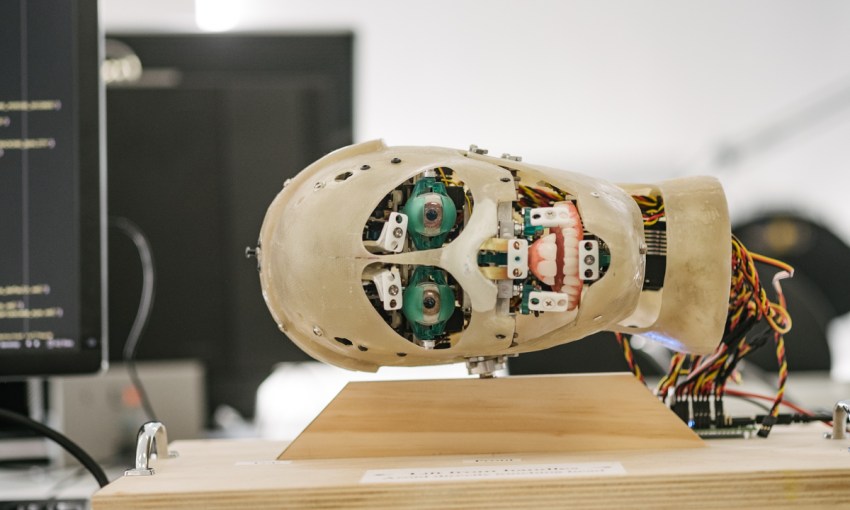

One of the first projects of new institution MOD unpacks the idea of what it means to be human through the medium of an unnervingly realistic robot head.

Building something beyond human

“I never know what to call him… umm, it,” says Penny Stevens.

Penny is a project manager at Sandpit – an Adelaide-based design and technology firm – and is used to working on curious briefs. But the one she is describing eclipses even her normal standard of weird.

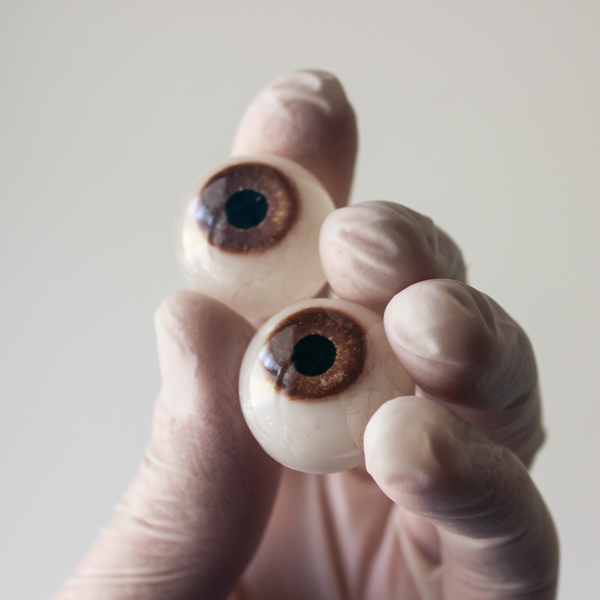

The strangely realistic eyeballs are connected to the…

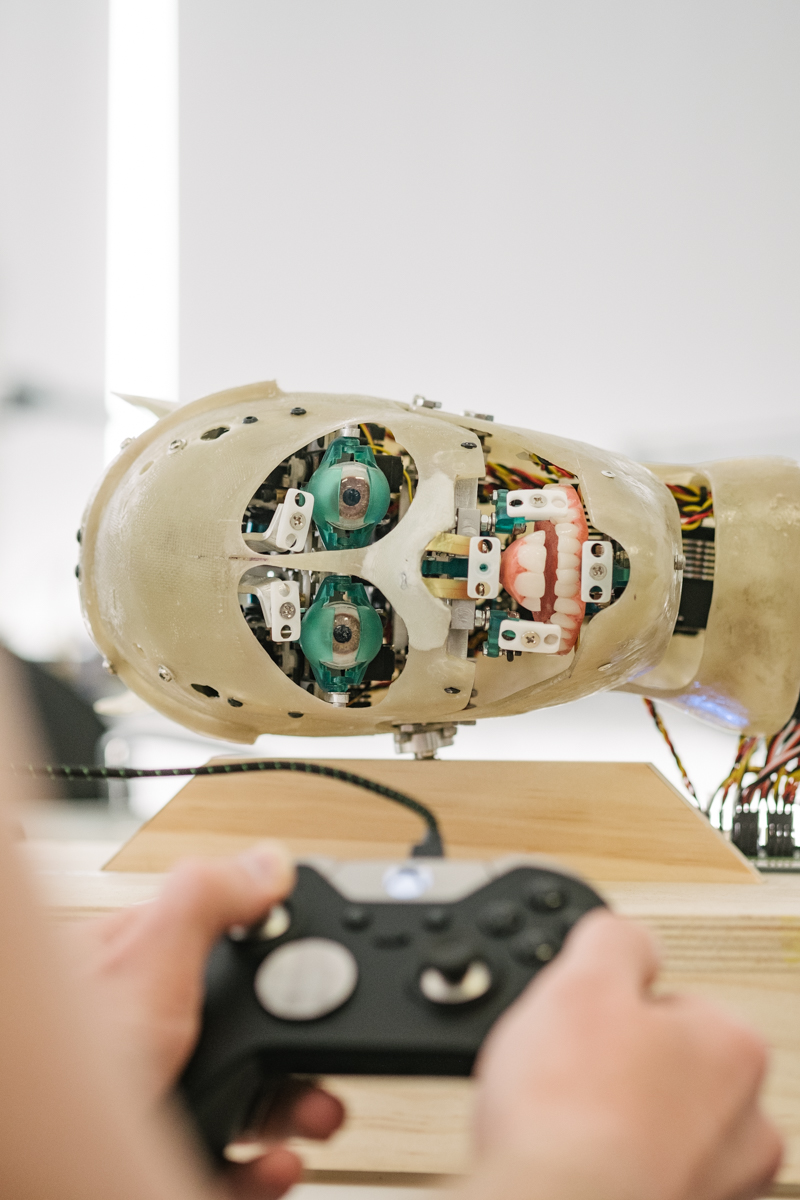

…off-putting, fleshy tongue and teeth (via several face plates)

