State Library Director Geoff Strempel says the way the institution has dealt with Indigenous material over its 187-year history has "not been good", but it has plans to repair its relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

How the State Library failed First Nations people

Geoff Strempel has been director at the State Library of South Australia for three and a half years.

For over a century, the institution has housed some of the state’s most treasured art and cultural materials.

Founded in 1834 by an “enthusiastic group of prospective colonists” (in its own words), the grandiose library aims to cultivate and spread knowledge through its hundreds of photographs, books, art pieces, audiovisual and electronic material, and oral histories collected from across Australia and abroad.

We’re told the underground basement alone contains over 60km of Adelaide’s written history.

Despite the impressive collection, Geoff admits when it comes to the institution’s relationship and engagement with First Nations people, “we have not been good.”

“We’re about to publish the strategic plan, which says as a library we have not been good around properly and culturally sensitively managing Indigenous collections or engagement of Indigenous people,” he explains.

“My board has just signed off on a statement saying this is where we’re headed, and part of that is employing Aboriginal people to work with the collections and their community to help us to get better at it.”

The State Library has 135 full-time-equivalent staff, only two of whom identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

That’s 1.48 per cent – which is less than the percentage of Aboriginal employees the South Australian public sector achieved overall last year (2.13 per cent).

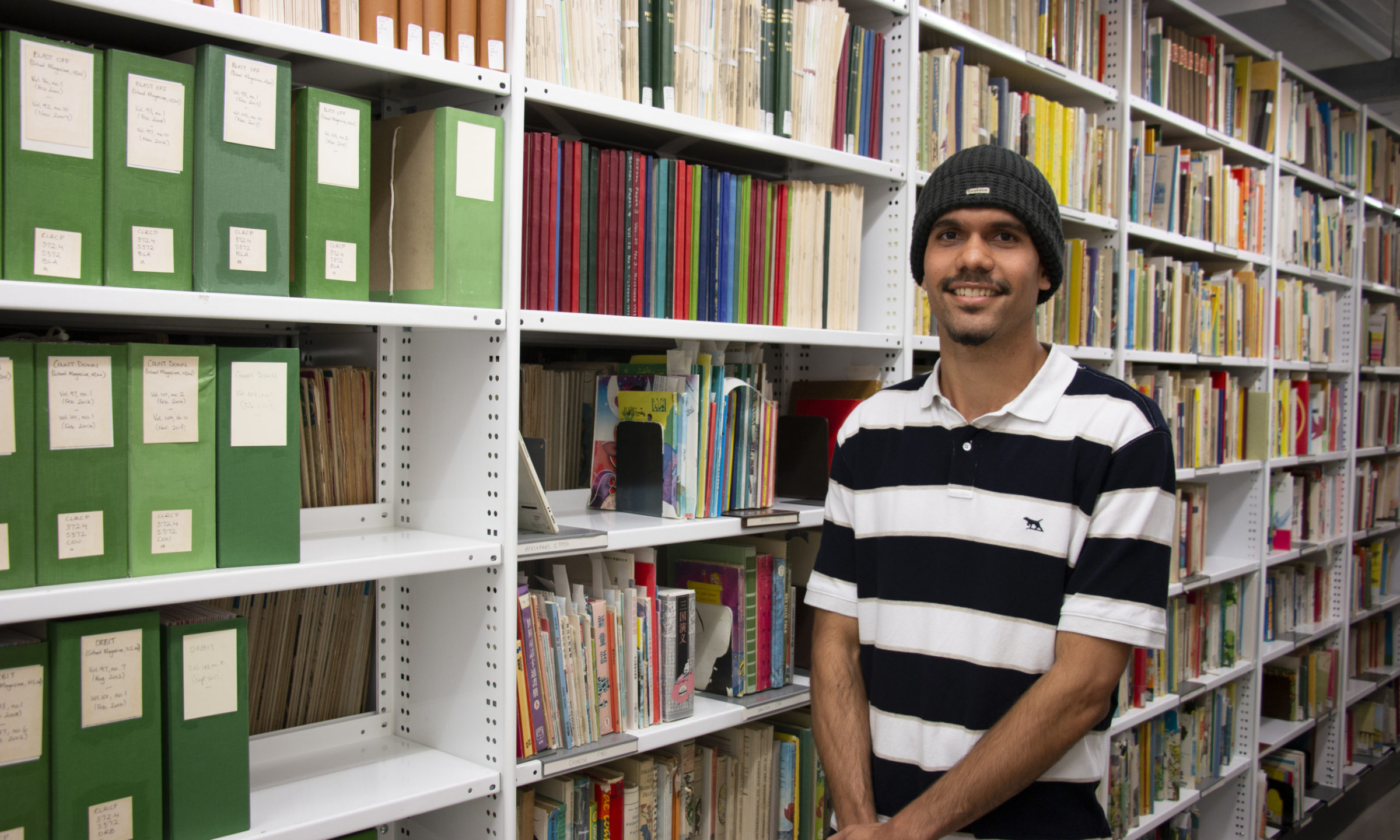

Jamie Hampton in the bowels of the State Library of South Australia. This picture: Angela Skujins

Jamie Hampton is a Warlpiri man from Yuendumu in the Northern Territory’s Central Desert Region and a staff member at the State Library.

He has been tasked with helping the institution repatriate items taken or acquired from this community group decades ago.

Jamie says the State Library has Warlpiri crayon drawings and sound recordings, as well as “important cultural material” surrounding family histories and photos of deceased community members.

“I used to come into the library and just engage with the collection, go into the reading room and have a look and use the online catalogue,” he says.

“And then when I realised the extent of what was here, I started going back to community and just saying, ‘There’s stuff at the library, and there’s a stuff at the museum’.”

Most of the State Library’s Warlpiri material is located in the Mountford-Sheard collection, named after South Australian ethnographer Charles Mountford, who in 1925 transitioned from telephone mechanic to amateur anthropologist.

In 1951 and 1959, Mountford travelled to Yuendumu to try to gain an understanding of Indigenous myths and cave paintings.

Some of the Warlpiri material collected by the ethnographer, and donated to the State Library by his colleague Harold Sheard, includes photographs and films.

