After teaching himself to read and write, Adnyamathanha man Terrence Coulthard has compiled and recently published a dictionary and cultural guide of his people.

An Adnyamathanha dictionary, 40 years in the making

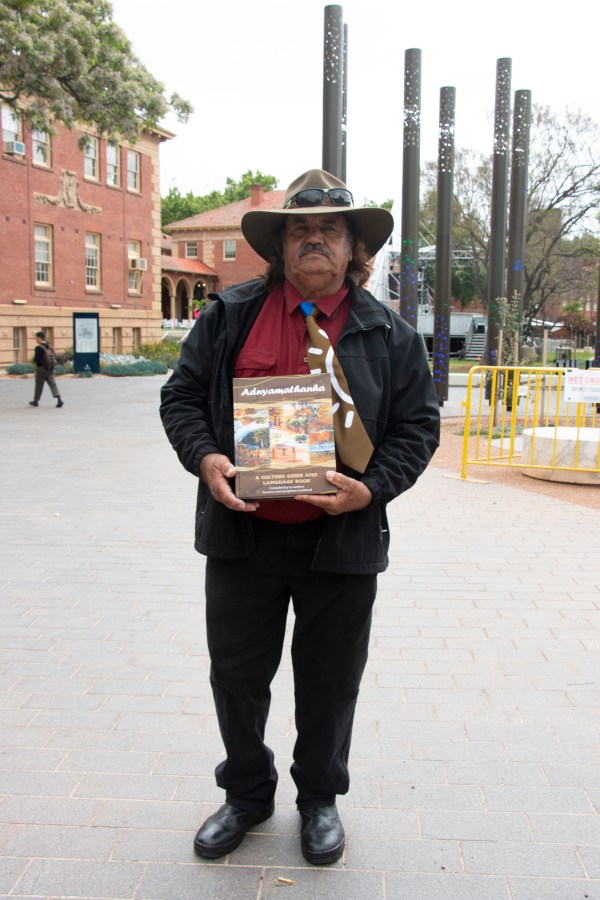

CityMag meets Terrence Coulthard hours before he’s due to launch the culmination of his life’s work, the Adnyamathanha Culture Guide and Language Book, at the University of Adelaide’s Kaurna Learning Circle.

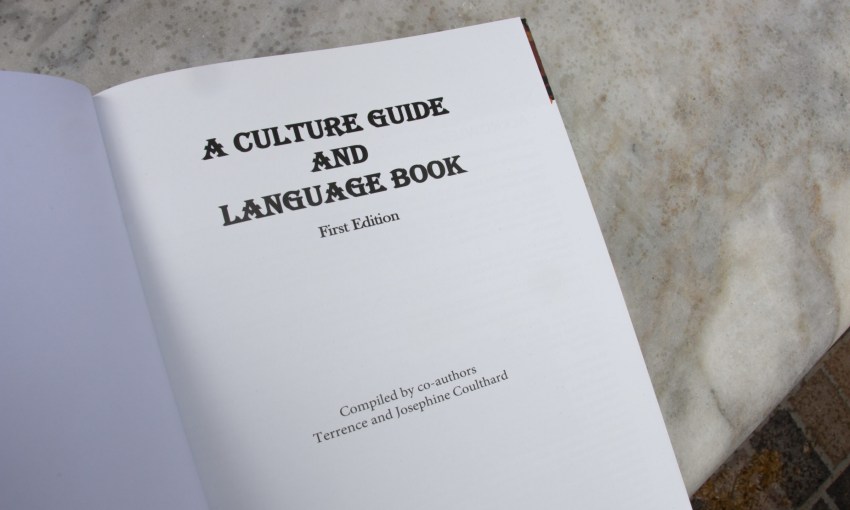

The Adnyamathanha Culture Guide and Language Book

Co-authored by Terrence and Josephine Coulthard with help from the Mobile Language Team.

Order the book online here.

UPDATE:

An earlier version of this story stated Terrence Coulthard’s book was the first Adnyamathanha dictionary. An earlier Adnyamathanha dictionary was published in 1992, compiled by John McEntee and Pearl McKenzie.

