The future of Australian housing is already here, and can be found in the form of a sustainable, hand-built home tucked away in the Adelaide Hills.

Home of the future: Earthship Ironbank

On a block of land up behind Stirling, Martin Freeney, over about eight years, worked alongside a plethora of volunteers, family, and friends to build a house of the future.

Learn more about the Earthship Ironbank or book to stay there through the website.

Founder of the earthships building movement, American architect Mike Reynolds, is touring Australia and will be giving a lecture in Adelaide on October 21. More details are available here, and tickets can be purchased here.

Modelled on the earthship structures devised by American architect Mike Reynolds, Martin’s home is off the electricity grid, highly energy-efficient, and operates solely on collected rainwater. It also contains an intensely pleasant greenhouse within the structure of the home, that not only grows food for consumption, but also provides a passive heating and cooling cycle.

Known as the Earthship Ironbank, the house is a package that – in its own small-scale way – addresses many of the world’s biggest problems.

“Today Tonight came out and did a story, and they were all about me being a prepper for the end of the world, for the zombie apocalypse,” says Martin.

“And I thought, I’m not a prepper, but actually – I am preparing. I’m preparing for climate change, I’m preparing for resource scarcity when costs of petrol, and energy, and water is all going through the roof.”

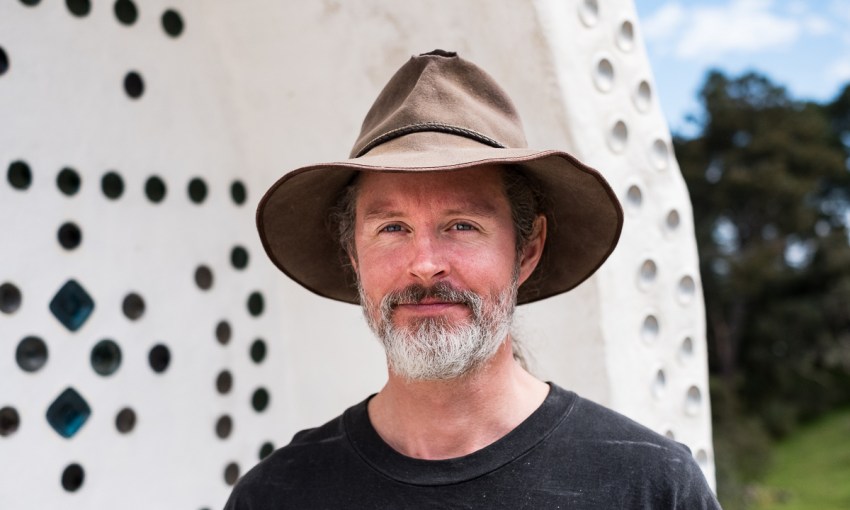

Martin Freeney: Not a prepper, but he is preparing. And grinning.

Unlike zombie apocalypses, the things Martin is preparing for are likely realities.

But despite that, the Australian housing industry is only slowly lumbering around to create residential buildings that cater to Australian conditions and modern environmental realities. Energy efficiency is increasingly becoming a priority, but there’s still little interest in water efficiency or use of lower-impact construction materials.

“I think every state has their way of doing their housing – partly to do with the climate but also partly to do with the history of how we’ve always done it,” says Martin.

“And how we’ve always done it in Australia is quick and dirty – hardly any insulation, drafty, poorly sealed up buildings, even now we’re only just starting to say, ‘there’s this stuff called double glazing, maybe we should use it’.”

The Earthship Ironbank is the opposite of quick and dirty. Much of its design is based upon the results of Martin’s PhD, for which he travelled to visit a large community of earthships in Taos, New Mexico. There, he studied their designs –considering how they compared to each other, and to more conventional housing, in the realms of thermal performance and environmental impact.

The outcome of Martin’s research (apart from a PhD) is this little home made from highly insulative materials like tyres packed with earth, bottle bricks, beer cans, and more conventional materials like cement mortar, glass, steel, and wood.

Bottle bricks form part of the earthship’s walls

The internal greenhouse provides a thermal buffer between the outside conditions and the living area, while two tubes that draw air into the home after running it underground to cool act as a natural, power-free version of air conditioning in the Summer.

A solar system on the roof coupled with a battery inside collects and stores all the electricity needed for the low-consumption home, which can be connected to mains power in an emergency. Adaptations like a roof sprinkler system were added specifically for Australian conditions, to help the home be bushfire ready.

Not all earthships have alpacas. But perhaps they should.

While this particular home took years to build over weekends and holidays here and there, Martin says it could be done in 6-9 months and for about the same cost as a conventional home if somebody was dedicated full-time to the cause.

But even while time and cost are not vastly different to standard construction, earthships aren’t gaining rapid momentum as a housing style.

“So I think most people just say, you’ll never get [Council] approval for that,” says Martin. “So there’s certainly a cultural and societal paranoia that you can’t try something different.

“This was the first Council-approved earthship in Australia. I actually really didn’t have to do anything strange or unusual to get approval.”

The other challenge is the number of people who are generally involved in an earthship build, which requires a vast amount of (wo)manpower to do things like belt earth into compact form for walls. But, actually Martin sees this as an advantage.

“I’d say 95 per cent of all earthships have been built in that collaborative way,” says Martin. “At one stage we had 35 people camped down the bottle of the hill for five weeks one summer.

“And that’s a thing that I think a lot of people probably fail to understand is that there’s actually a really enjoyable process…. Everyone has come to learn and meet other like-minded souls, it is a social gathering in that way.”

And all those who volunteered in building this earthship now have some of the knowledge needed to build their own, so little by little, person by person, these homes could become much more a part of Australia’s future.

Come in