In an age of constantly shifting priorities, artist Kirsty Martinsen’s ‘Our Lady: en feu’ brings attention back to earlier global catastrophes.

Don’t forget, the world is on fire

On the blank walls of The Mill’s gallery space hangs Kirsty Martinsen’s latest exhibition – Our Lady: en feu.

From wall to wall there are images of smoke and fire, all together creating a narrative of landmarks marked by flames and landscapes reduced to ash – chaos, in a word.

Our Lade: en feu closes on Wednesday, 29 July. Get in to The Mill to see the exhibition while you still can, or view it virtually at the link below.

The Mill

154 Angas Street, Adelaide 5000

Exhibition info

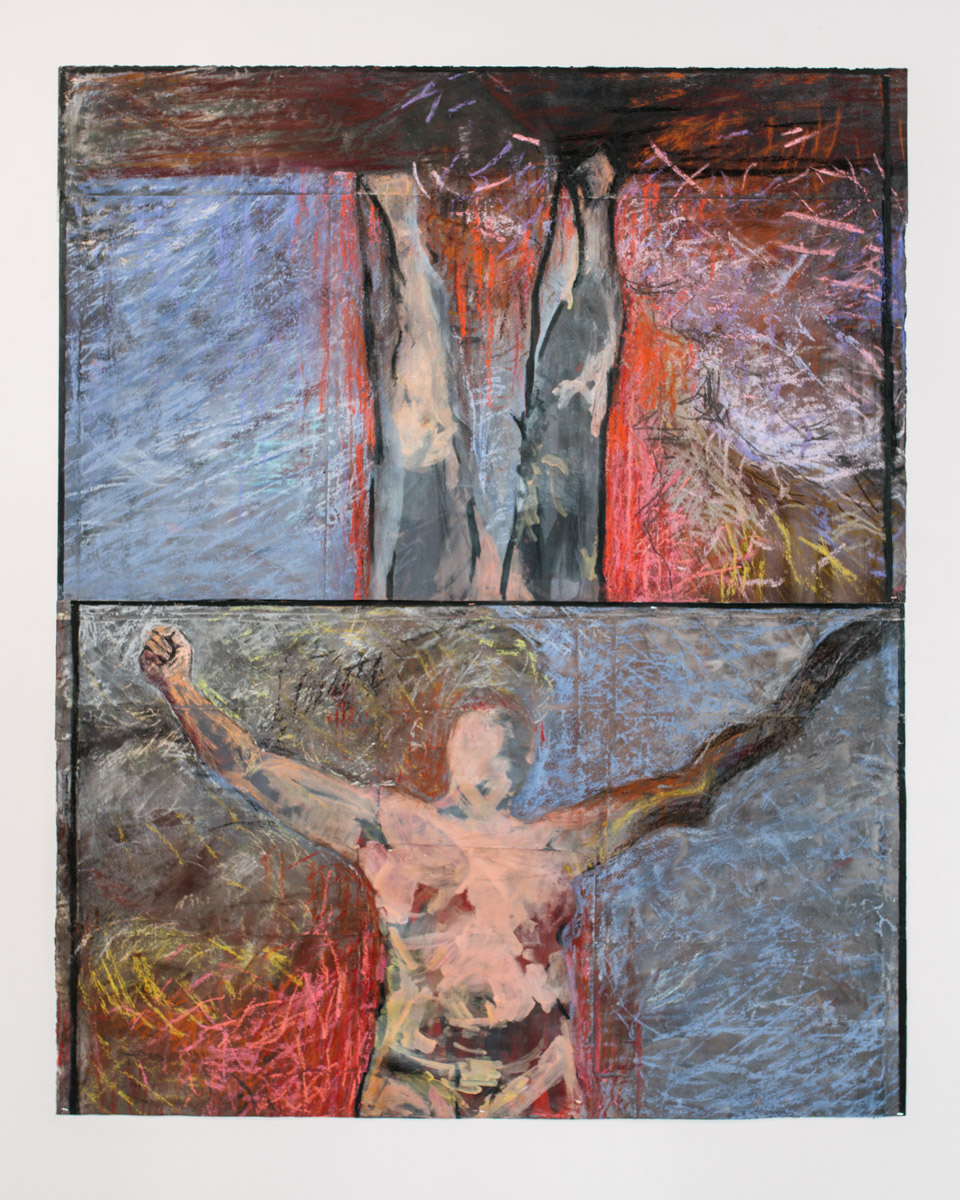

The exhibition began as just one painting, the woman on the northern wall, her legs disembodied above her head, her torso below, with arms splayed in a crucifixion pose.

This piece began in 2008 as an exploration of how the world may be different if Jesus Christ, as we known him in Western Culture, was conceived in our minds, instead, as a woman.

For years, the work sat in storage amongst many others, before being uncovered over a decade later, with Kirsty seeing the piece with fresh eyes following the #MeToo movement.

She returned to work on the painting, and around this time, early in 2019, fire broke out in the roof of Notre Dame, in France, making news around the world.

Kirsty noticed two things: firstly, the images printed in news media of the cathedral burning were visually stunning; but secondly, the global outpouring of grief was immense.

“People were just responding in this really dramatic way – overly dramatic way – to something that was just a church, you know?” Kirsty says.

“People were like, ‘No! It’s a symbol of France.’ Really?

“People were placing so much value on a church when there was so much else going on in the world that was destructive and needed attention, but everybody was just freaking out about the spire burning.

“That’s when I started to think more about destruction and questioning the values of the world we live in, basically.

“And the fact that they called the upper floor [of Notre Dame] the forest, I just thought, you know, the Amazon has just been burning, and the Amazon is considered the lungs of the Earth, so the forest burning is like Mother Earth is on fire, and so I saw it as a metaphor for climate change, and our world is on fire.”

Smoke and fire began to billow behind the woman crucified, as it is seen today.

On the exhibition’s eastern wall, Our Lady: en feu has many studies of the Notre Dame fire. These are mostly calm scenes of contained chaos.

Later in 2019, at the end of the year, fire would once again become a dominant presence in news media, as the summer bushfires stoked across the country.

In contrast to the images of Notre Dame, Kirsty’s works on the wall opposite portray the bushfires from a perspective deep within the chaos.

“I was a part of Ash Wednesday in the ‘80s, and our house nearly burnt down, we were in the middle of it all,” she recalls.

“So to see bushfires happen just brought back all of those memories… I was in here working… while it was happening, because I just felt like I had to have an immediate response to what was going on, just because of the emotion of what it brought out in me, and the connection to climate change and [humanity’s] attitude to the environment.”

Flames engulf the entire work. Even the portraits of native flora paint a grim picture of an Australian landscape destroyed by fire.

Through this exhibition, Kirsty hopes people will consider what is valuable in their lives, and whether the interests of our society, as portrayed in media, both traditional and social, marries with this idea.

Is the burning church the best use of the limited real estate of a newspapers front page, and could the millions of dollars in donations from wealthy benefactors be better employed in other parts of society?

Yes, the many bushfire appeals raised millions of dollars, but the #MeToo movement, particularly in Australia, where defamation laws have proved to be effective barriers against meaningful change, is a dying ember desperately in need of oxygen.

Kirsty chooses not to be prescriptive in how she wants her work to be interpreted, but she does hope it prompts such questions.

After destruction – by fire or by pestilence – there is an opportunity to reconstruct anew.

This is exactly the time to be examining what it is we as a society value.