Cemeteries are nothing to fear, say two University of Adelaide researchers. In fact, they could be far better for our health than we realise.

What becomes of the dead?

Around the world, many curious pandemic behaviours have emerged. The seemingly innate and catastrophic fear of being caught short of toilet paper, for example, drew the confusion and ire of many.

A more macabre habit was the double-wrapping in plastic of the COVID deceased during burial (once around the body and again around the casket), as was recorded in Durban, South Africa.

According to reporting in January by South African news website Independent Online, the country’s Department of Health deemed the practice unnecessary and called for it to stop. This was backed by the World Health Organisation (WHO), which stated there’s no evidence the virus can be transmitted from dead bodies to the living.

Still, in troubling times morbid minds are wont to turn to morbid topics, so CityMag wondered what, if anything, we have to fear of the dead.

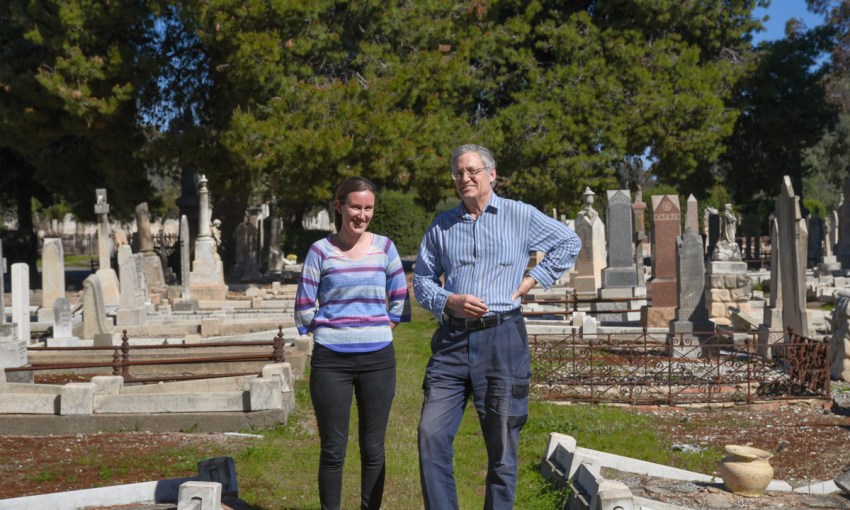

Our concerns were quickly allayed by University of Adelaide researchers Professor Philip Weinstein and Doctor Jessica Stanhope, who both study the impacts of the environment on human health.

Philip references two examples of burial sites causing potential negative health effects for humans.

One was a mass burial of anthrax-infected sheep that, due to soil erosion over time, became exposed; the other was stagnant water in vases providing an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes on Réunion Island during an outbreak of mosquito-borne disease.

But as for what nasties may be transmitted into the soil, Philip and Jessica reiterate that we have little to fear.

“We couldn’t find any evidence of infectious disease leaking from cemeteries into groundwater and then causing an outbreak of something… But yes, it is a theoretical possibility,” Philip says.

“But that’s also going to be reduced if the ecosystem is healthy, because that will regulate it anyway,” Jessica says. “So I guess the risk is going to be higher where those cemeteries aren’t particularly green and biodiverse, and the soil health isn’t great.”

To keep the soil healthy, our burial practices could be adapted to introduce fewer harmful chemicals into the ecosystem.

“[Natural burials] would be [more beneficial] because you’re not introducing the chemicals in there,” Jessica says. “But also just the fact they’ll break down faster if they’re not treated.”

West Terrace Cemetery features an array of looming greenery, some of which is influenced by the changing cemetery planting fashions of the last 184 years.

According to a digital self-guided nature trail compiled by the cemetery, the historical site is also “recognised as a valuable seed bank for the reintroduction of rare and endangered indigenous vegetation to the Adelaide plains”.

There are benefits to maintaining cemeteries as biodiverse greenspaces, and not only for the health of the landscape.

While many people are familiar with the concept of a gut microbiome – the ecosystem of bacteria and other microorganisms in your digestive system – there is a field of study emerging around the environmental microbiome and how it interacts with the microbiome living on and within us.

The assumptions being tested are whether greenspace exposure is linked to a range of positive effects, such as mental health, gut disorders, pain, inflammatory disease, allergies, asthma, autoimmune diseases and even supporting cancer care.

“We’re still, in a way, assuming that the environmental microbiota affect us, or affect our microbiome, so that’s going to be the growing area [of research],” Jessica says.

And you may not even need to physically step into the greenspace to receive the benefits.

“If you restore peri-urban greenspace, then the microbiome drift,” Philip says.

“Things like the Torrens Linear Park is brilliant from that point of view. People can use it as a transit corridor, and even if they don’t, it goes through the middle of the city and the microbiome that comes from that biodiverse environment is benefitting people who go nowhere near it.”

Our greater understanding of the environmental microbiome will only come with funding, though, and despite the broad array of benefits that could flow from better utilising our greenspaces, the research is difficult to sell.

“We’ve got an element of magic-bullet thinking: ‘I’ve got an infection, I’ve taken antibiotics, now it’s gone.’ Greenspace is not that,” Philip says.

“It’s sort of an indirect influence on multiple systems concurrently that don’t work for everyone. But at a population level, there’s no question it’s good for the population.”