Although it is hard to define, partially presented in Portuguese and concerned with themes as big as reality itself, the latest film project from Adelaide’s Tyrone Ormsby is intensely compelling.

A dream of reality

Tyrone Ormsby – a graphic designer and filmmaker – started work on his latest project almost entirely by accident.

“I was living with a performing arts collective in Portugal… and they got a new job – a paid professional job. So, I just went along one day to sort of see what they were doing and I ended up staying for four months and filming everything,” he says.

Tyrone is now near to completing the process of whittling the copious amounts of resulting footage down to a 60-minute (or so) film that straddles documentary and fiction. Called ParaMim, the film is built around his recording of the rehearsals and performances of theatre play La Vida es Sonho (Life is a Dream) by leading Portuguese production house Companhia João Garcia Miguel.

The play itself is an adaptation of a 17th Century Spanish work that wrestles with issues of reality, dreams and existentialism through the story of a man locked in a tower because a prophecy foretold that he would bring about the downfall of his father’s kingdom.

Upon completion, ParaMim will be entered in some documentary film festivals and then will be made available for viewing online.

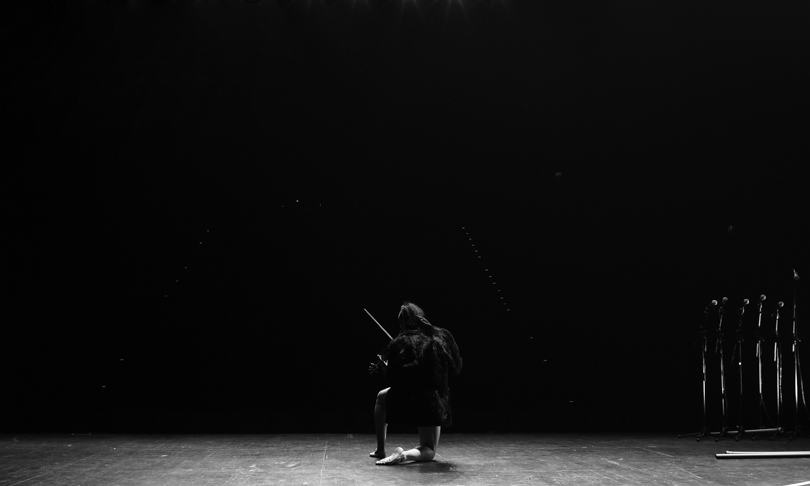

At it’s most simple, Tyrone’s film chronicles both the creative process involved in mounting the play and presents a condensed version of the final piece. But, really, ParaMim is far from simple. Through switching perspectives and focusing on particular details, it creates an atmosphere in which the viewer begins to question their own point of view.

“My goal is to challenge the viewer, to twist the viewing perspective by offering alternate realities within the film.” says Tyrone.

“I would say that the first perspective [of the film] is my universe of the play, and then we move to the director’s creation, and then into the actor’s personal spaces both within the play and personally – the film moves between all of those.

“And it starts to tell a different story, because once you film something and you frame it, you begin to see abstract relationships between elements that were not designed for the intention of a film — because you’ve captured it, you have the privilege of seeing and contrasting these elements differently.”

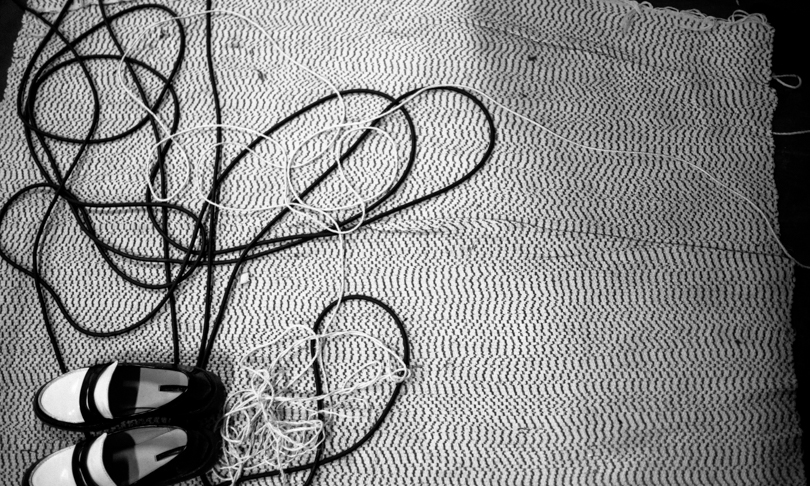

ParaMim encourages the exploration of these new focal points using an arresting black and white aesthetic that partially recalls film noir, but also invokes an understanding of time’s elasticity by seeming to speed it up and slow it down.

Filmed entirely by Tyrone himself, this visual feel evolved alongside the concept of the film.

“In the first round of rehearsals and when I didn’t have this idea to make a film yet, I was just hand-holding the camera, filming everything, and it looks like something the director would just use as a reference” says Tyrone.

“I stopped doing that after a month and a half and started filming really intensely, trying to get the framing exactly right – I began trying to capture my own compositions from Joao’s scenography of the stage.

“And after that I started to understand the project, and it gave me the freedom to be more creative with it. Because I had points of reference, these two very distinct folders full of information, I started to work on some of my own interpretations of the play. That’s where the three perspectives in the film surf in and out of one another.”

Asked by João Garcia Miguel, the director of the play, to “just do whatever you want and make sure you show me something that I didn’t get to see over the last five years working on this”, Tyrone has been striving to bring something entirely new to life using elements of something existing.

It’s a hard task, and one he’s struggled with at points as he works through the initial stages of editing with only the help of a handful of mentors.

“It is when you get to a stage of a project and you feel really overwhelmed, or you wonder why am I making this?,” says Tyrone.

“Documentaries are usually going to have a political or social benefit other than entertainment, and you get to this point where you question that what you’re doing is relevant.

“But I like that cynicism, because it means after that self questioning, when I have decided to keep working, that I do really think this is a good project, and I think it will be beneficial for people, to put the questions presented in this work into their own life, it might spark something for them – as the original did for me.”