University of Adelaide PhD student Ishka Bless is cataloguing the flavour profiles of edible insects to offer chefs, cooks and general consumers a guide to adding bugs to restaurant menus and daily meals.

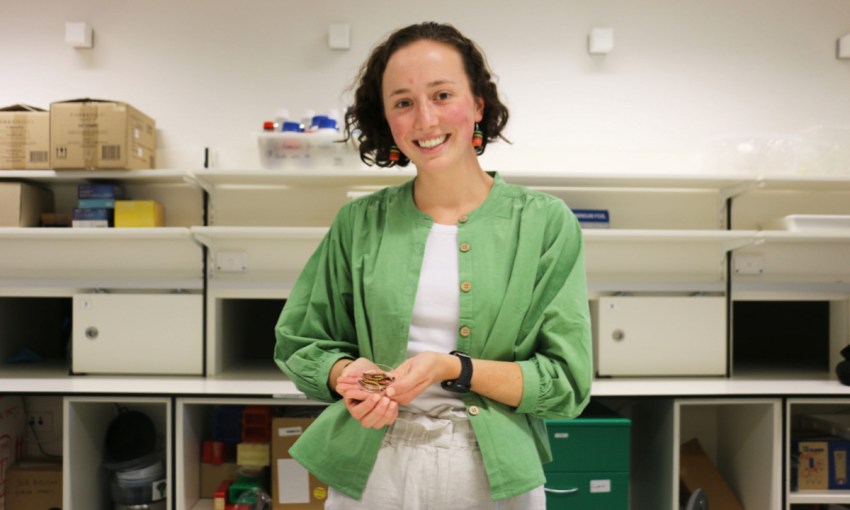

Ishka Bless wants to see more insects in Adelaide restaurants

Ishka Bless’ favourite edible insect is the king mealworm – the Don of the worm world.

Before a king mealworm evolves into a darkling beetle, they’re fat, long larvae with a distinctly meaty flavour. Pop one dried morsel into your mouth and you could easily mistake it for a prawn – or bacon.

“It kind of reminds me of fish, and it’s almost nutty,” Ishka, a University of Adelaide and University of Nottingham PhD student, tells CityMag from within a food lab in Waite.

“I found out recently that one of the flavour notes is bacon, and I don’t eat bacon and I realised on reflection that that’s what it was.”

Ishka meets us wearing a smart green blazer, and not the cliché white lab coat we were expecting. She is an avid consumer of bugs, and also has a hunger to make entomophagy (the eating of bugs) mainstream.

Through her research, which will be conducted over seven weeks from March to April, Ishka will catalogue the flavours people experience when they consume a dried worm or cricket. She will train a team of volunteers to talk about the notes and textures of the insects they’re eating, and grade them.

From this information, Ishka will develop a flavour wheel outlining the sensory experience of the bugs: flavour, smell and texture. She will make this flavour wheel available to the hospitality industry, so chefs, cooks and restaurateurs can envisage how the insects can be incorporated into their menus.

New here? Sign up to receive the latest happenings from around our city, sent every Thursday afternoon.

Even with this information, once massive hurdle to the uptake of insects as ingredients remains: a gap in Western knowledge.

More than two million people worldwide eat bugs, particularly in Asia and Africa. They’re an excellent source of protein, and can be farmed with minimal space and resources. Locally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are also no stranger the food source. But the West has no idea what do to with insects. This is a problem, Ishka says.

“We don’t really know how to eat them,” she explains.

“If you’re given a new ingredient and told that it’s an ingredient, and you’ve never experienced before, there’s a bit of fear around that. That’s a fact.

“Insects in general have been eaten for thousands of years, and they’ve actually played an important role historically in human diets. But with many Western countries, they have almost disappeared from our diet in the last few hundred years.

“That means that as Western consumers, we’re less familiar, quite often, with the concept of eating insects, so we haven’t eaten them ourselves.”

