Samira Elagoz's 'Cock Cock... Who's There?' is a personal exploration of gender relations and sexual violence. The artist spoke with CityMag about the process of creating the show and the many reactions it elicits from audiences.

Cock Cock… Who’s There? Q&A with creator Samira Elagoz

Six years ago, Finnish / Egyptian filmmaker Samira Elagoz was raped by her then-boyfriend.

Cock Cock… Who’s There?

28 February—3 March

Adelaide Festival

Main Theatre, AC Arts

39 Light Square, Adelaide 5000

Tickets

A year after the attack, Samira decided to use her ‘rape anniversary’ to conduct a series of filmed conversations which detail both her family and friends’ response to the assault. The experiment revealed well-intentioned, honest, and sometimes challenging attitudes toward gender relations and sexual violence.

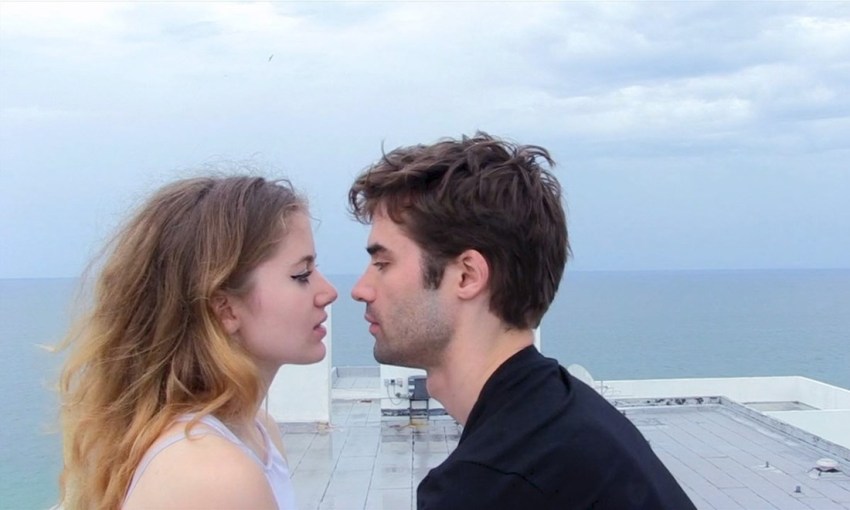

Across three years and three continents, Samira then initiated a series of interactions with strangers in their homes using Craigslist adverts and other online dating sites.

The culmination of this exploration is Cock Cock… Who’s There?, an unforgettable subversion of victimhood and a coolly powerful reclamation of self.

Ahead of Cock Cock… Who’s There?‘s run as part of Adelaide Festival, from 28 February—3 March, CityMag spoke with Samira about the show.

CityMag: How would you explain Cock Cock… Who’s There? to someone who hasn’t seen it?

Samira Elegoz: Split between screen and stage, the show turns my experience of rape into an observational documentary. I address misconceptions about rape victims, expose aspects of rape culture, and share my research of meeting men online.

Back in 2016 when I finished this work, there was no #metoo yet. Many rape stories I saw were about victimhood and how women were destroyed, never even alluding to the victim having any real agency. I was lacking any stories about the aftermath I could actually identify with, so I decided to share my own.

I was curious what the weird choreography of this stereotypical set up of ‘cis man meets cis woman’ is, and what the grey area is before crossing the boundaries. When does attraction transform into a desire and lust that could lead to domination, possession, or violence?

Work I had seen about rape was always some moralising quest or an attack on men. But I was of the firm belief that not vilifying them would allow those that recognise something of themselves to analyse rather than reject.

I very much wanted to make a performance about rape that would be accessible to men too.

What’s the most common question you get with your work?

With no doubt it is: “Weren’t you scared while filming these men?”

First of all, I did have safety regulations; it was not danger I was interested in capturing on film. And I’m sure any woman knows that you might potentially be in danger when alone with a man. So when removing that element of danger, I also don’t need to censor myself.

However, it’s still a pet peeve that I often get asked that question. As I’ve been to many film festivals and following my male colleagues, who went to wars with their cameras, I notice no one asked the same of them. It’s cute people are worried about me, but it cant help but feel patronising, victimising and basically questioning my ability to make decisions. As if I’m not in charge of my own body.

It’s also frustrating to live in a world where it is my responsibility to protect myself from men. Rape culture is exactly about creating that fear in us. Making women afraid to take part in public life. And this is not about ‘protecting’ women, but controlling them. I think, for me, it was more that I do recognise the risk, but I attempt to build a kind of social laboratory where I can safely poke, prod and experiment.