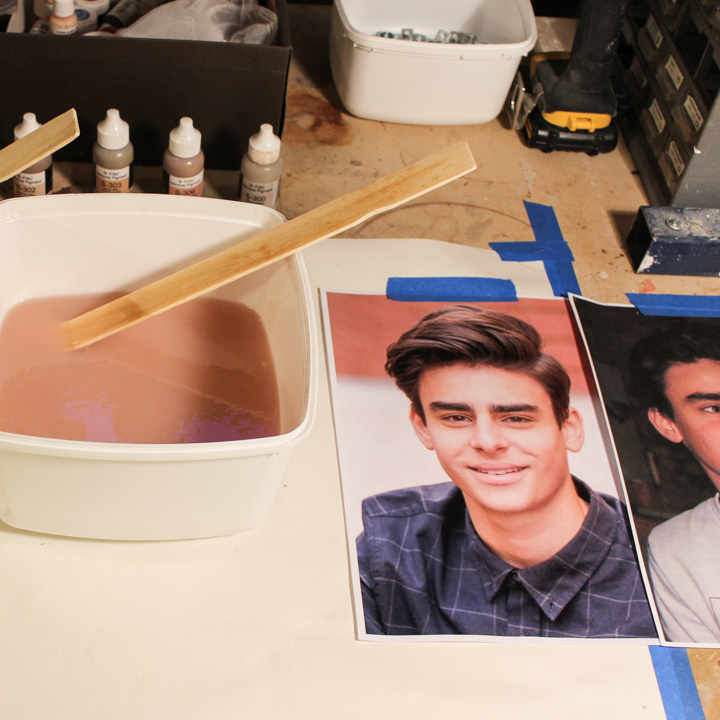

Skin tones (mixed by Marshall) are connected to the…

…face flesh (that feels creepily realistic)

“I think because it is so closely based on a human, you begin to humanise it with your actions and language,” she continues.

“It” is a robot head known as Josh, which has been designed and built in collaboration between Sandpit and rapidly-rising freelance prop and animatronic expert Marshall Tearle.

The idea for Josh, though, comes from the soon-to-open Museum of Discovery (MOD) at UniSA – an institution billed as examining ideas at the intersection of science, art, and innovation.

MOD’s digital exhibitions manager, Simon Loffler, dreamed up the concept of constructing and installing an animatronic head while considering the best way to explore the increasingly blurry line that sits between humans and robots.

“We’ve killed off dozens of ideas so it’s nice this one has stayed strong,” says Simon.

“This concept was to build an animatronic head that you can kind of have conversations with, and give people a feel for what that would be like.”

Simon took the decision to make the robot as realistic as possible – placing it firmly alongside robots that induce unease with the depth of their familiarity.

“We wanted to make it as generic as possible… so it’s more about the ideas the installation is exploring than who it is.”

Simon recruited Marshall to work on the project, and together they set about finding a generic human on which to model the prototype.

Adelaide teenager Yazeed Daher was chosen, and within weeks he found himself in Marshall’s studio, his head encased in silicone.

“It’s a pretty full on process,” says Marshall. “He’s got reliefs on him and his hair is all covered. We then cover him in a skin-safe silicone which is, in turn, covered in a plaster bandage.”

Marshall’s role in the process is enormous – he produces the entirety of the physical head, from its life-like skin, lips, eyes, tongue and teeth (that he builds and paints) to the mechanical innards that are used to animate the head.

Marshall says the greatest challenges have been finding room in the head to fit all the required mechanisms and working out how to position the motors around its mouth to create realistic movement as it speaks.

Even the eyeballs took hours upon hours to manufacture.

“The core of the eye is a separate part to the lens, so it roughly replicates how our eyes actually are,” says Marshall.

“They get air brushed and hand painted and also if you look closely, there’s little fibres in there that replicate the blood vessels. It’s kind of a daunting process – the last process of doing the lens, you can mess it up. I actually made five eyes to get those two.”

If Marshall is Josh’s body, then Sandpit is its brain. The firm is writing the code that powers Josh’s behavior – programming in things like a waking response that will be triggered by someone walking into the room in which the head is housed.

In deciding how Josh’s face will move in response to those around it, Sandpit are building a kind of personality into the robot – which will speak a limited range of phrases based on recordings they’ve made of Yazeed’s voice.

The process, says Penny, has involved far more subtlety than they initially imagined.

MOD is slated to open in May and will be located at 55 North Terrace, Adelaide.

“It’s amazing when you realise how much a small movement of your face can communicate,” she says.

When MOD opens in May, Josh will be on display – so it’s only a few months until anyone who walks through the door can experience exactly what a small movement of a hyper-realistic robot’s face can conjure for them.

This picture also by Tyrone Ormsby