The retail industry is undergoing huge pandemic-induced shifts. We spent time imagining what the future of Adelaide's premier shopping district could look like.

The future of Rundle Mall

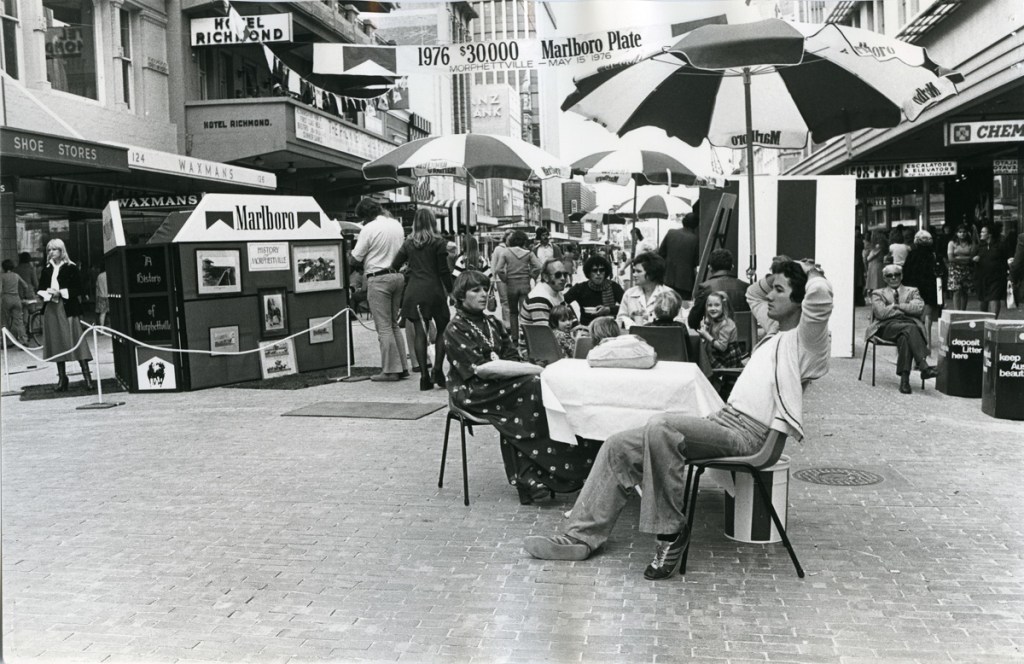

A motorcycle rider with chops and a studded leather jacket dunks his helmet into the recently installed Rundle Mall fountain. Around 20,000 people – including Premier Don Dunstan – are squeezed onto the 528-metre-long strip.

They watch as the biker brings his helmet to his lips to sip on the sweet champagne. It’s 1 September 1976 and the revellers in Rundle Mall are celebrating the shopping district’s official opening. To mark the occasion, the fountain flows with sparkling wine.

