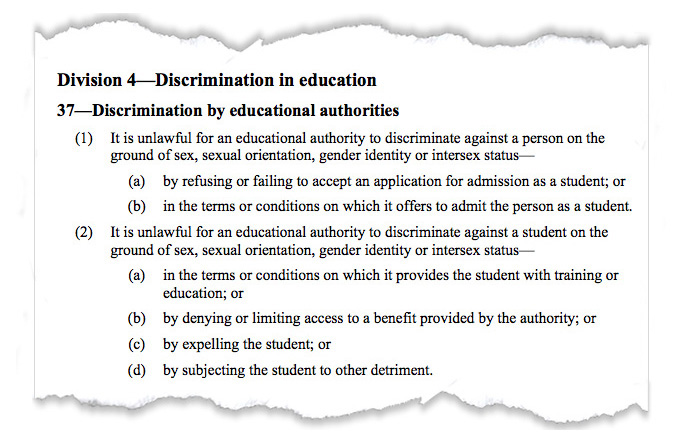

A portion of the Sex Discrimination Act (1984).

Laws protecting trans people from discrimination in educational settings already exist at both the state and federal level, the Equal Opportunity Act and Sex Discrimination Act respectively.

The Australian Human Rights Commission could not provide CityMag the number of misgendering or misnaming complaints they received in the last year, but said “this is a matter that could potentially form the basis of a complaint to a commission”.

South Australia’s Equal Opportunity Commissioner, Jodeen Carney, also could not disclose how many misgendering or misnaming complaints were lodged against specific organisations or individuals in tertiary education settings in the state.

However, she said there were “protections” in the law which “would include” instances where an individual is being discriminated against, “including, for example, where they are subjected to a detriment or being offered different terms or conditions for their education”.

A portion of the South Australian Equal Opportunity Act (1984).

Eli says there is still a clear “power imbalance” between trans and cisgender people in the classroom. As the majority population in most settings, he wants to see cisgender students stand up when they see situations go awry.

“You’re like, ‘If I stand up, will anyone stand up for me? If I make a point about this, will people tell me to shut up and stop being so sensitive?’” Eli says.

“But that’s what allies should also do. It’s tiring having to do all of it by ourselves all the time.”

Eira believes more cultural awareness training would help, and not just at the executive level. Students “are interacting with the lecturers every single day,” they say, and they’re the ones who need it.

Nominating preferred pronouns within the administrative system could also be beneficial to some students,” Eira says. “I think it is really valuable for the people who absolutely want to be able to have that as an option.”

Ollie wants all University of Adelaide staff to undertake the ALLY training, and for the institution to follow through on its commitment with disciplinary action.

“The people who aren’t going to respect it, aren’t going choose to do that unless they’re told they actually have to,” Ollie says.

“If it’s not seen as a necessity, to do the inclusive training, then it’s not seen as a necessity to be inclusive.”

If this story raised issues for you, call LifeLine on 13 11 14. Alternative non-crisis out-of-hours support services include QLife – a counselling and referral service for people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and intersex – from 3pm to midnight on 1800 184 527. The Kids Helpline (up to 25 years) phone service is available every hour of the week on 1800 551 800.