Samira Elagoz

What is the most common positive comment you get?

That I would be ‘brave.’ A statement I don’t really know what to make of.

But I find this text by Laurie Penny very relatable: “I am not brave. I simply know what to be scared of; I know to be scared of everything. There is freedom in that fear. That freedom makes it easier to appear fearless. I have been broken, so I am prepared should that happen again. I have, at times, put myself in dangerous situations. I have thought, ‘You have no idea what I can take’. Human endurance fascinates me, probably too much because more often than not, I think of life in terms of enduring instead of living.”

Once you have survived something traumatic you know there is no simple fix… Especially as you come to understand exactly what you have survived.

What’s the most negative comment you get?

For those that just can’t understand, or don’t identify with what I did after my rape, I am either lying or mental. Which is pretty dark. It was important and intriguing for me to expose the actions one might take after being raped, which still seems to be a bit taboo.

I wanted to convey not only how complex it can be to cope with rape, but that there are many ways to handle such trauma. Delving into the psychology of what it’s like to move through these various iterations of shock, anger, and healing, you find contradiction is a big part of trauma.

My work is often described with the phrase, “an unconventional way of dealing with trauma,” which is funny to me. I mean, what would we define as conventional anyway? Self harm? Celibacy?

I wanted exactly to make the audience re-think their views of what rape might mean to a victim. I wanted to illustrate this contradiction of being both a sexualised and sexual woman, which is most often presented as an either/or situation.

What’s the most depressing aspect of your work?

I get to see how behind people are in with their thinking. Touring with my rape performance for almost 3.5 years, I’ve heard so often, from journalists, strangers, acquaintances, peers from the scene and from different gender identities, that my rapes were my fault in a variety of misguided ways. That it’s just down to how I look or behave. That old tautological song sang to women of ‘Be modest and you won’t attract trouble.’

Rape seems to be one of those rare crimes where it is the victim that is on trial rather than the accused. And that same inclination of people is also true with my work. Sometimes I hear that because I seem ‘neutral’ on stage, it cannot have been rape, as if people expect victims to be performative.

At a Q&A in Israel, a man kept asking me, “Why aren’t you crying when you tell your story?” A sex crime lawyer came to talk to me after and explained this is a typical perspective in court as well – that the judge doesn’t believe a female victim if they are not showing signs of being completely broken.

It is common knowledge that detachment is an important and healthy part of the coping process. By the time most of the victims actually get to court, they’ve already been through all those emotions, to be expected to perform them to seem genuine is gross.

And what is most challenging about your work?

When putting my own life so strongly in the work it causes a lot of stress about people misunderstanding it. I can of course only give the parameters of my work, and leave them to interpret.

But it also makes people quite forward. They think as I have created a very personal work it means they can ask me equally personal questions. Detailed and intimate stuff that they should absolutely not be expecting an answer to.

The most irritating hypocrisy; the work about my experience of sexuality and rape has often been flagged with trigger warnings, age limits, even labelled shocking and explicit. Whereas I’ve seen some theatre plays directed by men, that have actual acted rape scenes on stage, with no warnings whatsoever. I mean complete with blood splatter and rough depiction. And then a girl speaks of sex and trigger warnings galore. Mind-boggling.

What have you been wanting to talk more about relating to your work?

My show talks about rape and dating. But dating after being raped is actually a real fucking deal to navigate. I think for too many of us it’s just easier to withdraw from the whole dating scene. Telling a potential ‘lover’ about your rape(s) can be, not just humiliating, but an almost retraumatising experience.

My instinct was always that it would eventually be more harmful to protect yourself by shying away from interaction. And when touring with my performance these past years, I have tried to be an advocate for victims who do still feel sexual. Some are even more so than before the trauma.

Victims of sexual violence don’t necessarily lose their sexuality, and as such shouldn’t have to feel fear or shame about it, but there is an almost imposed guilt about showing ourselves as sexual. What I haven’t really talked about is how to navigate the dating world after a rape. I’ve not read much elsewhere on the topic either.

I mean, it’s pretty much a gamble anyway, meeting someone compatible. Never mind having to confide in this person, or even tell them of disappointing restrictions, in the early stages of being intimate. Someone who you can’t really know is genuinely caring, or even interested beyond their sexual attraction.