The fragility of language, humanity and the Australian landscape are all explored in three new exhibitions just opened at FELTspace.

Breaking apart

It’s a bitterly cold night as I make my way to FELTspace gallery. The air is like ice against my face and my breath hangs in front of me like a vaporous spectre. It is a proper July night in Adelaide, where ears and fingertips are gradually numbed by the world.

Fortunately, the gallery itself exudes warmth and there is a welcoming hum of conversation. The cold moves from my bones and skin as I recover from the elements.

With fingers still aching, I am struck by an immediate sense of vulnerability in Bernadette Klavins’ work Vast Spoils, which offers a god’s eye view of a rich and detailed sculptural landscape.

Quarries, crevices and embankments stretch out over the gallery floor. Delicate contours and curves as well as barbed edges and sharp, abrasive lines. This is a land of extremes.

The viewer has a privileged perspective, the ability to survey everything all at once or to zoom in on minute features.

There is a feeling of vulnerability in these sculptures. They seem precarious in places, but also strong and defiant. In one piece, stones dangle in the air like fragile, weightless pebbles from outer space, gradually ascending into the void of infinity. In another, jagged rocks protrude from the heavy earth like rebellious monuments.

Some of the impressions are like scars or wounds, deep fissures in varying states of healing and repair. The landscape that the artist presents is like a vulnerable body, but it is not doomed. Scars indicate that there was a physical trauma, an injury, but they also show us that there was healing and recovery, that rescue is possible. Scars become memories of survival and strength.

I find myself thinking about the inescapable nature of human vulnerability, the potential to be injured and harmed. These sculptures capture the further idea that something vulnerable can be saved. It is not the mountaineer clinging to a cliff’s edge with a fraying rope. This mountaineer is doomed. As the cable inevitably snaps and the mountaineer plummets, they are beyond salvation, they are condemned.

These landscapes are salvageable, like a survivor dragged free from a burning building. There might be trauma here, but Bernadette’s landscape feels robust enough to endure, as though there is power and determination in the lustrous soil.

In Tending Toxicity, by Dan Schultz, Otis Filley and Michael Ross, the vulnerable and the doomed are juxtaposed from one another.

Three large screens and a set of artefacts tell a story of drought and suffering. There is a rusted child’s bicycle suspended from the ceiling like a decaying puppet. There is vision of a turtle lying dead in the mud being devoured by small bugs. But there is also a scene of rescue, as a mythical looking horned beast is dragged from mud that looks to be the consistency of wet concrete.

Brutality and peril exist in this battered landscape, but there is also energy, life and hope.

In Tending Toxicity we see our own vulnerability reflected in the landscape. Vulnerability is not a mere label here, nor is it a negative notion, a sign of weakness or frailty. It gives us power.

Without vulnerability we cannot be open and honest about the need for change. As we respond to climate emergencies that threaten to occur again and again and again, there is acknowledgement here of the need for collective social action to save humanity and repair our home.

A policy document buried in ash sits in the corner of the room, but there is hope here, optimism. Art becomes social action, a call to form a collective capable of mending the land and ourselves.

Connal Lee has a background in philosophy, a PhD in applied ethics, and works as a freelance writer and as a lecturer in health ethics at UniSA.

He has published work on utopian thinking in political philosophy, the relationship between art and wellbeing, and developing moral imagination and empathy through stories and storytelling.

This piece was contributed as part of FELTspace’s FELTwriter program. For more information on the program, see the website.

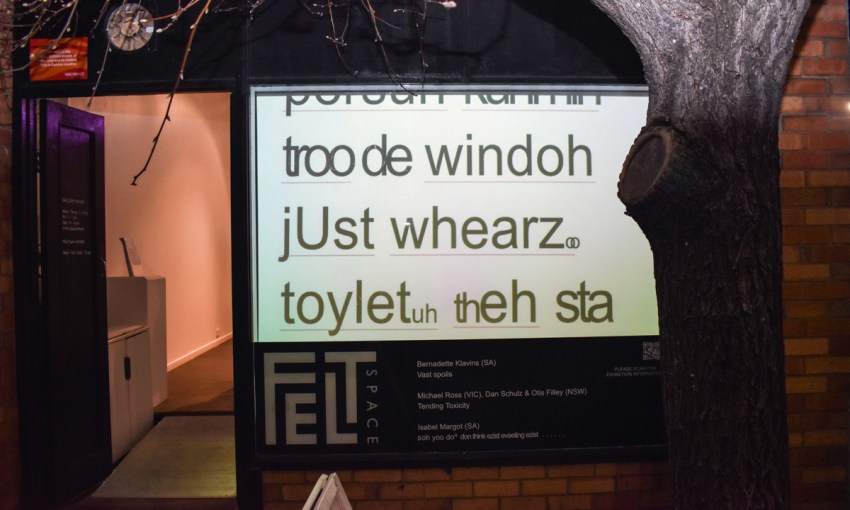

Back outside, the night has grown colder. The air is crisp and intense. In the gallery window, Isabel Margot’s work soh yoo doⁿ don think ezist eveeting ezist . . . . . . offers an existential glimpse into language.

This work feels like a Turing test designed by James Joyce, an engrossing exploration of letters and their form. As I found my mind looking for familiarity and recognition in the shapes, I started to think I was in dialogue with a piece of artificial intelligence trying to convince me of its consciousness.

There is something about the nature of language in this work. The grammar is destabilised, disrupted and reconfigured. The work reveals to me the desire of the human mind to search for coherence and meaning, to enforce concepts or narratives on randomness.

Like the landscapes in the other works, there is a feeling of unrest and turmoil, but there is also a beauty to these damaged and fractured forms. Perhaps it is from deconstructing things that we discover their true essence.