Before Vicki Thompson was placed with her permanent foster family at age four, she didn’t know what a birthday or Christmas was. Now a foster carer herself, she explains why there is more to being a family than sharing a last name.

Fostering love

There was a clear and defining moment in Vicki Thompson’s life where she remembers understanding the full ferocity of familial love.

“I will remember this memory forever,” says the mother of nine (six biological and three foster children) at her metropolitan Adelaide home.

“One day my uncle made a comment to my [foster] mum saying, ‘These aren’t your kids’. She kicked him out of the house and was like, ‘Get out and don’t ever come back’.

“That was the turning point where I felt my mum and dad just loved us. We weren’t seen as anyone else’s children – we were their children.”

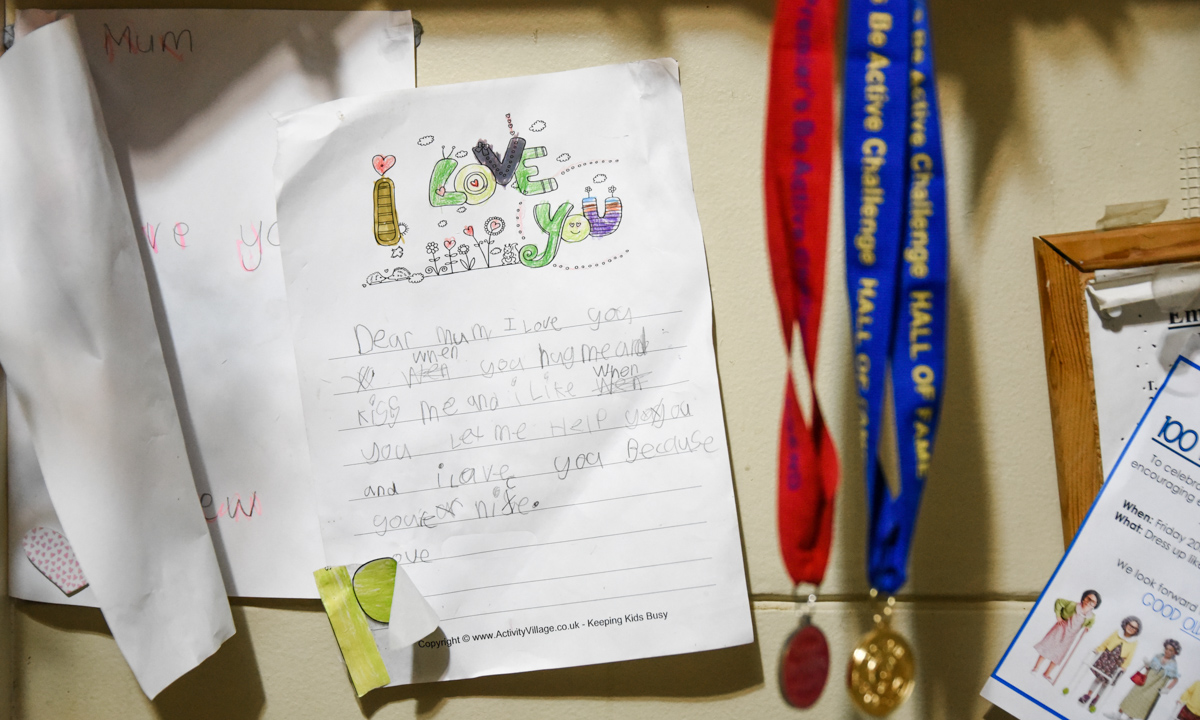

Inside Vicki’s kitchen, every surface is filled with artefacts from her kids. Crayon drawings cover the walls, and there are shelves lined with almost two dozen shining trophies.

Like any house occupied by a gang of highly energetic children, there are mountains of socks heaped in a corner near dropped school bags, and there’s a never-ending supply of cereal boxes stacked next to piles of homework. It’s messy, but it works.

Artefacts from a household filled with love

Vicki, too, overflows with love. As many times as we try to speak about her experience as a foster kid, with a flick of her purple hair, she’ll lasso the conversation back to her brood.

“My mum is still an active foster parent, and I think it was because of her that I felt like this was the right thing for our family,” she says.

“I wanted to do something with value to my life, and wanted to give somebody the opportunity my mum gave me.”

—Vicki Thompson

Vicki was delivered on the doorstep of her parents’ Crystal Brook property two days before her fourth birthday. As a kid, she remembers her dad taking her on bike rides, “smashing into the fence 1000 times”, and feeding the chickens and geese.

She had a “good childhood”, but bullies at school treated her terribly. Being a foster kid made her a target, and she tearfully recalls a time when her ponytail was tied to a bus rail.

Vicki is determined not to let this happen to her foster children.

“I want them to be absolutely strong in being proud of who they are,” she says.

Having come from a troubled upbringing with her biological family, Vicki also understands what life is like for the kids she’s taking in.

Before finding her foster family, she had no concept of birthdays or Christmas. “From that day with my new family, my life literally began,” she says.

Vicki, an Aboriginal woman with no further knowledge of her heritage, and her truck-driving husband, Wayne Wilson, signed-up as foster parents in 2017, through the state’s foster care service for Aboriginal children, Aboriginal Family Support Services.

Imperfection is ok

The couple have fostered around 10 kids, some short-term, some long-term. Over the years, they’ve learned some tough lessons. One of the most challenging is accepting they can’t fix everything.

“It’s really been a big learning curve for us to just step back, look at what needs to be done, and then focus on those individual needs,” she says.

This story first appeared in CityMag’s 2022 festival edition.

Through her experience growing up in a foster family, and in creating one of her own, Vicki knows there are many more important factors to creating a loving home than sharing a biological link.

“One of our kids only ever wanted a family. They’ve said, to this day, ‘I’m so lucky to have a family’. It’s like, ‘No, we’re lucky. We’re lucky we’re a family’,” she says.

“Through thick and thin, I would never hand them back.”