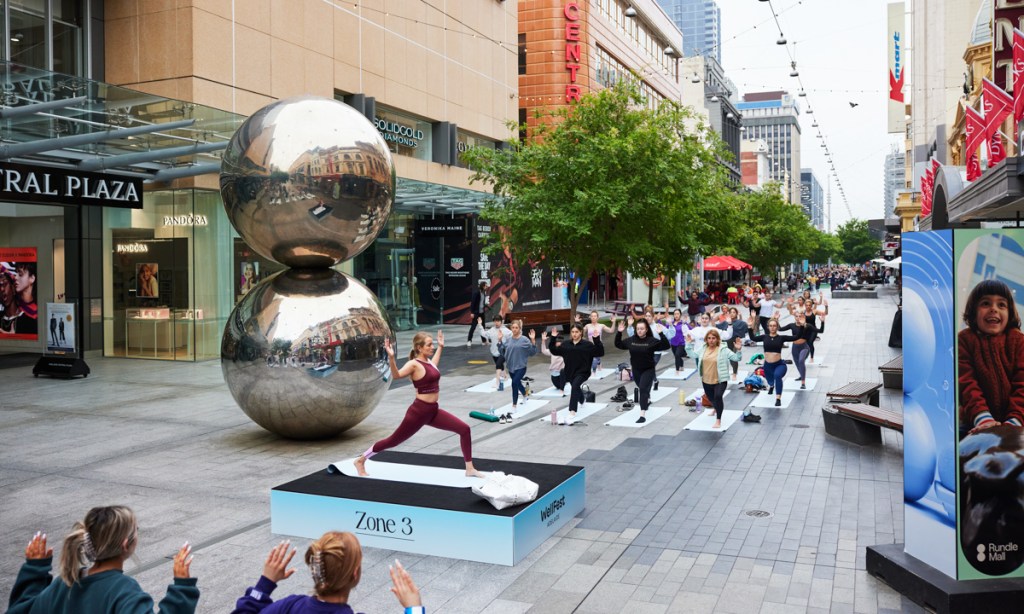

In 2022, 46 years after the street was closed to cars, the Victorian-era fountain is missing from the Adelaide Arcade entrance, taken away to be restored. In its place, national sports brand Rebel Sport has set up an ‘activation’ where people can shoot hoops. Rundle Mall hosted 230 similar activations last year.

Nearby, the recently opened Million Life arcade buzzes with bright and loud machines. On the two occasions CityMag steps inside, the shop has no employees. Further down the Mall, customers stream in and out of Woolworths, where CCTV cameras track trolleys, the contents of which will be scanned by customers moving through self-checkouts.

Rundle Mall, one of the largest outdoor malls in the southern hemisphere, has changed significantly throughout its lifetime. It’s now home to roughly 700 retail stores, 300 service businesses (such as cobblers or iPhone repair shops), as well as the staff who fill them.

It is all at once a place to shop, to pick up lunch or sit in for dinner, a host to performers and art installations, a place to meet, and, if you’ve got nothing else to do, simply loiter. It’s the entire city in miniature form, and, like its extrapolated synecdoche, is in a period of recovery.

A modern-day yoga activation by the Balls. This picture: Andre Castellucci

David Jones sales assistant Christine Mitschke has seen a good chunk of Rundle Mall’s history. She started as a Christmas casual 21 years ago, working in the upmarket department store’s computer section. Pushing a strand of greying black hair behind her ear, Christine – who now works in tabletop and homewares – says she remembers her first day being awash with kids. “The Magic Cave is up on third,” Christine says, “so the kids were excited.”

Back then, store policy was to refer to customers by their surname, but Christine was so personable people would often ask her to call them by their first name. She still has this professional panache decades later. “I have a couple of people that wait for me or they ring to find out when I’m in so they’ll come in on that day,” she laughs. “They may be looking for a product to see if I’ve got it, but then obviously sometimes coming in to have a little chat as well.”

However, according to research conducted by McKinsey Global Institute, shopping is set to become much less personal. They found half of all retail activities could be replaced by machines, though senior marketing scientist at the University of South Australia’s Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, Bill Page, is confident not all retail workers will be replaced by technology. “You need people to tidy up,” he says. “You need people to make sure that the shelves are stocked, you need people to give advice.” Still, automation comes in sneaky ways. Bill points to how supermarkets have replaced checkout chicks with self-checkouts.

A lot of our shopping activity no longer takes place in the physical world. Australian online retail trade peaked at $4.3 billion in September 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The Adelaide Economic Development Agency (AEDA) recently launched byADL, an online marketplace featuring the city’s retail stores, making Rundle Mall evermore digitally accessible. Despite this, Bill reckons online shopping will never totally topple “flesh-and-blood” shopping. “There’s a lot to be said for how quickly you can process things in the real world versus a picture of it,” he says.

Shopping irl is good too. This picture: Dimitra Koriozos

Bill is less optimistic on the long-term effects of the pandemic on the city. As people have gotten used to working from home, they’re also becoming more closely acquainted with the shops in their local area. This does not bode well for the city, he says, as the options available to shoppers on their days in the office will be less front of mind. If trading conditions remain tough, Bill sees Rundle Mall becoming dominated by conglomerates. “As bigger companies have expanded and expanded and expanded globally… if you were picking places to put a store in Adelaide, Rundle Mall would be one place,” he says.

AEDA’s executive manager for Rundle Mall, Andrew White, celebrates the strip as the “first” state location for many international labels, such as H&M, TAG Heuer and Uniqlo. These shops give the precinct a strong point of difference, he says.

In turn, these bricks-and-mortar stores are creating their own points of difference to lure in shoppers. Andrew references the aforementioned basketball hoop as an example. “Experiential retail is the future of retail,” he says. “You only have to look at places like Rebel Sport and their experiential retail offering, or Dymocks, to know that customers want something more than just a retail transaction.”

The largest shopping centre in the city, the Myer Centre, spans 60,000sqm over five floors of retail space – much of which has emptied in recent years. Social media abounds with the public’s lament of the ‘ailing’ building. Shoppers still mill on the ground and mezzanine floors and the food court can pull a crowd, but from level one up retail is sparse.