Geoff says ownership of this material is easily defined, as “they weren’t obtained unethically”.

This isn’t always an easy distinction to make.

In the instance of the crayon drawings, recorded on materials Mountford provided to the Warlpiri community, the Indigenous artists are considered the authors.

The artworks were given to Mountford’s touring party, but Geoff says there is no recording of “how much consent was given” during the handing-over process.

“Talking about cultural endeavours, like painting, drawings, photos… they’re cultural artefacts that I think came to us via a donor, but that donor may not have had the rights to necessarily donate it,” he explains.

“We do need to have a look at what was the consent or the sense of the fact that they were taken away and then held by us.”

Warlpiri elder Warren Japangka Williams has been part of this process.

He has twice travelled 1826km from the centre of Australia to the State Library of South Australia, with other male elders, to examine items that will eventually be repatriated.

“We told [the State Library] that we want them back in our community,” Warren tells CityMag.

“They’re more than willing to let us take them, and they’re helping.”

View this post on Instagram

The State Library is working on a five-year plan to establish an Aboriginal-controlled cultural centre in Yuendumu to store the fragile archival material once it’s returned.

One of the major challenges for returning artefacts to the communities they’ve come from is housing them in appropriate conditions.

For example, film requires a climate-controlled room, held at a temperature below five degrees with low humidity.

Another challenge is staffing these centres with workers qualified to handle the delicate materials.

Geoff says the State Library wants to invest in Jamie – an Indigenous employee with “deep cultural knowledge” of the area – to become one of the many qualified experts.

“At some stage that may see Jamie back on country, exercising those skills to be able to continue to be the continued link with his collection,” he says.

Despite the work being done to extend custodianship of these artefacts back into Indigenous communities, the State Library still seems reluctant to cede too much control.

Geoff says the Library holds onto artefacts because of a lack of appropriate facilities (as mentioned above), but also because the institution studies the documents.

But he says there are processes in place to ensure shared access.

“We’re really keen to do digital repatriation first up,” he says.

“So that gives the community digital access to the content that we hold, while it remains in custody in a safe place.

“Then over time, we can repatriate some material, which are reproductions of some of this content.”

Warren is looking forward to all the pieces of the Warlpiri history being returned to country.

The young kids in his community want to know where they come from.

“In the past, I don’t think the library would have let us take anything away,” he says.

“This is a great step towards reconciliation. We never saw this coming.”

This picture: Angela Skujins