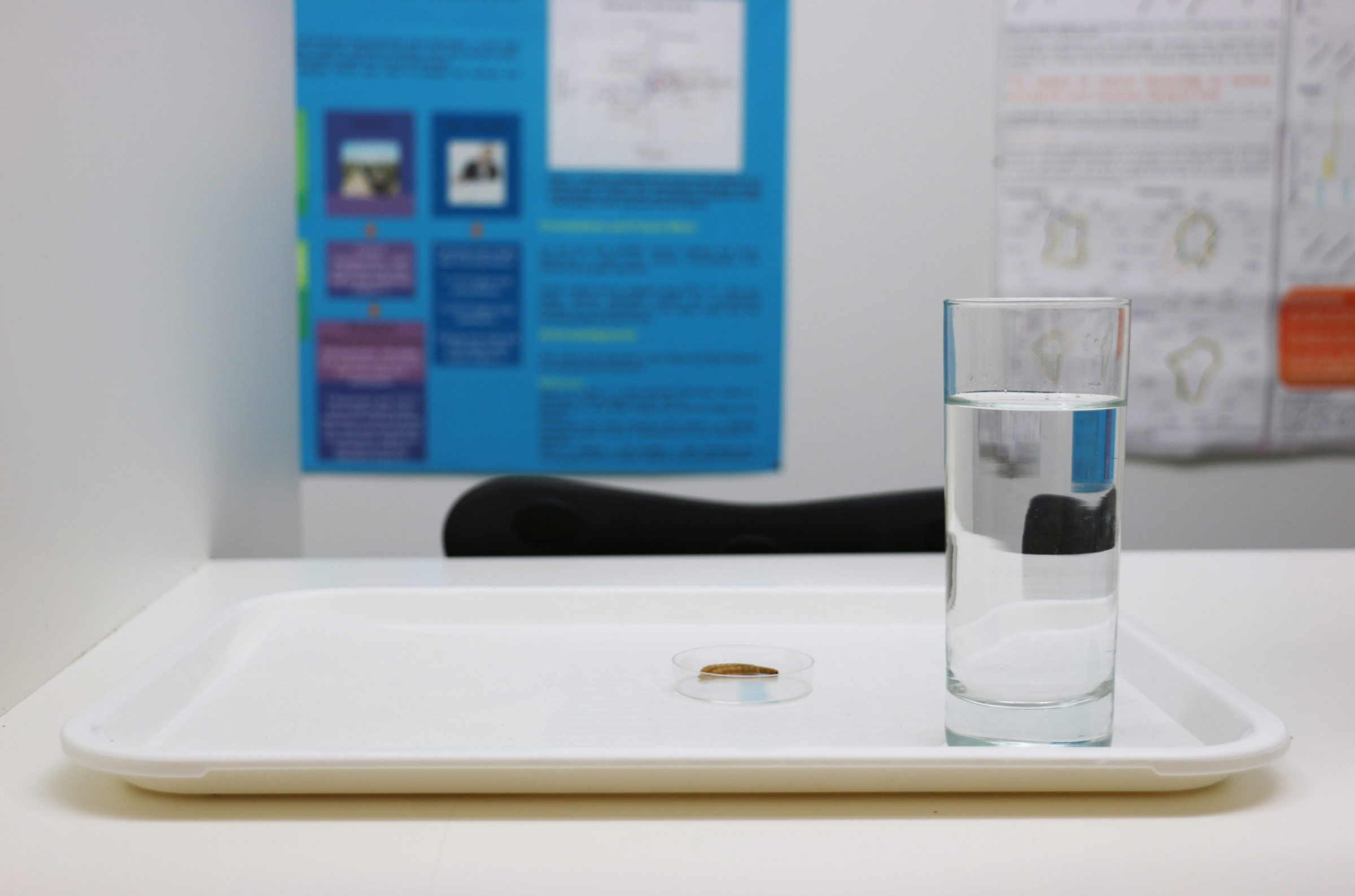

A platter the insect graders can expect to experience

Another issue is preparing them properly. Crickets, like most insects, are best enjoyed roasted. It brings out the nutty and “prawny” flavours, Ishka says. It makes them more like prawn crackers.

According to Ishka’s PhD supervisor, University of Adelaide agriculture, food and wine professor Kerry Wilkinson, roasting removes the “squish” sensation, which is the ick factor that often puts people off.

As the gap between creepy crawlies and cuisine has widened, we’ve become accustomed to seeing bugs as foreign entities to our dinner plates. Despite internationally renowned restaurants like NOMA introducing ingredients like ants to their meals, eating bugs is still seen as avant-garde.

“They’re also not available in our local shops,” Ishka says.

“That means that we’re less familiar with the concept, or maybe a little less comfortable, because of the fact that when we see insects, we see them and we don’t associate them as food.

“Straight away, when we see them on a plate, we think, ‘Oh, I’m not quite comfortable with that’. It gives a sense of disgust, and that sense of disgust is one of the big factors that we think is behind the lack of consumer acceptance.”

For Ishka, this is not just an academic pursuit. She puts her belief in the revolutionary potential of bugs where her mouth is.

The researcher adds cricket powder to her morning muesli and adds dollops of dried king mealworms on her dinner. She’s also performing incidental advocacy through exposing her housemates to eating insects.

“The day [one housemate] moved in, I moved my mealworms in, so she learned to become comfortable quite quickly,” Ishka laughs.

Can you hear the crunch?