It was once home to a singular example of experience-based shopping: the short-lived but long-remembered Dazzeland. The indoor amusement park launched with the Myer Centre in 1991, occupying the top two floors. There were arcade games and rides, including a roller coaster that skirted and crossed the atrium. Kids on school holidays would drag their parents to the top floor, passing every retail layer on the way up. The fun lasted until 1998, when the park was shuttered.

New major tenant Uniqlo is now installed in the building and there is an abundance of vacant tenancies above it. Conditions are perfect for a Renew Adelaide intervention. The organisation has filled vacant shopfronts across the city for a decade, including in the Myer Centre. In 2021, the space that is now Uniqlo hosted two fashion startups, Nixii and Moral, and a third, Uncle Mack’s, opened on the basement level. All of these businesses have moved on, but Renew has another three spaces in the building under its purview.

Renew Adelaide CEO Gianna Murphy recalls the halcyon days of the Myer Centre, a time when customers venturing upstairs was not considered outlandish. “What I remember is that there was never any question about shopping up,” she says. “There is a real phenomenon in Adelaide where we just don’t want to shop up or down.

“I think that the only way that we can bring people to upper levels, as we did 20 years ago, is have something really interesting on those upper levels that’s a real destination place.

“Whether they can do Dazzeland again, I don’t know, but a modern take that’s interesting and interactive, and family-friendly, I think is important.”

When programming the level one spaces, Gianna chose businesses that are not a “straightforward retail offering”. Instead, they “offer something a little bit more interactive”. One of the businesses is a costume maker, for example, who’ll also have a photography space for cosplayers.

Gianna hopes Renew’s relationship with the Myer Centre will continue and expand. She has a list of 430 ready-to-go business ideas and says she could “fill the Myer Centre entirely… tomorrow”. But in an online shopping world, it’s not realistic to expect retail alone to fill the floor space it once did. “I don’t think you’ll ever have a Sportsgirl or a Cue or a Zara up on a level four. It needs to be the right type of tenant,” she says.

View this post on Instagram

If you’re looking for a radical vision of the future of the Myer Centre, Studio Nine Architects director Andrew Steele has one.

“If you had a choice, you’d detonate the whole building,” he laughs. “I’d blow it up and start again. Do it properly.”

Opinions on post-modern architecture aside, Andrew agrees we won’t see multi-level retail dominate the Myer Centre any time soon. “There’s plenty of examples where that’s done well. But unfortunately, with where we’re at as a state, I just don’t see it, in the shorter term, being a success, until we get enough mass behind us to attract the bigger players,” he says.

Andrew Steele

A more interesting – if expensive – solution, Andrew says, would be to cap the central atrium at the level retail stops being successful and open the rest of the central space to the natural environment. This would allow for the building’s conversion into a hotel. “Just the location and the views you’d get there would be amazing, and the proximity for all of the other stuff that’s going on in the city,” he says. The cost, though, is a problem – particularly when pitching the idea to a foreign owner. “It makes complete sense. Why hasn’t somebody done it? Because it doesn’t stack up,” he laughs. “When the spreadsheet behind the design doesn’t give you a green number in the bottom right-hand corner, you’re not going to do it.

“They don’t hear what the local news articles keep saying about [the building] – they don’t care. They’re in Singapore. Why would they?”

The most likely (read: cost-effective) change, then, would be a remodelled façade, which, to Andrew, is “a lipstick on a pig scenario”. Though he has ideas here, too. He’d like to see the bulky shops obscuring the entrance reconfigured, allowing elements of the Mall into the centre.

“They’ve tried to increase the net lettable area by pushing retail out to the edge of Rundle Mall, which means you walk past a whole heap of built form,” Andrew says. “The actual apertures to get into the Myer Centre are actually relatively narrow… so how could you remove some of that bulk down on ground level and bring the Mall in, and then bring it up?”

During CityMag‘s research for this story, a black-and-white photo landed on our desk. It was a snapshot from 1987, showing roughly 50 school bags piled shambolically outside Sportsgirl. Shops along the strip wouldn’t let kids bring their backpacks inside.

The Sportsgirl outlet has since closed, it’s where Glue opened in May last year, but this churn shows that, through the oscillation of intermittent investment and neglect, there will always be crowds coming through.

There will always be people willing to be pulled into a place like the Myer Centre, if there’s a basketball hoop, champagne-filled fountain, or considered retail experience worth travelling for.

Just a shady place to sit will do. This picture courtesy City of Adelaide Archives