Speaking with CityMag, Cheryl Axleby discusses the negative impacts of state policies supposedly designed to protect Indigenous South Australians, and what changes she wants to see during her tenure with the ALRM.

In conversation with Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement CEO Cheryl Axleby

Thousands marched and chanted in Tarntanyangga Victoria Square almost two months ago, in a protest sparked by the senseless killing of George Floyd, a Black American man, at the hands of four Minneapolis police officers.

South Australians gathered to protest the killing, and the undue force regularly used by police forces against minority communities, whilst simultaneously protesting our country’s own heavy-handed policing of minority communities, in particular First Nations people.

Australia has seen more than 400 Indigenous deaths in custody since the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, none of which has led to a single conviction of any person involved.

This number includes 10 deaths in custody in South Australia since 2008, as charted by the Guardian.

Cheryl Axleby. This picture: Supplied

Engaging with the issue through protest and communicating with state and federal political representatives about your concerns is an excellent start, but understanding how the law affects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in our community is imperative.

If we are able to articulate exactly what these problems are, how they are relevant to the community we live in, this is when change can happen.

Or, as proud Narrunga woman and CEO of the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement (ALRM) Cheryl Axleby puts it, change happens when conversations occur.

This conversation must include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The ALRM is a community-controlled organisation providing pro-bono legal services for Indigenous people in South Australia on civil and criminal matters.

For the last eight years, it’s been headed-up by Cheryl, whose 35-year career is largely rooted in not-for-profit sectors, advocating on law and justice, Indigenous and women’s issues.

CityMag sat down with Cheryl to discuss why the ALRM is so important to South Australia’s First Nations people, and how she hopes the organisation might shape our state’s future.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following article contains images of people who have died.

CM: How did ALRM come about?

CA: ALRM was established in 1972 through a grassroots movement, where concerned Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders came together seeking to develop specific Aboriginal legal services because of how our people were treated before the law.

CM: How were First Nations people treated back then?

CA: There was a lot of racism prevalent in the ‘70s. But in regards to the system itself, there was a lot of what we would call serious police brutality.

We advocated for land rights, so getting land rights for our people, and civil rights in regards to discrimination. That meant people could actually take up matters when they were being discriminated against in a legal context.

That law didn’t come into effect until 1975, but demonstrates we’ve advocated for positive change in law. Having fairness and representation before the justice system is two of the main things we still do today.

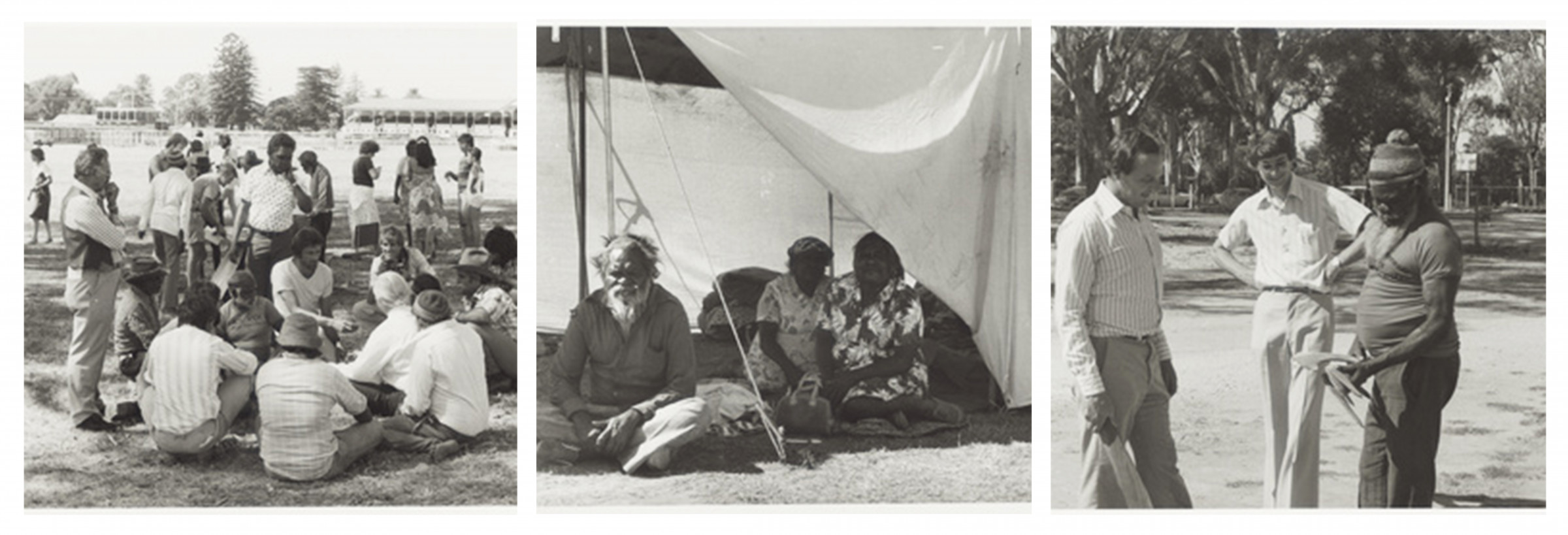

In 1980 the Pitjantjatjara Council of Elders travelled to Adelaide and camped at Pakapakanthi Victoria Park in protest of the State Government’s decision to open part of their land to mineral exploration. Pictures: State Library of South Australia

CM: What does ALRM do more broadly?

