Not-for-profit Drop In Care Space is a volunteer-run community initiative that offers resources, activities, and, above all, a safe place to hang out.

Inside the community drop-in centre putting lived experience first

CityMag looks across a wide, sun-filled yard at a weathered building, brick and concrete visible under chipping and fading paint. Splashes of bright colour frame the doors and windows.

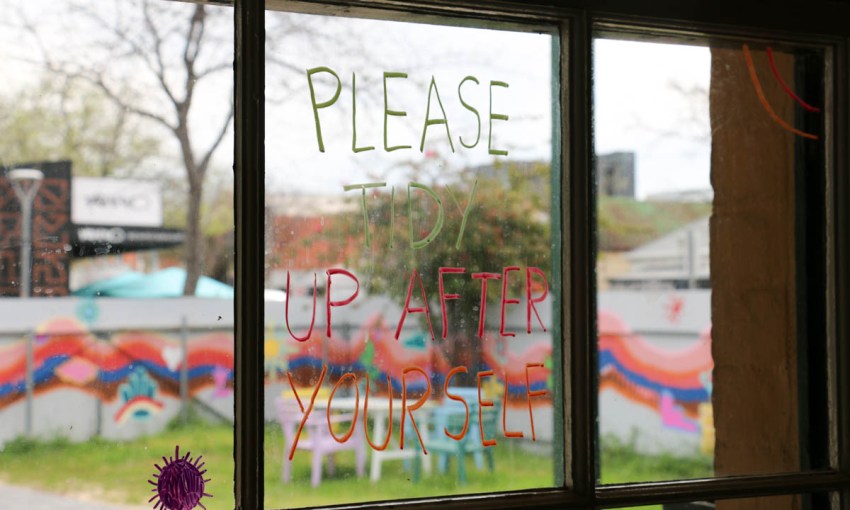

Although there’s a yellow sign with colourful text by the entrance, we can’t shake the feeling of being over at a friend’s.

This “second home” feeling is exactly what not-for-profit Drop In Care Space is going for, according to founder and director Sonny Jane, who waves to us from a huddle of couches and armchairs.

Although the Care Space now has all the trimmings of a fully-fledged home – complete with a neatly-stocked kitchen, an almost-finished 1000-piece puzzle and well-resourced bookshelves – it operated out of the living area of Sonny’s private counselling practice on Hindley Street until the start of this year.

The community initiative launched in a pre-pandemic 2020 to help people aged 18 and older connect and “relieve distress and isolation” – a goal which has, according to Sonny, only become more relevant.

These days, the volunteer-run centre – open Wednesday to Sunday – offers peer support, resources and activities, with a focus on leading from experience.

Sonny says autistic, queer, trans and disabled people, who could be “missing these community spaces”, are often referred to the Care Space by other community organisations.

The Care Space’s broad target age group means they attract people in their early twenties, thirties, and occasionally forties, some of whom are transitioning out of organisations like the Queer Youth Drop-In. “Adults need community too”, Sonny says.

Drop In Care Space’s Sonny Jane

CityMag speaks to Sonny in the Yellow Room, with a variety of posters lining the walls – which Sonny describes as reminiscent of a bedroom. This room, like others in the building, is colour-themed, so as to move away from “sterile and impersonal” clinical settings.

It’s no accident the Care Space’s Green Room is the movie room – Sonny, like CityMag, enjoys a good pun.

Signs of Care Space’s ties to the community are everywhere. In the Purple Room, CityMag recognises a print from artist Judy Kuo. Denise Nolasco, Care Space’s co-director, says Judy was one of many artists she was able to purchase through a grant to fill the Care Space with “projects related to nurturing an anti-racist community”.

“With what little funding and resources we have, it’s important for us to inject those resources right back into our communities and support the folks who lead with a lived-experience lens,” Denise says.

Even the fence outside features spray-painted designs by Youth Inc. students.

Despite the colourful veneer, the Care Space was set up to address serious shortfalls in community-oriented mental health care, Sonny tells us. In their previous role as a counsellor, they spoke with many people who felt disconnected from the community. Sonny can relate to this.

“Growing up, I didn’t really have access to community or a home that looked like this, or, you know, [a place] where I could meet like-minded people,” they say. “Or feel safe or explore activities or even meet up with friends that didn’t revolve around alcohol in public places.”

The Drop In Care Space often gets referrals from the Urgent Mental Health Care Centre, Sonny tells us. They hope providing a space “free of judgement” – where people can access resources and develop tools and strategies – will reduce the number of people reaching a crisis point.

They say the role of non-clinical spaces is often overlooked in the conversation around mental health, which “focusses on therapy and medication”.

