To Primary Industries Minister David Basham, whose family has farmed dairy for six generations, some plant-based meat substitutes taste like “cardboard”. But his government wants South Australia to be a major competitor in the emerging plant-based food market.

Inside Adelaide’s new $2m plant-based food incubator

Last month, the State Government announced it would pump $2m into establishing a plant-based food incubator laboratory in Adelaide.

The State Government’s plant-based food incubator aims to be operational by April 2022.

CityMag recently toured the nascent facility, located at the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) at the University of Adelaide’s Waite Campus, which was allocated the funding to help support local brands entering the booming plant-based food production industry.

A recent study, conducted by national plant-based food accelerator and think tank Food Frontier, found one in three Australians is consciously limiting their meat consumption, while 10 per cent of the entire population eats an entirely meat-free diet.

South Australia’s Primary Industries and Regional Development Minister, David Basham, says there’s “great opportunity” for local businesses to tap into domestically grown crops and pulses – such as fava beans and lentils – to do this.

“There’s great opportunity for people to tap into this resource, develop products, [and] for it to be South Australian-based, if that’s the logical place for that investment to occur,” he says.

While starting any new business is challenging, there is a particularly difficult “gap in the middle” between inception and commercialisation, the minister says.

Flush with machinery and technological expertise, the plant-based incubator is intended to support businesses in bridging that gap.

“A business needs to invest in that space to move from just kitchen experiment through to production. It’s a very different and expensive process,” Minister Basham says.

“The opportunity here is… for that to happen in a supported environment, rather than a business saying, ‘Well, I’ve got a really good idea. What I’ve [created in] the kitchen is exactly what I think the market needs. Now let’s go out and spend enormous amounts of money to risk getting to the other side’.”

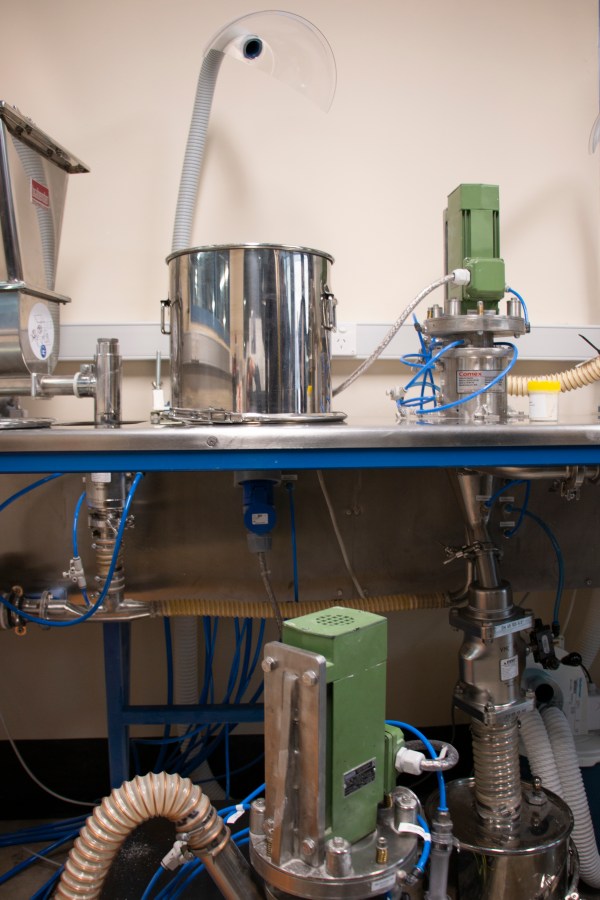

With its $2m, the incubator lab has purchased food production machinery, such as extruders, which transform ingredients into particular shapes; protein analysers; drying equipment; and ultra-high-temperature processors. Most of the gear is destined to arrive this month, with the facility set to be up and running by April 2022.

SARDI’s food sciences research director, Maria Saarela, says the incubator is not intended to be a commercial-grade production facility, but a space to help brands with pilot products. This could include snacks, fake meat or milk alternatives.

“We will make the prototypes for the industry,” she says.

“With plant proteins, there are lots of challenges of how to incorporate that into the food, because they behave so differently from animal proteins like dairy proteins.

“Animal proteins, from a technical point of view, are much easier and nicer to work with.”

The fractionator: Machinery that separates food components

Another challenge when developing a plant-based product is taste. Legumes have a “bean” flavour, which may be too off-putting to a meat-eater, Maria says.

“You should be able to achieve both, reasonable price and good taste,” she says.

“It’s a very small part of the population that is willing to compromise those two.”

Minister Basham worked as a Fleurieu Peninsula dairy farmer for three decades before becoming a politician. He has reconciled his current seemingly contradictory position as a supporter of milk alternatives, he says, by maintaining an emphasis on the word ‘alternative’.

“Good food is always so important, but I think it does need to be clearly understood that these are alternatives. They’re not necessarily replacing, they’re just another option,” he says.

“We see this as a growing sector from South Australia, to produce more meat protein or plant protein resources to the world – to feed the world.”

A study, published in 2013, suggests that if global crops were solely dedicated to human consumption, as opposed to 36 per cent of the calories grown worldwide becoming animal feed, the amount of food calories available for humans could increase by 70 per cent, allowing global crops to feed an additional four billion people.

Another 2019 study found that avoiding meat and dairy products is the single biggest way a person can reduce their environmental impact.

The number of Australians actively eating less meat (or abstaining entirely) noted at the top of this article suggests this research is having an effect.

Even Minister Basham admits to sampling the occasional vegan hotdog or hamburger.

“At different times there are some things I’ve happily enjoyed and there are others where cardboard might be nicer to eat,” he laughs.

The Minister believes as the industry grows, so will commercial investment, to the tune of an estimated $240m.

“[Food businesses] will take those ideas from the kitchen, put them through this process, get out the other end a product they think is commercialisable, and go and commercialise it and put the investment into their own facilities to develop,” he says.

Any business looking to pilot a new food product in the incubator lab should engage with Food SA.