CA: We sit on committees and try and create positive change for Aboriginal people within systems. We also liaise with governments and key stakeholders, such as the Department for Correctional Services, South Australia Police and the Attorney General’s Department. We explain what happens when politicians are hard on law and order and how it impacts Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We also talk about the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people in the justice system.

For example, nationwide, a lot of people are held in custody without having their matters determined because they can’t get bail because of restrictive bail laws. And yet, what we find down the track is that they’re doing longer sentences – by being held in remand – for an offence. They are then sometimes found not guilty or may have had their charges withdrawn.

CM: You mentioned the bail system disproportionately affects Aboriginal Australians, what other laws affect these communities in South Australia?

CA: South Australia holds about 33 per cent of the nationwide figure of Aboriginal children being removed from their families.

A couple of years ago there were changes to the Child Protection Act, as a result of a Royal Commission into Child Protection in South Australia, but there has been a reduction to the Aboriginal [and Torres Strait Islander Child] Placement Principle, which emerged from the [1997] Stolen Children’s Generation Bringing them home report.

It’s been strongly recommended that every effort is made by government child protection agencies to maintain the cultural identity of an Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander child, and to look at where a child could be best placed within the community, whether that be through extended families or Aboriginal carers. That doesn’t happen anymore.

InDaily recently investigated the SA Child Protection Department’s ‘unnecessarily cruel and opaque’ practice of removing ‘at-risk’ Aboriginal babies from their mothers in Adelaide hospitals. Read the article here.

This picture: Dimitra Koriozos

CM: Why doesn’t that happen anymore?

CA: The department stopped it. Aboriginal child-rearing practices are a bit different to mainstream family practices. That’s not a negative. We see it as strengthening and a way to build responsibility, but that’s not considered.

That’s a real cause of concern because ALRM feels there could be a lot more engagement done with Aboriginal communities. Instead, there’s a lot of government-driven workshops, where the community are not invited to the table.

CM: How could things be done differently?

CA: By involving families when decisions are made on child protection issues. We have risk-averse policies and practices… so that governments better protect themselves, rather than looking at, how do we actually provide the best quality of care?

There are some of what I call discriminatory practices. If you’re an Aboriginal child and your family was in the system, then you’re automatically flagged. That’s discriminatory because there are some children and some adults who have come through systems, even their siblings, with great positive change. That’s not considered.

CM: How does racism influence policy?

CA: It’s not racism. There’s a one-size-fits-all approach, but we’re not all one people. We don’t speak the same language; we have different dialects; we have different customs. We also have politicians who have no idea, or [don’t] have anything to do with Aboriginal people in the first instance, that develop laws and don’t understand the cultural significance.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples also have other laws subjected and imposed. The cashless debit card was first implemented in predominately Aboriginal communities. Another example is work for the dole. Everyone is doing that now, but Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had that imposed on them for at least 30 years.

It’s those sorts of things, when we talk about policies and practices, that are imposed on our communities which are different from mainstream Australia.

CM: What did you see when the Black Lives Matter protest came through Adelaide?

CA: There were rallies like that in the ‘60s and ‘70s regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. But this US Black Lives Matter campaign threw a spotlight on Australia, which had 434 Aboriginal deaths in custody since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. (This number has since risen.)

There are deaths in custody because of health issues. There are deaths in custody because of self-harm issues, but there have also been some very questionable Aboriginal deaths in custody never properly investigated.

Then we have a coronial inquest, which produces recommendations about how things may be improved and [brought] in line with the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. But there were 339 recommendations that have not been fully implemented from that report. I know in South Australia quite a few haven’t been.

So, we have all these reports… which have reiterated a lot of the commonalities of the Royal Commission, which yet have not been fully implemented in Australia. People now want to see justice happen more than before.

This picture: Tim Lyons

CM: Will justice occur?

CA: We’ve had three more deaths in custody [nationally] since those rallies occurred. Today, we still have not had anyone held accountable. Justice has not happened and it won’t happen until we put pressure on politicians to start removing the immunity for police officers and prison officers. They should be subject to the same rules of criminal law as anybody else. That’s what’s happening in America, where you’re seeing police officers being charged with murder.

In South Australia, police investigate police and correctional services facilities still investigate their own. If we’re serious about transparency and want to address these issues, they should be treated like everybody else before the law.

CM: How have you been treated by the law as an Indigenous woman?

CA: I’ve never been in trouble (laughs). But as an Aboriginal person while shopping, I’ve been followed. As a young woman, with my family and cousins, I’ve been refused entry in pubs and hotels. This discrimination experience continues today. There is also discrimination in employment and private rental housing opportunities.

A lot of Aboriginal people struggle to get private rental because they’re refused the lease opportunities, which is why public housing was introduced and is significant. Some people think that Aboriginal people get special treatment. I can tell you that does not happen.

CM: What changes would you like to see before you retire?

CA: A dramatic reduction of our over-representation in the justice system and the removal rates of our children. But ideally, I’d like to see Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people recognised in the South Australian constitution, and government working effectively with Aboriginal communities.

I’d like to see Aboriginal people actually recognised at the table in Parliament. Not because we’re pushing our way [in] and saying ‘We need to be there’, but because we’re finally included.

CM: What will ALRM do going forward?

CA: We try and create opportunities for Indigenous peoples’ rights to be properly recognised. We also advocate to change laws that impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We also internally educate and create awareness of First Nations issues. We will continue to do that as an Aboriginal legal service.