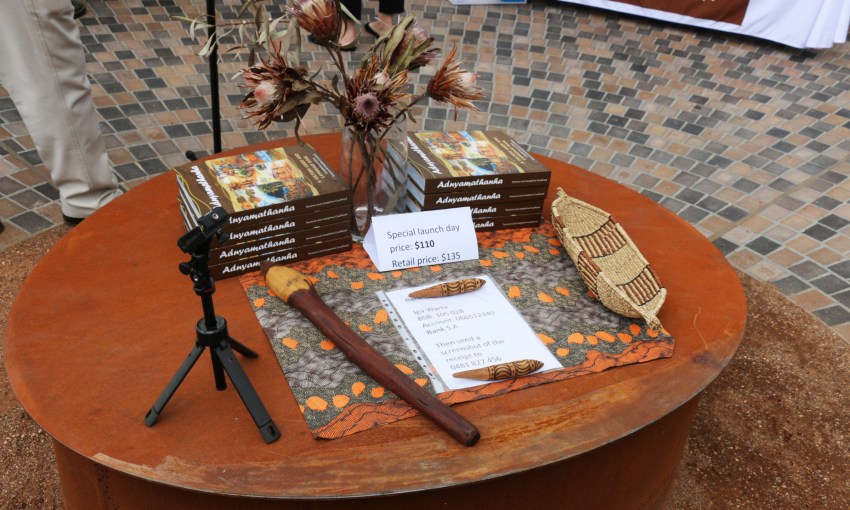

Terrence’s wife, Josephine Coulthard, sits behind a large desk piled high with the recently printed hard-cover books.

A group of their grandchildren, here to witness the launch of the book, talk quietly amongst themselves before the event kicks off.

Some of the youngest members of the Coulthard family have traveled as far as Port Augusta to be here, and they tell CityMag it’s bizarre seeing their grandparents’ work printed and published after all these years.

“For 40 years of my life, I’ve been collecting data,” Terrence tells us, “and sadly, a lot of the people that’s been a part of that process have since died.

“It’s now time for me to give this information to the next generation. Otherwise, if I die, I take it with me – that’s how serious it is.”

There are roughly 3,000 Adnyamathanha people spread between the northern Flinders Ranges and metropolitan Adelaide, Terrence says, but many have passed away, taking their knowledge with them.

To ensure their Yura Muda (stories and culture) endures, Terrence started documenting the language.

The result of his tireless work is a 450-paged book that includes translations, illustrations, photographs and stories of the Adnyamathanha people.

Terrence never trained to be a linguist. He grew up on the Nepabunna Mission in the Flinders Ranges and dropped out of school in year 8.

He entered the workforce only knowing a few numbers and letters, because, as Terrence explains, you don’t need to be literate to be a stockman.

But he was a fluent Adnyamathanha speaker, and still holds an enduring love for his culture and language.

“And I suppose I was hungry for it,” Terrence says.

“[Adnyamathanha language] just needed to be recorded, first of all, for my own purpose, and then it grew into a situation where I thought this could also benefit my family.”

Terrence and the Coulthard family run Iga Warta, a cultural tourism business located near Nepabunna and Mount Serle in the Gammon Ranges.

While running cultural and historical tours for Iga Warta, Terrance always carried a notebook in his pocket. This was in case he stumbled upon an Adnyamathanha word he didn’t have written down.

“When a person came along, [if] we would be having a coffee or something, they’ll say something in Adnyamathanha and I’ll make a note of it,” Terrence says.

“Then one other time, I’ll go and check them to see if I’ve got it. Nine times out of 10 I didn’t have it.”

In the 1970s, non-Indigenous linguist Bernhard Schebeck visited the Nepabunna region to record the Adnyamathanha language, and another academic Dorothy Tunbridge visited the area in the 1980s. In 1992, John McEntee, also a non-Indigenous linguist, and Pearl McKenzie, an Adnyamathanha woman, published the first Adnyamathanha dictionary.

Terrence’s work continues this legacy in keeping Adnyamathanha alive and accessible.

In the mid-’80s, when Terrence first started pulling his book together, he copied his notes from butcher paper to a typewriter. At the turn of the century, he then transferred them onto a computer.

Terrence approached the University of Adelaide’s Mobile Language Team two years ago to help get the book off the ground. Linguists Bea Fagan and Eleanor McCall helped Terrence to develop the document further and search for inconsistencies.

Despite the Adnyamathanha man devoting four decades of work to recording the words of his people, he doesn’t consider himself a linguist. He’s not trained like some of his colleagues, he says. But Terrence is proud of his work.

“As well as learning to read and write, and raising two kids, I was then enrolled in university to become… the first Adnyamathanha school teacher. But it wasn’t easy,” Terrence says.

“That whole team have been super in supporting me.”