“Creativity and building relationships and having a safe space to come to are just as crucial to our wellbeing,” they say. “I’ve always felt peer support and our lived experience can be valuable on its own.

“People with lived experience are the real experts of their experiences.”

Sonny uses the example of a person with ADHD having trouble cleaning their room being told by a clinician without ADHD to “break down the task into steps”.

“Whereas someone with ADHD would be like, ‘No, ask a friend to come over, and that will motivate you to clean your room’,” Sonny says. “How we do things or how we work through things is vastly different.”

Much like with everything else at the Drop In Care Space – or DICS, as it’s cheekily known – daily activities are planned in consultation with peer volunteers. CityMag times our second visit, conveniently, on board game Sunday.

Peer volunteer Isa is a patient guide as we join in on a heated game of Organ Attack with the other volunteers, Alec, Jace and Serena.

After the game, Alec tells us apart from facilitating activities and maintaining the space, peer support requires being “flexible to change”. This could mean running multiple activities at once while meeting various accessibility and sensory needs, Alec says.

“Even though I’m working I’m still able to have that social aspect,” he says. “So it’s very much like taking care of myself while taking care of others.”

And for those who need “downtime”, Jace says, the Purple Room is tucked away, with the blinds drawn to reduce sensory input.

Jace sums up the peer support model as something that’s “constantly moving, like a giant spider web of love”. He says for people like him who “struggle to get out of the house without a specific purpose”, the Care Space is mutually beneficial.

“Even if there are only the volunteers here on quiet days, you’re still with other people, you’re still body-doubling, you’re still learning something,” Jace says. “And it keeps that routine of allowing us to be functional people in a society that is not built for us to succeed.

“A lot of us struggle to keep steady employment in neurotypical-run environments. This gives us basic foundations for us to continue on and prosper out in the very scary, big world.”

Without calling into question the merits of a game of Organ Attack, the space also tailors activities to the community’s diverse needs. Sexual Health Week, for example, featured activities on topics like sensory play and disability and sex.

“When it comes to sex and sexual health, you know, our autistic needs are often left out of the conversation,” Sonny says. “Same with disability and sex – disabled people are infantilised and they don’t really see us as having sex, which is obviously so far from the truth.”

Denise says she was drawn to co-directing the Care Space because Sonny was “leading from experience”.

In her previous role at another not-for-profit organisation, Denise – who is a second-generation Filipino Australian – says she found many young people felt like their stories were siloed.

“I think just opening up that conversation with people helped them realise that while our stories are super unique that doesn’t mean that other people won’t understand them,” she says. “It doesn’t mean there aren’t parallels.”

One such “common thread” between her and some of the people she helped support, Denise says, is that they had all grown up in “predominantly white spaces” and didn’t feel as connected to their “person-of-coloured-ness”.

“But not connecting with your person-of-coloured-ness is a valid story,” Denise says. “It doesn’t make you less of a person of colour.

“Different ways of being need to be acknowledged.”

Denise says having someone with lived experience to speak to about navigating complex identities can minimise the “laborious energy” of having to explain yourself to someone who is “meant to be helping you”.

In a former role, Denise noticed that the lack of non-white employees in leadership positions meant the organisation she worked for had a limited understanding of the people they were trying to support.

She says this urge to “do better” in the not-for-profit sector led her to Care Space.

“Folks who work in social services often create ‘multicultural programs’ without the lived experiences of people of colour at the centre of these programs,” Denise says. “Here at the Care Space, everything we do is lived-experience-led.

“We meet with our peer volunteers on a regular basis and make sure the activities we offer are activities folks actually want to lead and participate in.”

Serena says the beauty of peer support is that they all draw from “different lived experiences”.

“We can all uplift and try to support one another where it’s appropriate within our scope, and then be able to have resources available if needed,” she says.

Tools to do this while avoiding “pathologising” language is part of the peer-support training, which Sonny and other board members lead.

For Serena, a key takeaway from the peer training is being accountable while “knowing that you’re not going to always know something”.

“As long as you’re willing to grow and accept new ideas, or challenge your own biases and opinions, then you’re welcome in the space,” she says. “We’re all going to mess up at one point, but it’s how you come back from that.”

In keeping with this, the Care Space is “always changing, always adapting”, Jace says.

“And always willing to learn and grow as well,” Alec says.

“Anyone’s welcome,” Jace continues, with Serena adding: “As long as you’re respectful.”

Or, as Serena aptly sums it up: “Come to DICS, don’t be a d**k”.

Drop In Care Space has been fundraising to cover rent through national campaign GiveOUT Day, which supports donations to LGBTQIA+ organisations, charities and groups. Tax-deductible donations are accepted via the Care Space website.

If this story raised issues for you, you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

If it is an emergency, call 000.